A man and woman pushed carts filled with items down the sidewalk on West Seventh Street earlier this month. When they got to where the Stancombe House used to be, they stopped.

The brick fireplace from the front parlor room was still there. The front step was still there. Everything else was rubble, broken glass and shredded floral wallpaper. Faded yellow stucco still clung to a piece of what used to be the kitchen wall. Sitting on the front step was a stone frog, a little worn, with only hints of green paint left.

Ty Vinson | IDS

Steve Stancombe and Rosemary Stancombe Crockett stand Oct. 14 where the front step used to be of 523 W. 7th St., their grandmother’s home. The house had been in the family since the 1940s and was demolished in September.

“What used to be here, a house?” the woman asked. “Looks like it burned down.”

The woman picked up the stone frog and examined it for a few seconds. Then, she placed it into the crook of her arm, put a hand on her cart and continued down the sidewalk.

To answer her question, to understand what used to stand there and what it meant, you have to go back in time, back through four generations.

A lot of things began and ended at 523 W. 7th St. – childhoods, a million meatloaves, even lives. The house caused a public controversy when wreckers took it down a few weeks ago. The city wanted to protect it. The family who owned it wanted it gone. Now the family owes $83,000 in fines.

They knew they’d missed some steps, and they knew the city would object, but they felt they had no choice. The house that held 90 years of their memories took a lot of trouble with it when it fell.

Courtesy photo

Steve Stancombe drew the layout of the Stancombe house from memory.

Steve Stancombe stood beside the flat space where his grandparents’ house used to be. It was cold, one of the first cold days in October.

He put his hands in his pockets.

“A lot of memories here,” he said.

The dining room was gone. There wouldn’t be any more family dinners.

The porch chair was gone — the one he used to lean back on as a kid, copying his grandpa. The porch is gone. Steve, 66, was able to recover some slats from the porch. They still had the blue shade of paint on them.

“It don’t look so big when there ain’t nothing there, ya know it?” Steve said. Steve’s sister, Rosemary Stancombe Crockett, got out of her car and stood next to Steve. She shivered.

“Just doesn’t look as big anymore, does it?” she said.

Steve and Rosemary walked up the sidewalk. Steve stepped into the freshly laid straw and tried to map out where the front step used to be.

Steve tries to keep connections to the past. He bought a ’52 Pontiac so he could have something from the year he was born. He hasn’t restored it much, though people always tell him he should.

He always responds with, “It’s only original once.”

Rosemary, 64, grabbed a set of aluminum cups from the rubble. Steve plans to pass them down to his son before he dies.

“There was a lot of livin’ goin’ on in that house,” he said.

Advertisement

First, the demolition crew went through the house to salvage everything they could. They took out the stoves, cabinets, countertops, windows, mantels. They began to dissect the house piece by piece. The wrecker tore into the roof. It was all sorted, crushed and disseminated to landfills.

Diana’s husband, Dave Holdman, watched the house come down. She came by after the roof was gone, but didn’t stay. When the house was gone, she called her mother, Judie. Judie couldn’t bear to see the house, not after what happened there.

"It's finally done and over with,” Diana said to her mom.

They cried over the phone.

An engineer hired by the family inspected the house to determine whether it could be saved. When he walked through the house, he laughed.

The support underneath the house had rotted in the dirt. The pipes were broken from constantly freezing over. Fixing the problem would require lifting the house and setting it back down on new support, all while praying it didn’t fall apart. It also would require a lot of money.

Diana and Dave went to the house and saw there had been another fire lit on the inside, destroying more of the house. They had to make a decision. Dave called Judie. Take it down, she said, once and for all. Judie was ready for it to be gone, and the bad memories along with it.

