A nervous hand rose to knock on a grey door deep within Assembly Hall. Then it paused.

Few reporters would dream of walking into one of college basketball’s famed arenas, strolling right down to the head coach’s office and entering. Even fewer would do it to Bob Knight in the winter of 1985, during one of the General’s worst seasons at IU.

Only John Feinstein would do it three hours before tipoff.

Feinstein was lucky though: He was on the List that lived in Knight’s mind. For those writing about college basketball in the 1980s, it was an exclusive one. If you were on it, Knight would give you anything. Interview requests were welcome, access unprecedented — you may even be able to even call yourself Knight’s friend. Names were rarely added to the List— far more frequently, they were crossed off.

Feinstein had landed on it by luck.

Two years before that contentious season, Feinstein never got more than Knight’s answering machine. But when he was writing for The Sporting News he got his opportunity.

While walking through a terminal at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, Feinstein spotted the legendary coach. Knight was sitting by himself, waiting for a friend, University of Notre Dame coach Digger Phelps, to pick him up for a golf tournament.

Feinstein did not hesitate to walk over and introduce himself. He explained to Knight he was working on a story about his protégés and asked if Knight had time to talk with him.

“What else do I have to do?” Knight replied.

It took Phelps another half hour to show up, so the two sat there talking. Knight told story after story about Mike Krzyzewski, David Bliss, Bob Weltlich and Gerry Gimelstob, all of whom had left Knight’s staff to find varying levels of success.

After the story ran, Feinstein received a note in the mail. Knight wanted him to know how much he enjoyed the article and their time at the airport.

Feinstein didn’t know it yet, but he’d just made the List.

Two years later during the winter of 1985, working for the Washington Post, he stared at that door deep within Assembly Hall. After one final deep breath, he knocked.

Feinstein could hear a barrage of profanity from inside the office. Suddenly, the door swung open. He found himself face-to-face with Knight.

“John, would you just show up on Dean Smith’s or Mike Krzyzewski’s doorstep on a game day like this?” Feinstein recalled Knight yelling.

“Well, probably not,” Feinstein replied. “I figured if I called, you’d probably say no.”

Knight laughed, then invited Feinstein into the coach’s locker room, or “The Cave.” Feinstein explained why he was there: The Washington Post wanted to know why the Hoosiers were in a tailspin, and he was the reporter on staff who knew Knight best.

Feinstein came with no agenda, no planned story. He just wanted access.

“Stick around,” Knight replied.

***

The door to the hotel room slammed shut as Feinstein and Krzyzewski left.

“Are you out of your fucking mind?” Feinstein remembers Krzyzewski saying.

This wasn’t the first time Feinstein heard this response to his new idea. It was an idea for a book following Knight, and every time he asked someone about it, this was the reaction.

For those who knew Knight, their concern wasn’t whether Feinstein would have a good book — that would be the easy part. The idea was brilliant: Spend an entire season with Knight and the IU basketball team, watching the inner-workings of one of the most demanding college basketball programs in the country.

Their concern was whether Feinstein could survive the winter.

He’d made it through those two days in Bloomington, there to chronicle the Hoosiers for the Washington Post. For 48 hours, Feinstein had a front-row seat for the intensity and genius the General carried himself with.

During those two days, Feinstein was there in the locker room as Knight built his team up before taking on Illinois, and he was there a few hours later when Knight yelled at them after a 16-point loss. He spent the entire next day with Knight, watching practice, studying film and grabbing a meal with him, trying to crack the code of IU’s woes.

The problem? Knight couldn’t figure it out either.

