He sees them go up and down. Up again, back down again.

TJ Covey watches the playground swings arc through November air. One passenger, his 4-year-old son Jaxan, belts a rendition of “I Believe I Can Fly.” The other, his 8-year-old son Deven, nears his apex and lets go.

He nearly lands it, but his feet slide, and he falls hard.

Then he bounces up, and Covey laughs, thrilled just to watch his sons play. One day a couple of years ago, he tried a similar outing and wound up lying in his truck while the boys stayed outside. He’d taken a dose of Suboxone, a drug used to treat opioid addiction, too soon after shooting heroin, and by the time he got to the park he’d gone into painful withdrawal. He felt like he was going to die.

Not long after, Covey spent more time away from his sons. He waited in jail from June 2015 to last September on drug dealing charges, eventually dismissed.

He knows how fragile sobriety can be — he’s tried it before, been up and down and back up again. Now he’s resolved to beat an addiction that’s ravaging much of the rural United States.

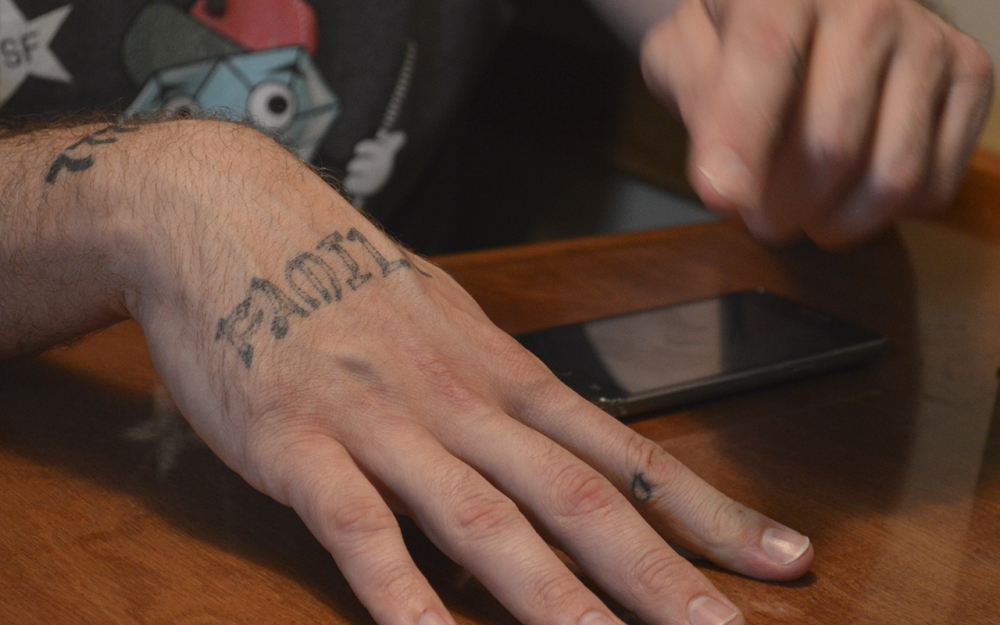

At this park in Bloomington, he is 60 days sober. It is only his second period of sobriety since he was a teenager not counting times he’d been in jail. The boys think their dad was sick. They don’t know their dad, now 33, has known pain pills and heroin for more than half his life, that he struggled without access to affordable rehab, medically assisted treatment or needle exchanges.

People like their dad are at the core of a deadly epidemic . According to the Centers for Disease Control, heroin-related deaths outnumbered gun homicides nationwide for the first time in 2015.

Covey’s kids are rambunctious and endlessly curious. He had the same spirit as a youngster, he says. As kids in rural southern Indiana, he and his cousins entertained themselves by jumping from the high loft in his grandfather’s old barn into the mattress-padded bed of an old dump truck. He’s always been curious and starved for adrenaline — for higher climbs — and he thinks that combination has something to do with his lifetime of struggle with addiction.

He knows about hard landings — overdose rates, jail time, the needle-spread wave of HIV and hepatitis C sweeping southern Indiana. Lately he’s been waiting on his own blood test results. He feels sure he’s HIV-free, but knows he shared needles with people who had hepatitis.

He also knows some people try to help soften the blows. After jail, he landed in the Amethyst House, which provides housing to recovering IV drug users, and he’s happy to see the relatively new local needle exchange, but he wishes he’d had more options when he was using.

Opioids have settled in the heartland, but how should the epidemic be handled? Is this a criminal crisis or a public health one? It’s a conversation not just about the climb and the fall but about the landing – whether people plummeting now deserve a cushion to land on or just the harsh crack of their bodies on impact.

At the heart of the opioid epidemic lies a handful of middle-American states with high populations of white, rural, working-class people. Among them is Indiana, which, having seen a confluence of high-profile disease spread and legislative controversy, also is at the core of one of the crisis’s most significant conversations.

