The prom would be perfect, the protesters decided.

Their audience would be there; the majority of faculty and students from the IU’s Department of Theatre, Drama, and Contemporary Dance would be in attendance at the 2018 Drama Prom, the annual end-of-year departmental scholarship award banquet in the Tudor Room of the Indiana Memorial Union. Everyone would have to listen.

The day of, one of the nine student actors backed out during practice. It was too risky, especially when the protest would be aimed at the people controlling casting.

Before the awards ceremony, two of them pretended to be emcees and walked to the podium to begin while the rest waited in their seats in the audience, waiting for their cue. A false introduction later, the seated protesters started to speak while rising from their seats.

"I support the right of every student to an equal education,” one said as they stood.

“I know we can do better,” another said as she rose. “Because every community can do better."

As they stood, they walked toward the podium. They continued:

“I experience discrimination.”

“Men in this department have always tried to control my body.”

“I don’t see myself onstage.”

Woos and spoken-word poetry snaps of support came from some audience members, but many simply stared as they continued. Some laughed.

“This is our house, our shared house,” actress and black woman Adrianne Embry said in the piece. “And what happens to each of us in our house happens to us all.”

Sarah Zygmuntowski

In April 2018, a group of IU theater students staged a protest at the end of year banquet for the Department of Theatre, Drama, and Contemporary Dance.

***

The protest’s model came out of a movement in Chicago theater called #NotInOurHouse, which was created to address sexual harassment and abuse in the industry. The IU version was called “Not in Our Haus,” a reference to one of the season’s productions, and was expanded to include more student concerns — race chief among them.

Some students in IU’s department say the department has mishandled issues of race and gender and deprived them of equal educational opportunities, but a recent push toward a more progressive approach through casting, production details and independent student projects is trying to correct that.