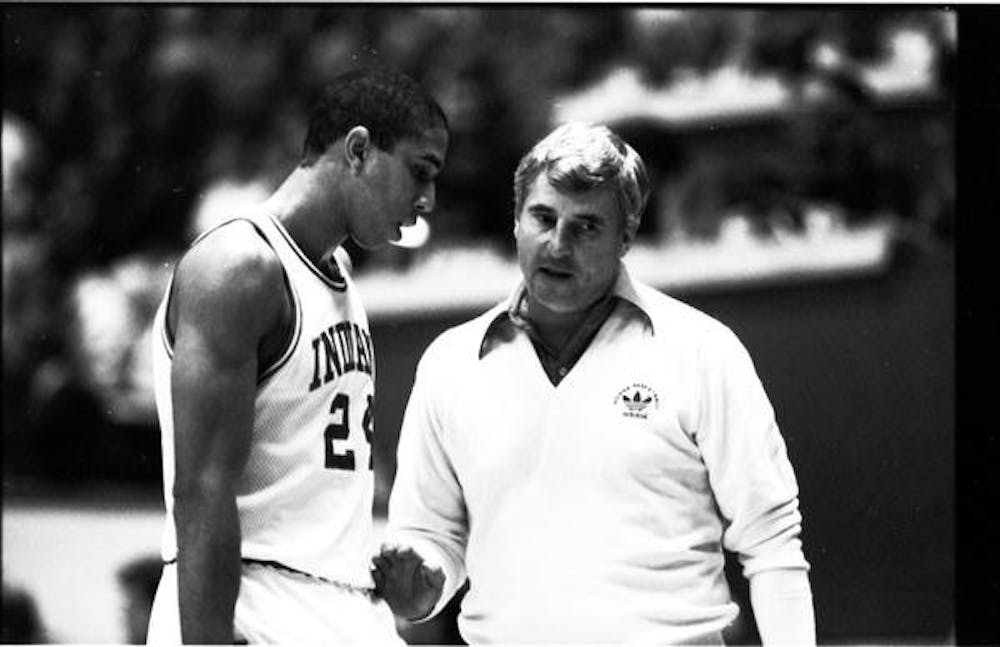

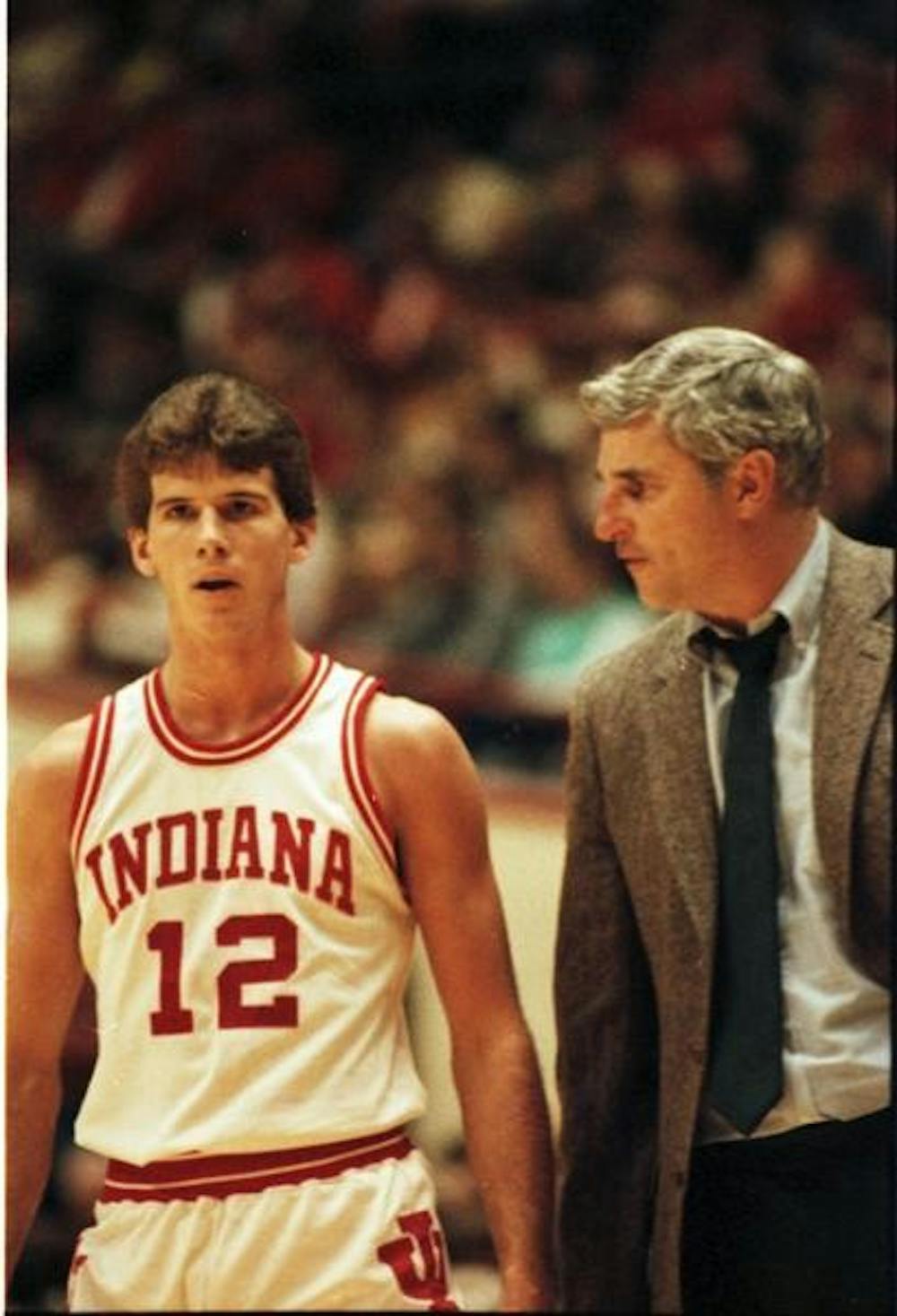

Bob Knight coaches inside the huddle Dec. 13, 1985, during a game against Louisiana Tech University at Simon Skjodt Assembly Hall. The Hoosiers would go on to end the season as a No. 3 seed in the NCAA Tournament, where they lost in the first round to No. 14 seed Cleveland State University.

As Feinstein flew back to Washington, D.C. on Saturday — missing one of Knight’s most memorable outbursts, the infamous chair toss in a loss to Purdue — he came up with the idea which would become the best selling sports book of all time. What if he took those 48 hours of access and experienced it over an entire season for a book?

A month later, at the Final Four, Feinstein proposed the idea to Knight.