This dispute does not divide evenly among party lines. Its participants are legislators, medical experts and advocates, and its shockwaves reshape the terrain for the people on the crisis’ front lines.

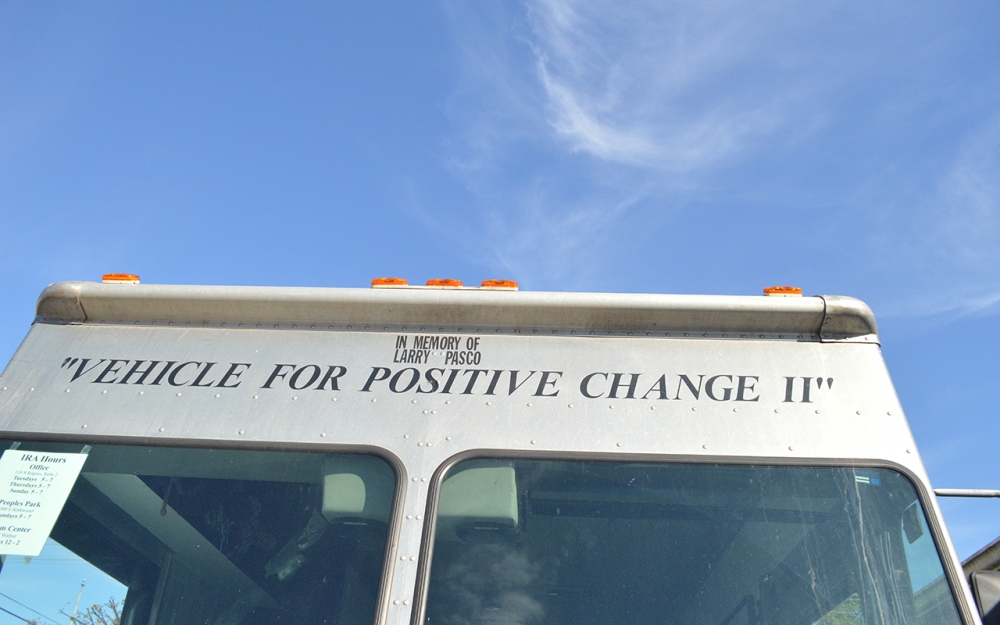

On an October Sunday one of the battle’s pieces of artillery coughs to life. It’s a sizable thing, a Grumman van with silver aluminum siding. It is militaristic with its doorless cab and blunt nose. One side displays the logo of its owner, the Bloomington-based Indiana Recovery Alliance. The van’s name is emblazoned above the rear door: “Vehicle for Positive Change II.”

Chris Abert, the man with the keys, started delivering clothes and blankets to homeless people by bike with some friends in 2014. Since then, the project has expanded to an office on Rogers Street and this van.

Contained within the van’s armored walls are tools for survival. There are unpressed bottle caps, condoms, pamphlets, biohazard containers and, most prominently, clean hypodermic needles. These are defenses against the wave of hepatitis Cand HIV spurred by unclean needle sharing. In the first year after it opened in September 2015, the Monroe County needle exchange served more than 600 people, Abert said.

Less than two years ago syringe exchange programs were illegal under state law. Then, in early 2015, southern Indiana’s Scott County saw an HIV outbreak of shocking proportions — around 200 cases — tied to needle sharing among opioid users. In May 2015 lawmakers allowed for the creation of needle exchanges.

Abert works near a series of blown-up pictures of needle tips in the IRA’s office. The first shows a needle that’s never been used with clean lines leading to a sharp point. By the third and final picture, of a needle used six times, the point is curled and crumbling. The façade is worn, like molten rock.

He and some volunteers finish their preparation for the day, and just after 5 p.m., he parks the van at the north side of Peoples Park. People start rummaging through the bins, and a guy in a baseball cap shouts, “Yeah, bring out the keg!” as volunteer Sarah Cahillane sets up coffee.

Most of the people at the park just take coffee or clothes, but within the first half-hour, a dozen or so people emerge from the van with plastic grocery bags bursting with items.

Abert moves around the van and the park and talks to participants and other people he knows.

He chats for a while with one woman, a longtime Bloomington resident who now lives in Ohio. She tells him she’s been clean for three months. Before that she used the needle exchange, and she credits it with giving her the tools she needed to save the lives of friends who overdosed. Before she can explain, Abert points out a police officer standing near the van, and the woman, explaining she has a warrant out, shuffles away.

Abert is irritated. He fears the cop’s presence will spook already wary participants, and he’s unsure of his intentions. Police can’t legally arrest people for using needle exchanges. Abert turns his back to the officer, takes out his phone and snaps a selfie with the officer in the background.