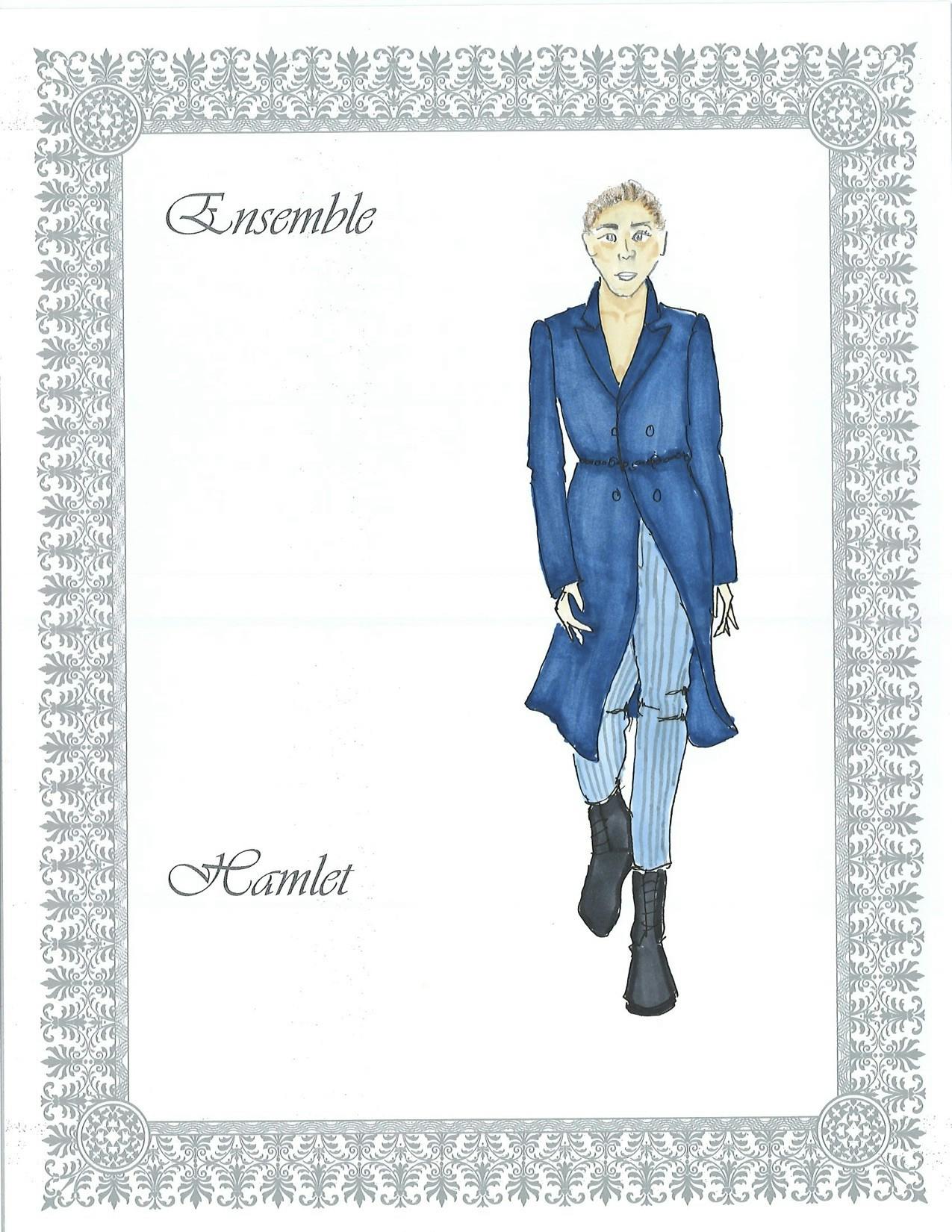

IU Theatre’s selected shows tend to be ones that traditionally let white men shine, such as this season’s “Hamlet” and other classic Shakespeare productions, or 2017’s “Peter and the Starcatcher,” which featured 17 roles for men and only one role for a woman.

Elle Kreamer

The cast of “Hamlet” stands on stage Dec. 3 during the first act in Ruth N. Halls Theatre. Director Jonathan Michaelsen cast more females than males for this production of “Hamlet.”

Students of color have had limited options for meaningful stage roles, frequently cast as ensemble members or roles with few lines. Plays with more than one person of color, such as last fall’s “Barbecue,” give students the opportunity to tell stories not focused on the white experience. But they’re outnumbered by more traditional choices, such as this fall’s production of “Hamlet.”

Considerations for the play selection process include the university’s Themester and the needs of actors in the graduate program. IU’s productions are chosen through a committee composed of faculty members and two students from the department’s Student Advisory Board, who consider proposed plays and eventually carve the list down to the season’s shows.

These considerations, some students say, have left them behind.

“I came in here completely blindsided. I didn't know I was going to be a token."

-Adrianne Embry, senior pursuing a B.A. in Theatre

***

Room A200 of the Lee Norvelle Theatre and Drama Center looks more like a high school gym than a Danish castle, with its wooden panel floors, tape demarcations of marks and imaginary coffins.

When “Hamlet” finally makes it to its destined stage in the Ruth N. Halls Theatre in December, the set is complex and evokes the disjointed mood that director Jonathan Michaelsen is aiming for. But for rehearsals, a rectangle of four tables with mismatched chairs was enough to be the Danish royal castle, Elsinore.

While the original play only has two women characters, this production’s cast has more women than men. For the purpose of this production, these originally male roles have been gender-swapped to fit the actors, such as M.F.A actor Glynnis Kunkel-Ruiz playing Horatio and associate professor Nancy Lipschultz playing Polonius.

Elle Kreamer

Actors Michael Bayler and Glynnis Kunkel-Ruiz perform a scene Dec. 3 during dress rehearsal at Ruth N. Halls Theatre. Kunkel-Ruiz portrayed Horatio, a traditionally male character, as androgynous.