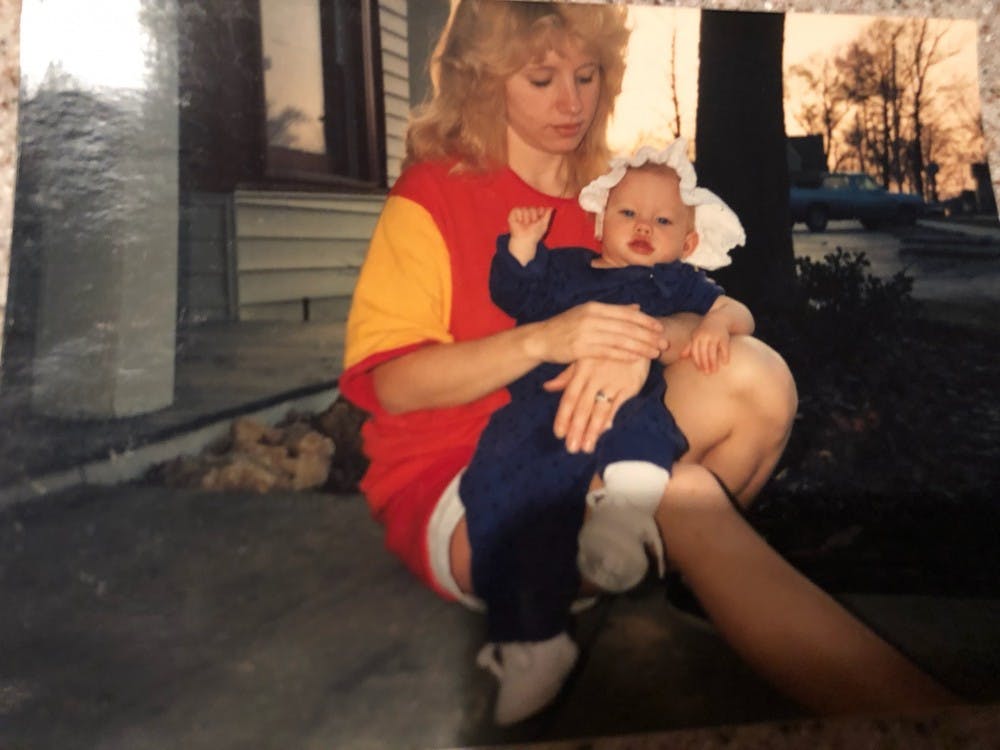

Courtesy photo

Diana Rush Holdman holds her daughter Amanda on the front step of the Stancombe house. Diana lived in the house on and off with her mother, Judie.

In May, Dave put in a request for a demolition permit.

The family met with the Bloomington Historic Preservation Commission and the request was tabled. The meeting was moved. At the next meeting, it wasn’t discussed.

The next meeting was supposed to allow the family to voice why they wanted the house to be demolished. They even brought a sketch of what they wanted to build in its place: a Queen Anne single-family home.

The commission surveyed all the adjoining houses and then, on Aug. 7, voted to designate the neighborhood as a protected district and sent the decision on to the city council.

Diana and Dave didn’t know about the meeting, they say. They didn’t know the home was protected by city ordinance at that point.

Diana figured there would be consequences, but the house just wasn’t built well. “If we could’ve saved it, we would’ve done it,” Diana said. “You have to start from good bones.”

Diana Rush Holdman and other members of the family went through the house and salvaged what they could. Old photos of Easter egg hunts and naps with grandma, Carrie Stancombe. Photos of Diana and her siblings. Letters written back and forth between Carrie’s seven kids while they were in the war. Stained glass, doors, cups, old clothing, detached doors, a white corner cabinet, a set of eight ship mugs. The Stancombe family crest.

The house sat empty for 13 years.

Homeless people would often break in and sleep there. Fires were lit in the fireplace, even though it had been plugged long ago. Toilets didn’t work, so people would use bottles or 5-gallon buckets.

The fires slowly destroyed the house, charring the inside of the fireplace and burning the carpet around it.

Diana and her husband Dave started thinking about what to do with the house. It had become an eyesore to the rest of the neighborhood, which is full of historic houses in the section of town called the Near West Side. The house was right across the street from Fairview Elementary, and people were constantly in and out of it, no matter how often they boarded it up.

With colder weather would come more fires in the plugged fireplace. Someone could get hurt.

