The flier for the party featured Freddy Krueger and the blood-tipped blades at his fingertips. The IU fraternity Halloween bash was branded “A Nightmare in B-Town.”

At the bottom of the ad was a promise: “Security strictly enforced.”

Saturday, Oct. 27, around 400 college-aged partygoers, many of them IU students, wove in and out of the Eagle’s Nest clubhouse near Lake Monroe.

The rituals of a frat party held true. Tequila breath and pheromones swirled in the air. Packs of cats and devils giggled in the bathroom, sharing tubes of mascara.

Alcohol surged through bloodstreams. Skeletons grinned at one another. Heels click-clacked on tile.

Then, gunshots.

Inside the crowded venue just after midnight, a man pulled out a semi-automatic handgun and shot one partygoer eight times. Two other men were shot once each.

At the Emergency Dispatch Center, call screens began to light up.

“I think someone’s dead,” one caller said.

A jumble of IU students and other partygoers scattered around the body of 21-year-old KeMontie Johnson. At least 100 people were there when the gunfire began.

Six months have passed since that night. There are no suspects. There have been no arrests.

No one has stepped forward to identify the shooter.

People aren’t shot dead at IU fraternity parties. Administrators, professors and students alike can’t recall anything even close.

Any kind of murder is a rarity in Bloomington, and unsolved cases are even more scarce.

Over the last 10 years, the Bloomington Police Department has investigated 24 murders. Four remain active.

The Indiana University Police Department has not faced a murder since 1995.

The Monroe County Sheriff’s Office handles about two each year. They’re usually more clear-cut. This is different.

***

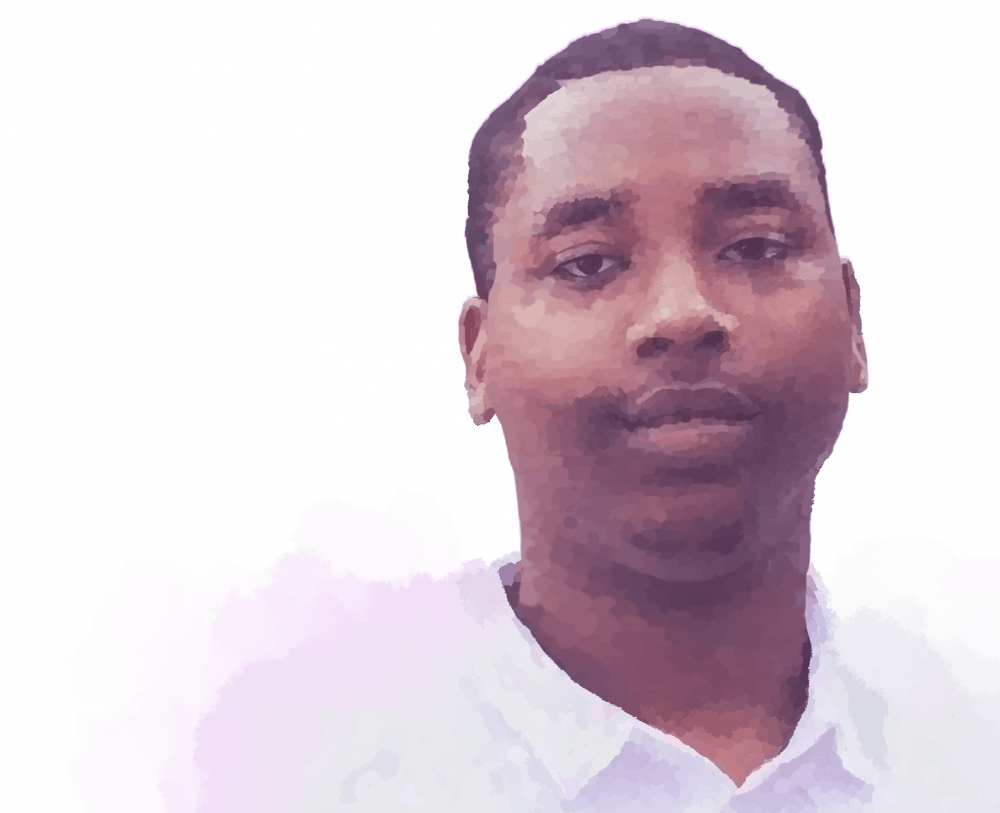

KeMontie “KJ” Johnson wasn’t an IU student, but he lived in town and worked at Kilroy’s on Kirkwood. He belonged to the Bloomington community.