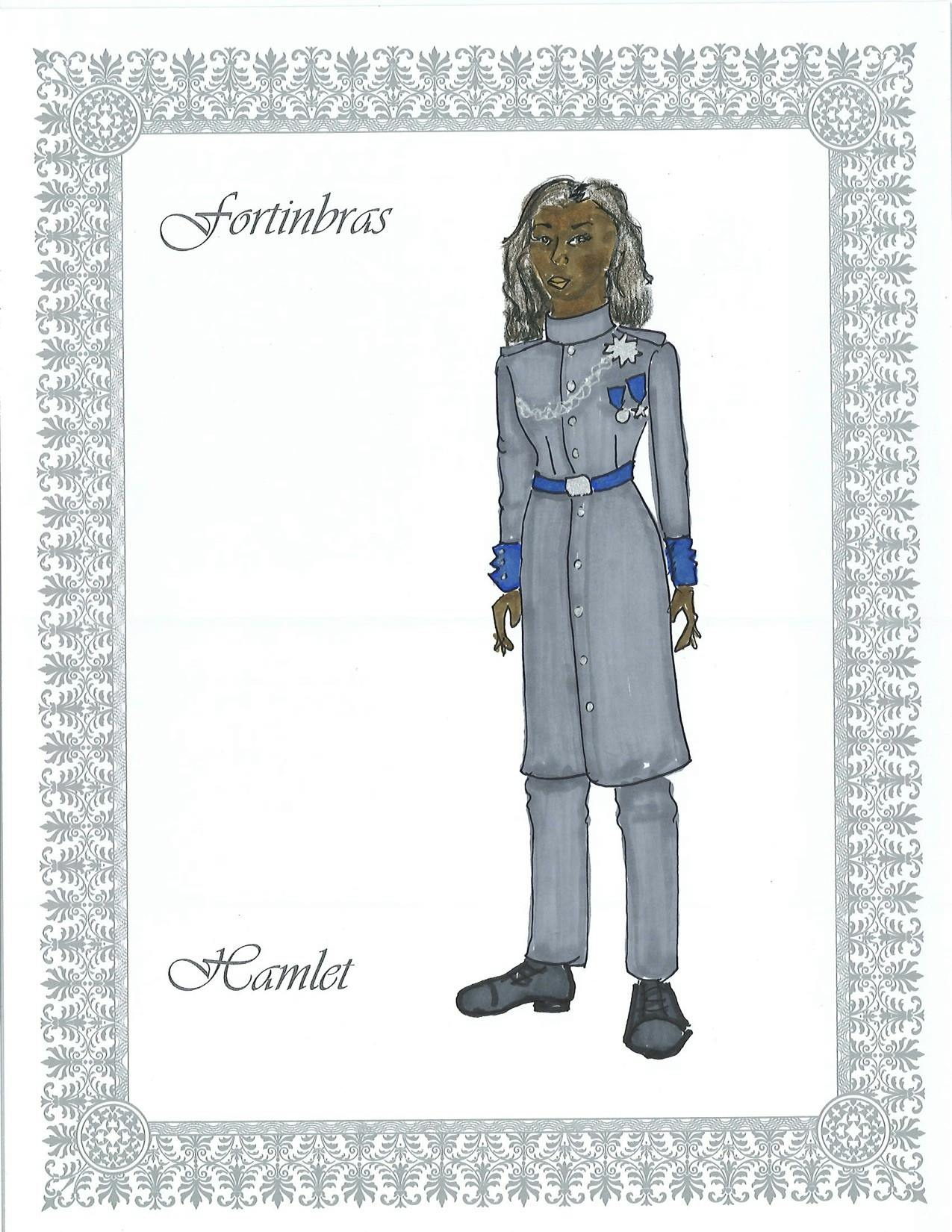

Another gender-swapped character is Norwegian crown prince Fortinbras, who appears after the Danes have all met their end by way of stabbing or poison or poisoned stabbing.

He hangs over most of the play, a threat of a foreign conqueror that becomes a reality by the end of the story when there’s not much left to conquer. It’s not a big role and in some productions, the character is omitted for the sake of a shorter run time.

In IU Theatre’s production, Embry will play the traditionally white male role.

“Fortinbras is a trained soldier, and she is ready to act,” Michaelsen said to the cast while discussing some of the gender changes in the show before the first rehearsal.