When they went inside, Diana and Dave found broken glass, 5-gallon buckets of sewage, probation papers, dirty needles and around 40 bottles of urine.

There were always offers from the church next door, but the family felt the house would just be torn down to make room for more parking spaces. Every year, people would ask Judie what she wanted to do, and she always avoided the question. It hurt to think about it.

Advertisement

Judie had gone to stay with her daughter Diana for a few days when they both realized they hadn’t heard from Judie's son Kenny Rush. He just got divorced and was living with his mom while he worked as a mason. He would usually call to check in, but when he didn’t answer the phone for a couple of days, Judie and Diana worried.

When Judie and Diana arrived, they found blood all throughout the house, on the back patio, seeping down rocks. They found Kenny’s body on the floor of the back room near the bathroom.

The details of the crime are sketchy. It was never solved. All they know is Kenny was killed by “blunt force trauma to the back of the head.” It could have been an altercation at the home, it could have happened somewhere else and Kenny tried to make it back home. Maybe they’ll never know for sure. He was 45.

After Kenny died, Judie couldn’t bear to be in the house anymore. She shut the house up and said she would never go back.

The roots from the willow tree out back started growing into the pipes, so the family had to cut it down. In its place, the Stancombes started a tradition that lasted about seven years. Instead of a plastic Christmas tree or one with its end sliced off, the family would buy one with a healthy root ball. After it lived its life indoors for the holidays, Judie, Diana and Dave would take it outside and plant it on the edge of the property bordering North Jackson Street.

The trees grew to more than 20 feet tall.

Kenny had been working on a wall-building project for the Scholars Inn Bakehouse on College Avenue when he came across a stone frog painted green. He loved to find random, weird things like that to give to people he knew. So, he set it on the front step of his mother’s house on West Seventh Street.

Carrie Stancombe told her granddaughter Judie to not worry so much about the house. She joked she thought someone built the house drunk, cutting so many corners you could stand in the front door and roll a marble all the way out the back.

Carrie died in February at age 86. The house sat empty for six months.