He was a football star at Lawrence North High School in Indianapolis, which he graduated from in 2016. He started a clothing company called Silent Hustle, which sells hats, sweatshirts and other apparel. He was a member of 28 Way, the party planning group that collaborated with the historically black Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity to throw “A Nightmare in B-Town.”

His death rocked IU-Bloomington’s black community, which makes up about 5% of campus, according to university diversity data.

Rayshawn “Ray” Walker was shot once in the head. Though he was listed in “massively critical condition” for weeks, police said he has since returned to his home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where he is recovering.

“Happy 20th Birthday To me...” he wrote in a Facebook post on Feb. 9. “I'm truly bless to see another 1 🎉🎊.”

***

Police have been piecing together the night of the shooting for months. Just past midnight, they say, KeMontie found himself caught in the middle of a fight.

Officers said they believe the fight was over a woman, and KeMontie was trying to break it up. As the fight escalated, members of party planning group 28 Way began clearing the venue.

One of the four unarmed security guards at the event called 911. He sounded composed.

“Hey,” the call began. He told the operator 10 or 15 people were fighting in the parking lot — a standard call for a standard night on the job.

One IU student spoke to the Indiana Daily Student under the condition of anonymity. She fears retaliation from the shooter since there have been no arrests.

Advertisement

She remembered primping in the bathroom with friends that night.

Drunk on tequila and Halloween, they stumbled out, tittering about how the men were fighting over something.

Thirty seconds into the first 911 call of the night, the security guard’s voice grew panicked.

“Now we’ve got shots fired,” he yelled. “Shots fired.”

He told the operator hundreds of people were still there, screaming and spilling out of the building. They dropped to the floor. Some were trampled and bruised as everyone pushed toward the exits. At least one woman suffered a panic attack. The guard asked the operator for a medic.

“Two down,” he said as the bodies came into view. “Unresponsive. Both head wounds.”

“One of my boys just got shot,” another caller told a different operator. “My boy just got shot.”

The woman who spoke with the IDS ran by a blood-covered man who was begging anyone to take him to the hospital. She piled into the backseat of someone’s car with too many other people as they watched ambulances and police cruisers tear by.

“Oh, fuck,” a caller said over and over. He choked on sobs.

“What’s your name?” The operator asked. The call dropped.

“There’s been a shooting at Eagle Pointe,” another man said on the phone.

“What is your name?” The operator asked.

“I can’t tell you that. I’m sorry.”

***

In the days after the shooting, police began to realize this wouldn’t be a standard investigation.

Some witnesses said they had been drunk and wouldn’t recognize the shooter. Others just didn’t want to be attached to the event. Mostly, fear silenced young adults.

Monroe County Sheriff Brad Swain hoped that would change.

“There’s a potential for it hampering the investigation when people with useful information choose not to come forward,” Swain said.

The woman who spoke with the IDS described watching the sparks fly from the shooter’s gun. She saw him.

She didn’t know the gunman, though. She said she couldn’t pick him out of a lineup.

She watched his victims fall to the ground. She ran, clambering over other partygoers’ heads and backs.

She panicked.

He's going to shoot me in the back, she thought.

Of the dozens of partygoers the IDS reached out to, she was the only one who agreed to an interview.

One man told a reporter reaching out on behalf of the IDS he saw the shooter’s face.

Asked why he wouldn’t talk to police, he said, “I ain’t no snitch.”

Black Americans hesitating to talk to police is nothing new. Frederick Shenkman, a University of Florida professor who has taught and worked in the areas of race relations and law enforcement for more than 50 years, says it’s grounded in four centuries of black people being enslaved and othered in America.

“There is mistrust and distrust of the police,” he said. “This is not exactly irrational.”

He said that kind of wariness is difficult to shake when people have grandparents who lived in a world where police existed to harass — not protect.

“If we don’t take care of each other, who will?” Shenkman asked.

Whatever happened at that party, many people don’t want to talk about it. Police feel some witnesses are withholding information. Media requests for any information — even a sentence or two on who KeMontie was — go ignored.

This isn’t surprising, Shenkman said. History has led Bloomington to this moment of silence.

“This is a lightning rod that has brought lot of different things together,” he said. “These things don’t fall out of the sky.”

Jeannine Bell, an IU Maurer School of Law professor and scholar of policing and hate crime, agreed.

“Minorities and whites don't feel the same about law enforcement officers, even in this town,” she said. “Bloomington is not immune to the problems that exist in other cities.”