As the production’s cast goes around the table to introduce themselves, she is the only black person in the room. The production’s only other black actor, Kenny Arnold, wasn’t at the first rehearsal. Arnold is playing the priest and the ghost of Hamlet’s murdered father, appearing only as a voice over and a lighting effect for the latter. Like Fortinbras, both roles have limited lines in the play.

Most of the lines in the play go to Hamlet himself, played by M.F.A actor Michael Bayler. A baseball cap covers his blond hair during most of the first rehearsal as Bayler’s voice fills the room for hours.

Embry crossed her arms and rested her head on them as Hamlet and Horatio spoke to the ghost of the murdered king, waiting for her turn.

***

Fortinbras is a Scandinavian prince and military leader originally written for a 400-year-old play based on a medieval legend. Embry is a 22-year-old black woman who grew up in an Indianapolis area so surrounded by gun violence it inspired her to write a play she’s hoping to stage next semester as an independent project, which has the working title “Chariot.”

At first, she had no idea how she was going to relate to the role. It takes time to get to a point of connection with your character, and with some it just doesn’t happen.

Embry played an African immigrant named Nomfundo who worked in a nail salon and was being underpaid by the owners.

Embry just felt stupid in the role. She describes roles like that as feeling like someone else’s skin is stretched over her face instead of settling into the character.

Sarah Zygmuntowski

Adrianne Embry speaks on her experiences in IU's theatre department.

She originally auditioned to play Gertrude or Ophelia, but Michaelsen chose her to play Fortinbras instead — a daunting task for her to sink into a role so unlike herself. She watched three different “Hamlet” productions to see how other actors embodied Fortinbras: all three were white men who leaned into the authoritative nature of the role.

Elle Kreamer

Actress Adrianne Embry runs through her final lines as Fortinbras Nov. 13 on stage in Ruth N. Halls Theatre. Embry was shocked when director Jonathan Michaelsen chose her to play Fortinbras in his production of “Hamlet."

Playing Fortinbras didn’t really click for her until one day before rehearsal. She was listening to Houston rapper Megan Thee Stallion, known for songs such as “Big Ole Freak” and for coining this past summer’s social media-dominating catchphrase “Hot Girl Summer.”

Megan is all confidence and precision in her songs, with a mix of attitude and structure that has catapulted her to an up-and-coming class of musicians in a genre famously inhospitable to most women artists.

In “Freak Nasty,” the song Embry was listening to while driving to rehearsal, Megan raps: “And I walk and I talk like a pimp, ‘cause I am.”

Then, it clicked in Embry’s head: If Fortinbras was a female rapper in 2019, she would be Megan Thee Stallion.

Now, she sees Fortinbras being portrayed by a black woman as fitting.

“If that is not the world...how I view black women, we’re strong,” she said. “We carry shit.”