The crowd dwindles by 7 p.m., when the volunteers start packing up the van. Abert asks Cahillane how many people they saw today. Sixteen, she says, most in the first few minutes.

“Obviously slowed down in the last 40 minutes,” another volunteer says.

“Since the fucking police showed up,” Abert responds.

He and Cahillane load into the cab of the van, and the engine coughs to life again. Then it pulls forward, rolls over a speed bump and rumbles away from its battlefield.

Programs like needle exchanges, safe injection sites and the distribution of the overdose-reversing drug naloxone fall under the banner of harm reduction.

Their toughest enemies are massive but microscopic: diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C, that can be transmitted by dirty needles.

HIV is more debilitating and, with situations like the Scott County outbreak, has gotten more attention as the opioid crisis worsens. However, experts from IU Health’s HIV-focused Positive Link program point out hepatitis C can have serious implications for a whole region’s health.

“You can look at hepatitis C as a precursor because it’s transmitted more easily than HIV, but it’s transmitted the same way,” program director Jill Stowers said.

Hepatitis C can move quickly, prevention coordinator Emily Brinegar added, because it can survive for some time outside the human body. That means that even intravenous drug users who don’t share needles can still transmit it by sharing other drug equipment.

The prevalence of IV drug use in Scott County and lack of resources for users made the HIV outbreak less surprising for experts, Stowers said. In Monroe County, hepatitis C is a visible factor. When State Health Commissioner Jerome Adams declared the county’s health emergency in December 2015, he did so for a rise in hepatitis C cases.

Between September 2015 and September 2016, the county saw an estimated 200 new cases of hepatitis C, Abert said. In October, during a harm reduction panel at the Monroe County Public Library, he said factors like that could put Monroe County at risk for a Scott County-scale HIV outbreak.

Needle exchanges date back to at least 1983, and they now exist in 40 states. CDC studies have put the cost of preventing one case of HIV via needle exchange between $4,000 and $12,000 compared to $400,000 for a lifetime of HIV treatment. A 2016 study of the Scott County HIV outbreak published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggested access to clean needles could have prevented the outbreak.

Since the mid-1980s, opponents have argued the programs promote drug use and other criminal activity.

Several federally funded studies have found no link between needle exchanges and increased drug use, but the mindset may have resulted in Indiana’s longstanding ban.

In March 2015 former governor Mike Pence issued an executive order allowing clean needles to be distributed to quell the Scott County HIV outbreak. Prior to that, he staunchly believed needle exchanges encouraged drug use, according to an August profile of the now-vice president in the New York Times. When he did agree to allow programs, he wasn’t swayed by evidence, rather by prayer.

Indiana’s law allows the programs only as reactive measures, not preventative ones, and the programs can’t receive state funding.

The exchanges have to meet a series of bureaucratic requirements. A local health officer must declare an HIV or hepatitis C epidemic connected to drug use, and the state health commissioner must declare a public health emergency. They can only operate as long as the emergency remains in effect.

A needle is one of the things that can land IV drug users in jail on felony charges. In 2016 alone, according to Indiana Department of Correction data, 59 people were committed to the DOC on felony charges with syringe possession as their most serious offense.

Incoming Governor Eric Holcomb told the Associated Press in early January he wants to eliminate some of those restrictions and allow local officials to establish needle exchanges.

It’s hard to quantify the Monroe County program’s effectiveness in stemming the spread of disease in the short time it’s been open, Abert said. But if results do come down the road and laws don’t change, the future of the needle exchange could be in question.

“If we lower the hepatitis C rates in Monroe County, we won’t be able to do the needle exchange anymore,” he said. “It’s so fucked.”

It’s 2009, there is a Subway cash register, and Covey is taking $30 from it. This is not a holdup — he works here. This is not for drugs — he is two years sober, but his record makes it hard to get a job that pays enough to live, and he has an electric bill to pay, and now he is caught, and back in jail, and the drugs are here, too.

Somewhere there is a doctor prescribing opioids for a 16-year-old Covey’s growing pains. Then he realizes how good they make him feel, and how good other drugs make him feel, and now, at 18, he’s blacked out on Xanax and stealing $20 in quarters from a laundromat.

Here is a locked door, on the other side of which has been a fight with his wife, and now the door is broken down.

Here is a toilet in a public bathroom, and here is him pulling water from it to shoot up.

Somewhere, there is this, the memory of a sentence spoken by another addict: “I’m caught in the middle of a war I didn’t sign up for.”

Crystal Scrogham still shoots anything she can put in a needle.

She visits the needle exchange a couple of times a week with hopes not to get sicker. She knows people who won’t. They’re too afraid of being targeted by police. She goes by Crystal Weber, though a search in MyCase, Indiana’s public case summary service, shows that’s one of many aliases.