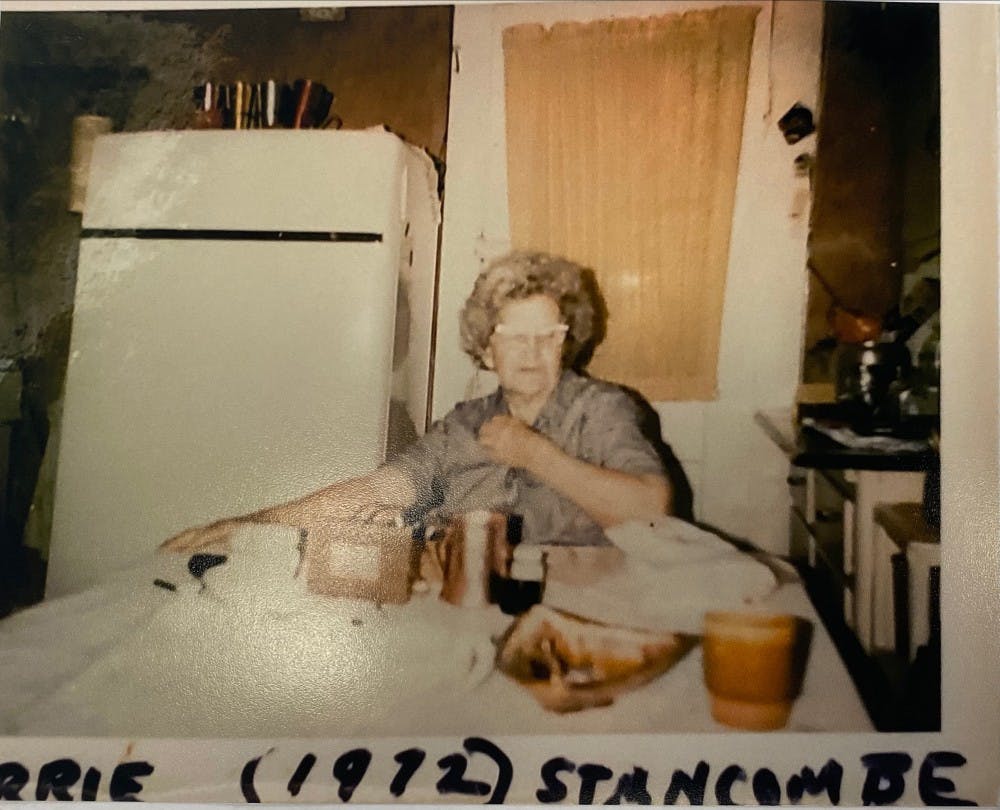

Courtesy photo

Carrie Stancombe sits at the dining room table of her house in 1972 at 523 W. 7th St. Aluminum cups can be seen on top of the fridge, and they would rattle when people walked in.

For Christmas, Carrie and her grandkids decorated the fireplace mantel with pine boughs and stockings. The family didn’t have much money. Diana would sometimes find marbles in her stocking. Carrie would always put up a little silver Christmas tree with blue balls behind the couch on a stand. Though it was small, Diana was smaller. She always thought the tree was big.

Kenny was 7 when he ran down the brick sidewalk on West Seventh Street with an arrow in his hand. It was a game of Cowboys and Indians, and though the arrow was a toy, the tip was real and sharp.

His mother Judie told him to stop running with it in his hand, he could get hurt. He stopped, but when he did, he fell on the arrow and it went straight through the roof of his mouth. Judie had to cut the arrow down so he could shut his mouth, then she took him to the hospital.

Diana took her first steps in the hallroom just before the kitchen. It was the only halfway level part of the house, and there was very little in it, so it was safe to fall in.

That same year, her father fell asleep at the wheel on his way to a duck hunting trip, drove into an embankment and died.

Carrie watched a lot of wrestling. Everyone who walked into the house knew when she was watching AWA All-Star Wrestling. The volume would be cranked up on her little silver TV that sat on a silver tray. She liked Dick the Bruiser, the “World’s Most Dangerous Wrestler.” He won a lot of matches. She’d yell at the TV anytime he did anything wrong or lost a match.

Granddaughter Judie told her she needed to calm down so her blood pressure wouldn’t spike. Carrie was in her 70s after all, it probably wasn’t healthy to be screaming at the TV all the time.

Judie broke the news to her grandmother that wrestling is staged — not real. It broke Carrie’s heart. It was like a child learning Santa isn’t real.

Advertisement

Steve would copy his grandpa Mose and sit in a chair on the front porch of the house and rock it back until it touched one of the posts, acting like it was a rocking chair. He would sit and watch people walk by, but he was always told not to talk to strangers. He could recall steam engine trains going through Bloomington and the black smoke crawling down the brick streets.

On the Fourth of July, the family would drag a couple picnic tables out to sit under the willow tree out back. But the kids weren’t allowed to swing on the tree. That got them in trouble.

Instead, they would go across the street to Fairview Elementary School. The kids would climb the fence and play on the playground, the swings, the monkey bars, the slide. It made Steve and his sister Rosemary wish they were old enough to go to school already. Some days the children would place a pillow on the large white sill of the bay windows in the parlor room, open the drapes and watch the kids play.

Diana, Steve and Rosemary would finish playing on the playground and go back to the house to get a sandwich from the woman Diana called “Granny Good Witch,” or as we know her, Carrie Stancombe. Diana called her that because no matter what someone would say about somebody else, Granny Good Witch would respond, “You never know somebody else’s troubles.”