***

Advertisement

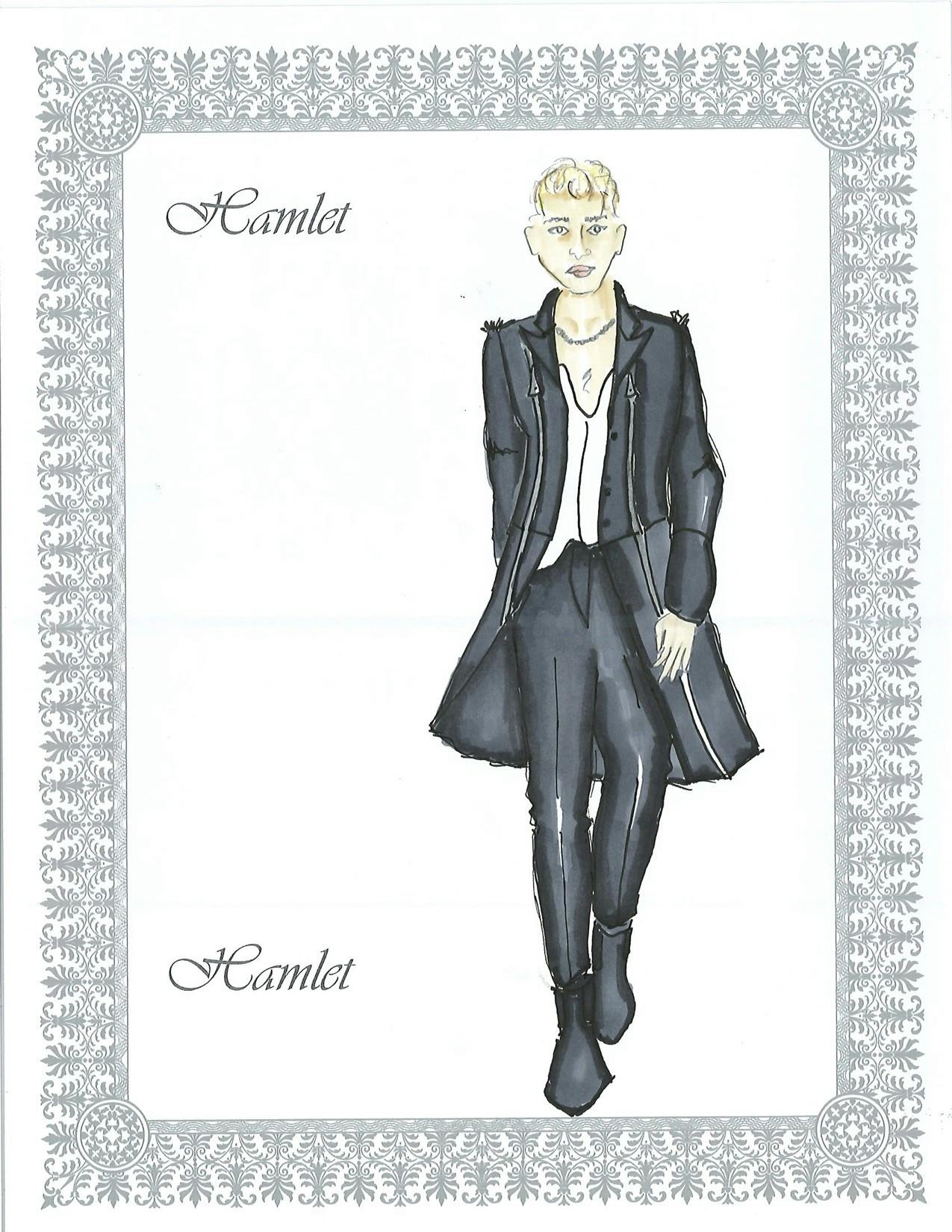

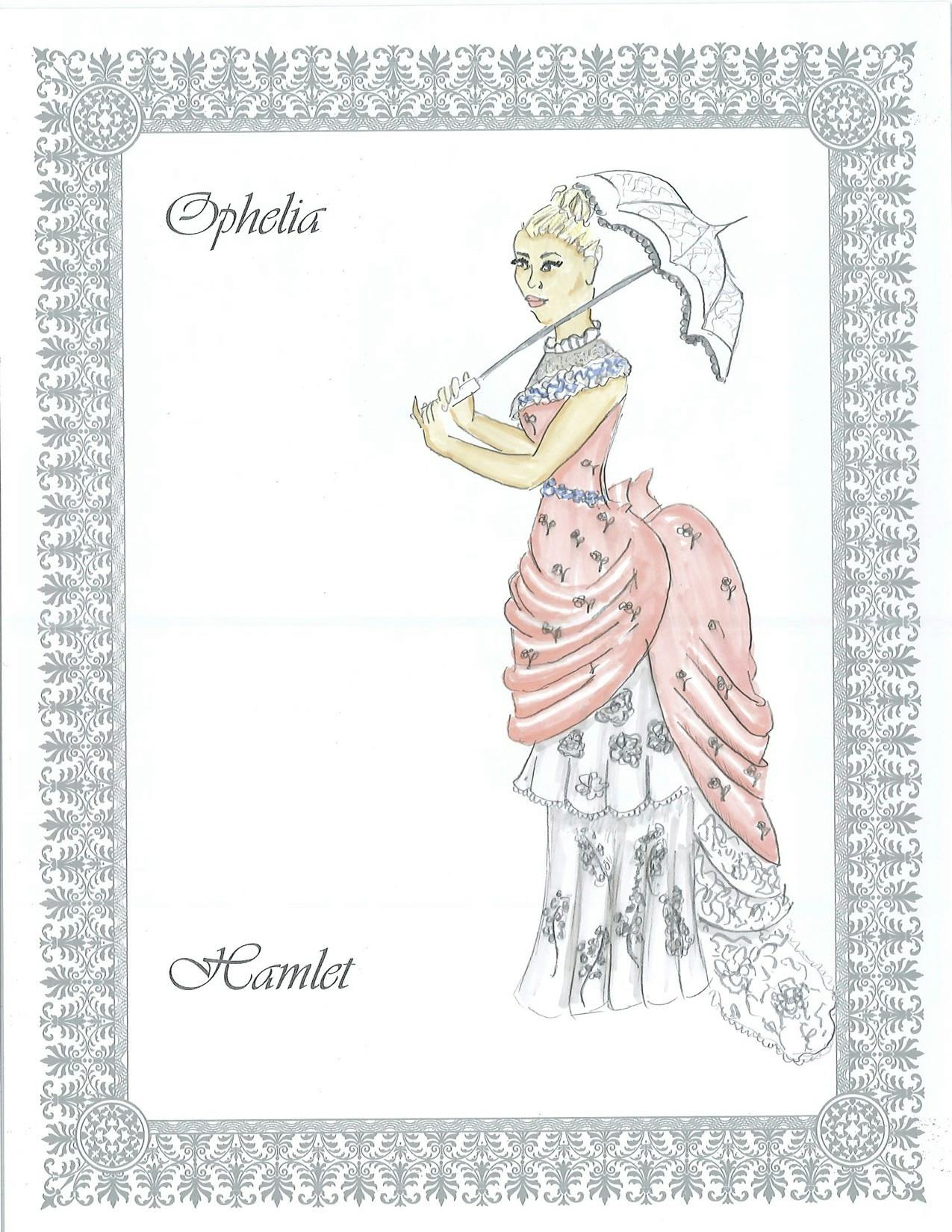

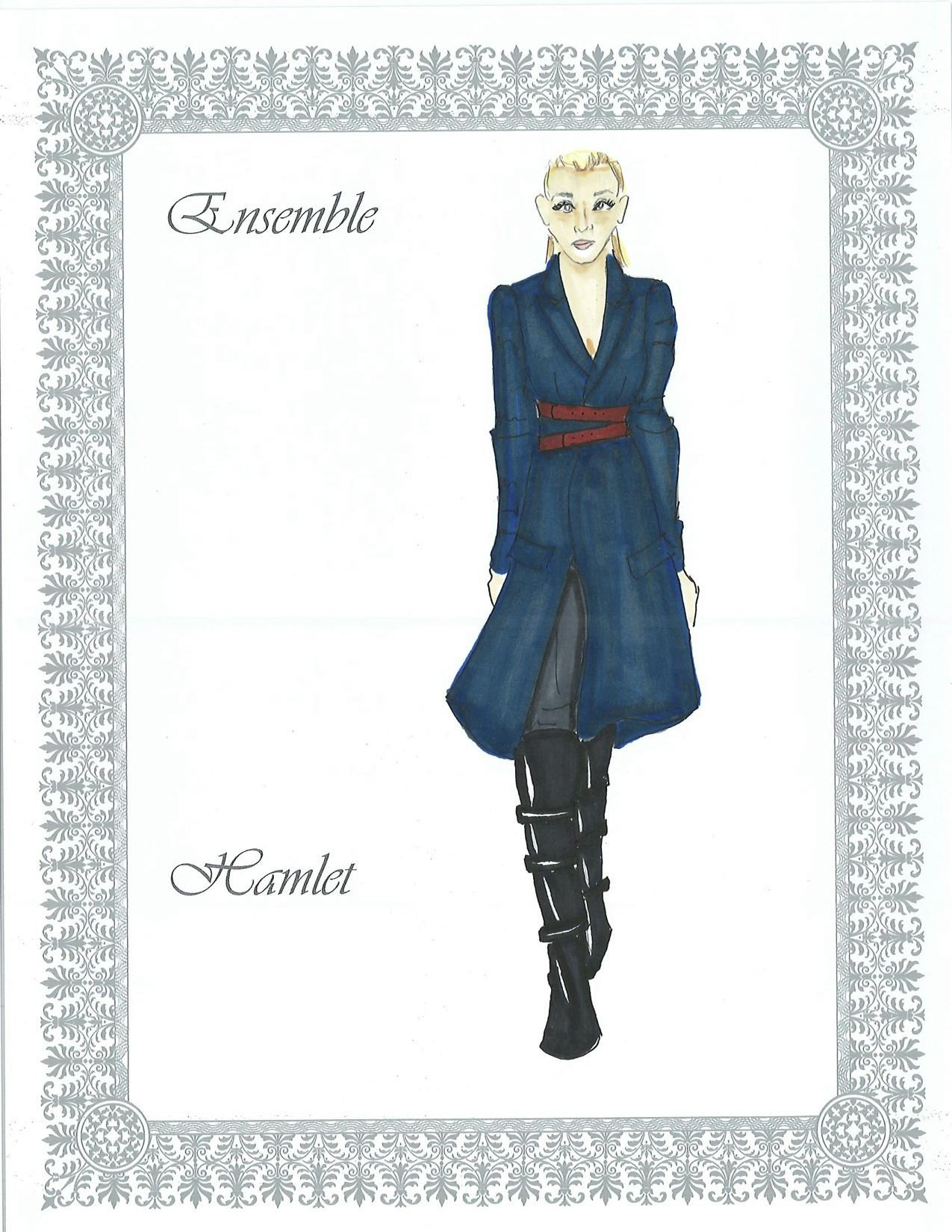

In a side room on the second floor of the theater building, those working in the Costume Shop for “Hamlet” are tasked with a big job: making the production accessible to modern audiences.

Costumes in theater are more than just clothes, they’re intensely purposeful choices. In large theaters, when individual facial expressions can be difficult to see in detail, costumes do a lot of the work of shaping how characters are perceived.

“Hamlet” was originally written sometime between 1599 and 1602, but costume designer Justin Gannaway, who is designing the show’s wardrobe for their M.F.A. in Costume Design, says they always design for 2019.