On another fall day in Peoples Park, a day without the van, Scrogham, 34, recounts the timeline of her addiction. There is no definitive or singular experience with opioid addiction, but that basic arc recurs: the highs, the rapid descents, the landings.

She found the heroin while digging through the tent in her backyard. She was 10, and her parents — both heavy drug users, she said — had let a transient hunter pitch camp behind their house.

She had been smoking and drinking since she was 4 or 5 years old. At 9, she started smoking in front of her parents so she wouldn’t have to sneak cigarettes from her mom. By the time she found the drugs in the tent, she was curious what heroin would be like.

That first time, she failed to finish the injection. Within the next two years, though, she was shooting heroin regularly. By her mid-teens, she was a “full-time addict.”

Around that same time she thinks she contracted hepatitis C. She’d use whatever means she had to shoot drugs. She would take dirty needles her diabetic grandmother had used and use water from filthy puddles to cook the heroin. She was diagnosed with the disease at 17.

She’s overdosed and been brought back to life with naloxone. She sometimes has seizures spurred by the lights from passing cars.

For years she’s had recurring dreams. One told her she’d die at 33, and so on the eve of her 34th birthday, she locked herself in her mother’s apartment. She wouldn’t leave until after midnight, when she’d safely reached the other side.

22-year-old Tristan Kingsolver is younger than Scrogham and came later to drugs — his story sits on the crest of the epidemic’s wave — but he too saw how fast they take command.

On Aug. 28, 2015, his 3-year relationship with his girlfriend fell apart, and he started drinking a case of beer and a bottle of Jack Daniels every night. In early October, he began snorting heroin to numb himself. On Dec. 13, sixteen days after he started shooting meth, he lost a good job at Cook Pharmica.

Last year he went to jail on breaking-and-entering charges – he said he’d been robbed and wanted his stuff back.

Though opioid users may find themselves in jail on possession or paraphernalia charges and though jails do provide some pathways to recovery, Kingsolver said in his experience, jail isn’t necessarily a conducive environment for staying clean. He saw heroin, meth and marijuana in the Monroe County jail, he said — “more drugs per capita than the streets.”

When he left, after four months, he moved into the Amethyst House and set about righting his life. He’s never fully aligned with any one religion, but he’s in touch with his spirituality, meditates regularly and reads books on religion and philosophy, he said.

Kingsolver skydives, too. In October he went on his second jump. Letting himself go thousands of feet above the Earth makes him feel closer to God.

In January, he violated his drug court and went back to jail.

On a December afternoon, TJ Covey watches Jaxan plays video games on the floor of his mother’s apartment. Jaxan is home from school with a cold, and Covey has left the Amethyst House because curfews kept him from spending enough time with his kids. Now he lives at his ex-wife's apartment, where he can be closer to the boys.

“I don’t like being sick,” Jaxan says, eyes glued to the television.

“Yeah, me neither,” Covey says. He’s getting over a sinus infection, but he’s also recently gotten a diagnosis that’ll take longer to kick. Before he left the Amethyst House, a Positive Link representative returned with his test results. Hepatitis C is in his blood.

He’s spent the past couple of weeks learning all he can about the disease. It’s seen medical advances in recent years, but it’s more than a mild inconvenience or a case of sniffles. It’s a direct, physical link to a life he hopes he’s left behind.

The test results didn’t surprise him. Somewhere in the back of his mind he knew, he said.

He’s applied for insurance via the Healthy Indiana Plan, but he’ll have to see a doctor for more tests before moving on to treatment, if he’ll be able to move on to treatment. It depends on a handful of factors — how much of the virus is in his body, what strain of the virus he has, how much it’s damaged his liver.

He hopes for one of the more modern treatments, which can treat the disease in as few as a dozen weeks with side effects less debilitating than those of old standards.

For now his own blood makes him nervous. Hepatitis C can typically only be transmitted by blood-to-blood contact, so it’s mostly contracted by IV drug users, but worst-case scenarios play out in his mind. What if he cuts himself shaving, and someone accidentally uses his razor?

He hasn’t told many people about the diagnosis yet – family, mostly. The other day he heard someone make a jab about someone being a “hep-havin’ junkie.” It was almost enough for him to yell at them, “I’ve got hepatitis.”

He wants a new job, though his criminal record makes it hard to find one. He’d like to advocate for people who are homeless and people with mental illnesses. Maybe he will be a drug counselor or lobby for legislative drug reform. After all, he’s lived it.

As much as anything, he wants to be with his boys. Their dad has been sick, and he will be sick again, but someday, he’ll explain it all to his sons — how he found himself caught in the middle of a war he didn’t sign up for.