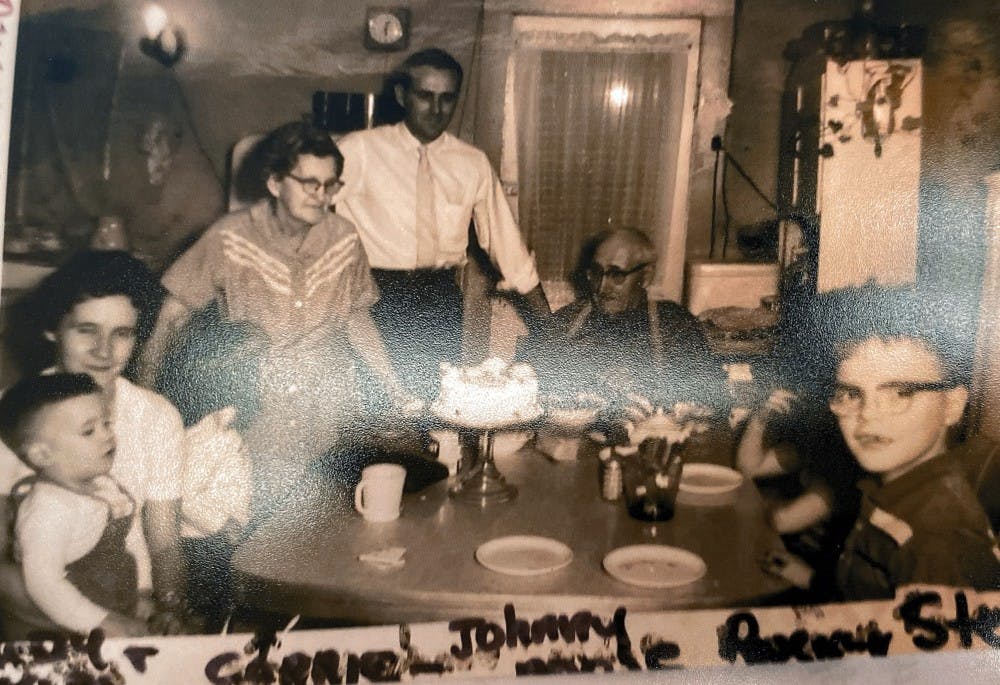

Courtesy photo

The Stancombe family sits around the dining table in the 1950s. Steve Stancombe, far right, can be seen wearing glasses and looking at the camera.

Grandmother Carrie always seemed to be at her little Warm Morning stove cooking something. She would wear an apron, usually one embroidered by her daughters. One had an embroidered terrier on it, similar to the one Carrie had for almost 20 years. Another was decorated with flowers and vegetables, like a garden.

Carrie was known for meatloaf, pot roast, homemade chicken noodle soup and apple pie. She never had recipes written down, they were all in her head. It was a pinch of this, a pinch of that, every time. The only recipe she wrote down was for persimmon pudding, after family members begged her for it.

While she cooked, she would talk to herself like nobody else was around.

Every time Rosemary would walk into the house, she could hear a set of aluminum cups rattling on top of the fridge. It sounded just like bells.

Carrie and Mose Stancombe moved to Bloomington from Vevay, Indiana. They started renting a house built in the 1890s at 523 W. 7th St. Mose began working in the Showers Brothers Building a few blocks down while Carrie stayed home. The house was one of two central parlor homes in Bloomington. After some years, the man they rented from offered to sell the house to Carrie and Mose. He took the rent they had paid so far as the down payment.

The walls were covered in floral wallpaper. The kitchen was a yellow stucco and decorated with commemorative dishes. There was no central heat, just two warming stoves, and the fireplaces let in more air than they heated.

Carrie and Mose had seven kids and one bedroom. Their granddaughter Judie was 5 when they moved in. Carrie and Mose turned the left parlor into a living room and the right parlor into a bedroom. They set a bunch of aluminum cups atop the refrigerator.

The little house became known, then and forever, as the Stancombe house.

Add your voice to the conversation. Write to us at letters@idsnews.com.

Ty Vinson | IDS

TOP PHOTO Steve Stancombe and Rosemary Stancombe Crockett stand Oct. 14 where the front step used to be of 523 W. 7th St., their grandmother’s home. The house had been in the family since the 1940s and was demolished in September.

CORRECTION This story has been updated to reflect the passage of time since the demolition date. The IDS regrets this error.

Like what you're reading?

Support independent, award-winning student journalism. Donate.

© Copyright 2019 Indiana Daily Student

Back to idsnews.com