“I don’t ever judge the success of a design until I’ve heard from millennials about it,” they said. “I design for our generation.”

Gannaway and M.F.A Costume Technology students Ellis Greer and Madi Bell spent hours stitching and sewing fabric to create Gannaway’s vision on the many dress forms, the mannequin-resembling blank canvases for the costumes that fill the room.

In Shakespeare’s time, men portrayed women on stage. Now, in a production with an unusually high number of women on stage, the modern take is mostly manifesting itself through representations of gender. As a non-binary person, exploring gender is a recurring theme in Gannaway’s design work.

Fabrics with feminine touches such as floral flourishes have made their way into masculine roles; Claudius, Hamlet’s uncle who murders his brother and marries the Queen Gertrude in his ascension to the throne, wears a black and red floral print coat throughout the show. Other costumes for men have lace detailing along collars and sleeves.

For Kunkel-Ruiz’s Horatio, one of the genderbent characters, Gannaway’s original design featured a bustle under a coat to create an hourglass silhouette in Hamlet’s confidante. During the fitting, Kunkel-Ruiz was doubtful.

“It’s not feeling right for me, because I feel like Horatio is non-binary,” she said to Gannaway.

Gannaway agreed, and the bustle was gone. Horatio’s final costume features a long coat belted to create a shape that’s feminine without being an hourglass, existing somewhere between the exaggerated shapes of the noblewomens’ dresses and the stark masculinity of the play’s military outfits.