But maybe no one recognized the man who fired the gun over and over. If the shots were back-to-back, gunfire might have lasted just seconds. Maybe witnesses are fearful of being punished by the university. The party, after all, wasn’t registered with IU and led to the deferred suspension of Kappa Alpha Psi. Maybe the trauma of that night is too difficult to relive in statements and interviews. Maybe no one recognized the shooter. Maybe alcohol blurred the memory of him.

Whatever the case, the reasons could be tied up in a lot of things.

They’re tied up silence — codified or otherwise.

***

Freshman Alice Aluko was walking home from a different Halloween party that night when she heard about the shooting at Eagle Pointe. She had nearly gone to that party. She had friends there.

She finished her walk home in stunned silence.

The disconnect between IU’s black community and the rest of campus crystallized in front of Alice.

“I just remembered looking around at the other students, the white students, coming back from other parties still happy,” she said. “I felt like I was in the Twilight Zone.”

Beyond the obligatory press release, hardly anyone would talk about that night.

The IDS reached out to dozens of people who attended the party, family members of the deceased and injured, members of various campus groups and IU administrators familiar with the situation in reporting this article.

Nearly all who were contacted did not respond, declined to comment or would not speak on the record.

A rush of anonymous tips flooded the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office in the days following the shooting, but police have no witness willing identify the gunman under oath.

Quickly after the news broke, the sheriff’s office said there was no safety threat to Bloomington. The gunman was likely from out of town. Months later, people are telling detectives they still won’t talk out of fear of retaliation.

“They're just generally afraid. ‘If someone would be willing to do this to KeMontie, would the same person be willing to find me and do this to me?’” Detective Mason Peach said.

Peach is the lead detective on the case. He’s been with the Sheriff’s Office for about 13 years. He was on scene after the party cleared out and police tape went up.

He said members of Kappa Alpha Psi have been more than cooperative with the investigation. Others, he said, have been less accommodating.

People haven’t told him they won’t talk because they aren’t snitches, but he gets the feeling that’s what they’re thinking. His gut tells him some witnesses aren’t telling him something. They say they just don’t want to get involved.

Police are looking into multiple people. But they can’t develop a suspect on whispers and rumors.

Advertisement

“This could break tomorrow, or it might be weeks from now,” the detective said. That was in November.

In the months that followed KeMontie’s murder, the tips slowed to a stop.

“The general consensus is still people just don't want to be involved in this,” Peach said in February.

Almost six months after the party, he said it might be time for investigators to start retracing their steps. The sheriff’s office is planning to start re-interviewing potential witnesses, hoping something new will shake loose as the shock and grief subside.

Peach has always maintained his department will close this case. He never hesitates to answer that question. He just has a feeling, he says, that someone will come forward.

“I think at some point someone is going to — for lack of a better word — be brave,” he said.

***

Hours after the gunfire, police tape crisscrossed the tidy clubhouse, with its expansive, shining windows and its faux-rustic dance floor.

A few security cameras pointed out at the surrounding empty roads. Their footage, infrared and grainy, wouldn’t be much use to investigators. None pointed toward the dance floor.

By the time police arrived, pieces of costumes lay strewn about the venue. Halloween was still days away.

Less than two days after KeMontie was pronounced dead, a vigil for him drew a crowd of about 300 to IU’s Showalter Fountain.

The fountain was silent, and the air was cold as mourners clutched dripping candles. One woman burned sage.

“This cannot end tonight,” someone said. “Love is the way. Love is power.”

At the vigil, one of KeMontie’s friends crumpled to the ground. Sobs wracked his body.

28 Way, the group that collaborated with Kappa Alpha Psi to plan the Halloween party, threw a skate party in KeMontie’s honor the night before Thanksgiving. Fliers for the event bore an illustration of KeMontie gazing wistfully toward the sky. “#stopthegunviolence,” they read.

There were marches against gun violence and more merchandise was released in KeMontie’s memory. 28 Way continued to plan events.

KeMontie’s company Silent Hustle released a shirt bearing his haloed face, finger pressed to his lips. “SHHHH!” it read.

On the six month anniversary of his death, KeMontie’s mother posted on her Facebook page.

“It’s a difference between snitching and doing the right thing,” she wrote. “Know the difference.”

Add your voice to the conversation. Write to us at letters@idsnews.com.

This story was reported over the course of six months by listening to 911 calls, sifting through social media, reading police reports and extensively interviewing officials and others involved.

The Monroe County Sheriff’s Office asks that anyone with information related to this case contact its investigations department at 812-349-2727.

Like what you're reading?

Support independent, award-winning student journalism. Donate.

© Indiana Daily Student

Back to idsnews.com or top of page