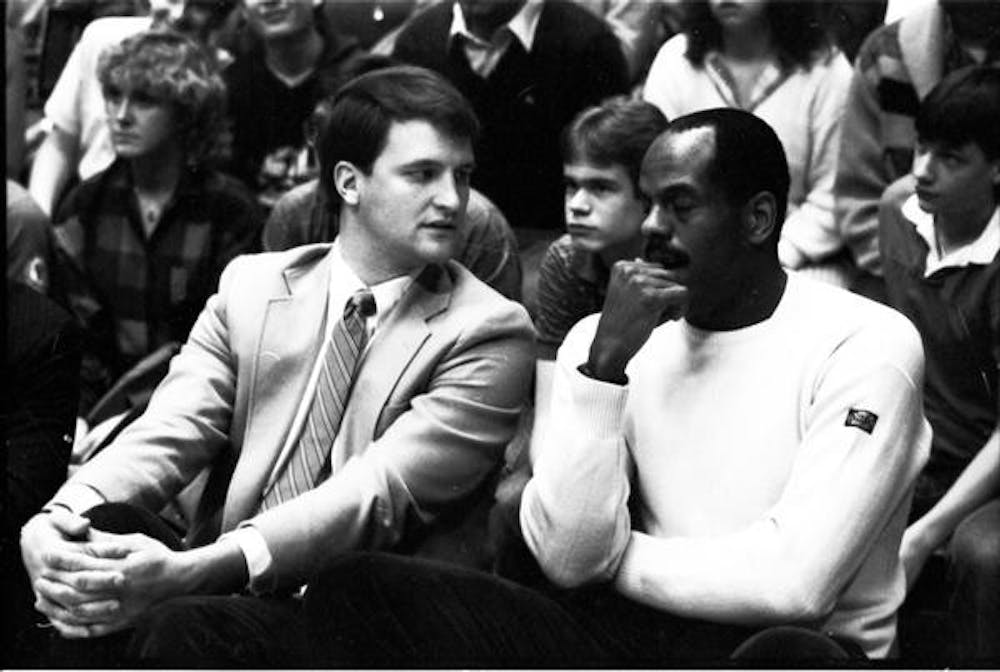

He sat in a hotel room with Knight, Krzyzewski and Pete Newell, one of Knight’s mentors, and pitched the book. While Feinstein walked Knight through the idea, the coach’s intrigue in the book grew. The others listened in stunned silence.

By the end of the conversation, Knight was sold. “A Season on the Brink” was born.

Feinstein left the hotel room with a grin stretched across his face. Krzyzewski followed.

“You’re volunteering to spend a winter with him?” Krzyzewski asked.

“Mike, you played for him for four years,” Feinstein replied, confused. “You coached for him for a year.”

“Yeah, I needed a place to go to college,” Krzyzewski said. “Last I looked you’ve been to college. I needed a job, the last I looked you have a job.”

“You’re out of your fucking mind.”