Sarah Zygmuntowski

Justin Gannaway speaks on their interpretation of creating costumes for "Hamlet" in 2019.

In a theater like the Ruth N. Halls, with rows of seats extending into the back of the house, the designs have to say something about the character both when seen by close-up audience members and ones sitting further back.

For Fortinbras’ modified military uniform, the gold chaining coming down from Embry’s shoulder adds another layer of ornamentation to the accomplished soldier. But it also helps build the character: Embry has narrow shoulders, and the gold highlight on the navy fabric helps form a more authoritative, masculine silhouette on stage.

Embry loves the costume. She likes to keep the shoes her characters wear because they make her walk differently for each — she said Fortinbras’ boots, which give her a heavier step, make her feel badass.

But her favorite part of the costume is the gold chaining on the shoulder.

“If that doesn’t say boss bitch,” she said, “I don’t know what does.”

Advertisement

***

Taking a modern approach to a centuries-old play exemplifies a debate that runs along a generational divide through theater, both in IU’s department and nationally: why continue to produce the classics?

While Gannaway has embraced this production’s genderbending, they say the cause of it – the original lack of roles for women – along with the mistreatment of Ophelia and Gertrude by the source text can’t be forgotten.

Elle Kreamer

Actress Isabelle Gardo, left, bows her head during a tense scene with actress Anna Doyle on Dec. 3 in Ruth N. Halls Theatre. During the 1600s, it was common for men to play all the roles in performances, even those even those that were originally cast for females.

“As theatricians and designers and tastemakers, we have to have those conversations,” they said. “At some point, we have to consider: do we phase these classics out?”

Embry was Shakespeare-averse for a long time; she didn’t see herself in those shoes, because actresses who look like her didn’t often get to be in them.

“The goal of this project is to embolden a positive shift of culture in which every student feels supported,” wrote department academic adviser Kim Hinton in a 2018 email planning the Not in Our Haus protest. Hinton died earlier this year from a pulmonary embolism at age 47.

Now, over a year after the Not in Our Haus protest, students are still trying to achieve that goal while acknowledging the original protest was ineffective.

“We got the same results as if we didn’t even do it,” Embry said.

Now, students of color within the department are trying a new technique: making their own opportunities. Embry is the co-president and co-founder of Black Brown & Beige Theatre Troupe, after encouragement from theater professor Ansley Valentine.

The troupe, which was formally started this fall, is planning different ways to elevate student performers of color starting next semester: a showcase, a partnership with the Black Student Union, collaborating with prominent student theater troupe University Players, an independent production of Embry’s play, “Chariot,” and a production of the play “The Colored Museum” by George C. Wolfe.

Some of these are dependent upon departmental approval —some applicants get higher priority and better chances at departmental approval, such as M.F.A projects or University Players productions. Embry said that if the department wants to be inclusive, the Black Brown & Beige Theatre Troupe should have a spot on that list.

“This is a university that, and especially this theater building, loves to claim that we’re so diverse and inclusive,” she said. “It’s like, okay. Make sure my troupe gets to put on these stories.

***

Fortinbras is the character who says the last lines, a lament for Hamlet’s death and for the state of affairs in Denmark, as she arrives to take over.

Each time Embry walks on stage as Fortinbras to see the slain Danes, she said she can’t help but think:

“You white folks messy.

Let me help you out."

While Fortinbras is a minor character in the production, she exists largely as a foil for Hamlet: Hamlet’s fatal flaw is an inability to take action, and Fortinbras is all action.

“For me, with sorrow I embrace my fortune,” she says as she orders those left to now serve her.

In the last moment in the production, before the cut to black and the cast takes a bow, Embry takes centerstage and looks out toward the audience as Fortinbras becomes Queen. The rest of the stage is dark.

Now, the light is on her.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misstated part of the content of the play "Nice Nails." The IDS regrets this error.

Add your voice to the conversation. Write to us at letters@idsnews.com.