INDIANAPOLIS — The kids felt it first. That day, when the governor declared refugees like them unwelcome, fear pulsed through their schools.

Rama, the 15-year-old, heard it in her classmates’ voices when they blamed Muslims, saw it when they pointed at her headscarf. Rakan, her 13-year-old brother, was caught off guard when a group of boys approached him in the hallway.

“Are you from ISIS?” they asked him. He shook his head and shuffled away.

Like the rest of their family, the two teenagers knew about the terror in Paris the previous Friday — the bombings and gunfire that had left more than 100 people dead. They knew that ISIS had claimed responsibility for the attacks and that a fake Syrian passport had been found among the destruction.

The following Monday evening, when the Batman family heard that Gov. Mike Pence was blocking Syrian refugees from entering Indiana, their small apartment fell silent.

Ten seconds passed. Fifteen, then twenty. Marwan, the father, was the first to speak.

“Call?” he asked in his broken English, holding up a cell phone. “Call?”

Marwan didn’t know the governor’s name and didn't understand that getting him on the phone would be almost impossible. Over the rims of his glasses, he looked at his wife Lona, at Rama and Rakan, at his two youngest daughters chasing each other up and down the staircase.

If he could just talk to the governor, maybe Marwan could tell his family's story. Maybe he could help the man understand.

***

The Batmans are among a handful of Syrian families who have fled civil war and settled in Indiana, joining about 2,000 Syrian refugees living across the United States. Since the terrorist attacks in Paris, they have been swept up in a national wave of paranoia and hatred.

In Chicago, two men were asked not to board a plane after they were overheard speaking Arabic. Human feces and pages ripped from a Quran were thrown at the door of a Texas mosque. A few hours’ drive from that mosque, protesters outside an Islamic center carried picket signs and 12-gauge shotguns.

As outrage grew, an Indianapolis refugee volunteer told the city’s small community of Syrians to stay in their homes. “People are angry,” she warned them. “I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Citing concerns of terrorism, more than half the country’s governors announced plans to oppose or block Syrian refugees from settling in their states. Pence was one of the first.

“Indiana has a long tradition of opening our arms and homes to refugees from around the world," Pence said in a statement. "But, as governor, my first responsibility is to ensure the safety and security of all Hoosiers.”

When Pence made his announcement, a new family of Syrian refugees was scheduled to fly into Indianapolis the next day. They never made it. The couple and their small child were rerouted to Connecticut, where the governor publicly welcomed them and bashed Pence’s decision.

“This is the same guy who signed a homophobic bill in the spring, surrounded by homophobes,” Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy said. “So I’m not surprised by anything the governor does.”

As masses of Syrians huddled outside European borders and in cramped refugee camps, they became the central figures in a debate over the soul of America. Would a nation founded by refugees now turn them away?

Politicians labeled them terrorists-in-wait, saying the United States’ intensive screening process couldn’t catch everything.

“Highly concerning,” said Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker.

“It is clear that the influx of Syrian refugees poses a threat,” said Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker.

“I will do everything humanly possible to stop any plans… to put Syrian refugees in Mississippi,” said Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant.

Republican presidential frontrunner Donald Trump suggested the refugees could be a “Trojan horse” for terrorism and proposed barring all Muslims from entering the country. Fellow candidates Jeb Bush and Ted Cruz offered plans to accept only Christian refugees.

President Obama condemned the blockade, calling it “shameful” and “not American.” He declared the United States would continue to accept refugees.

As America argued, the flood of people trying to escape Syria continued. Ten million Syrians have been forced out of their homes as casualties of an ever-escalating civil war. Of those, more than 4 million have fled the country and registered as refugees.

Gov. Mike Pence

This summer, President Barack Obama pledged to take in at least 10,000 Syrian refugees over the next year. The country had made little progress on that plan.

The United Nations has recommended more than 22,000 Syrian refugees for resettlement in the United States since 2013. After a screening process that can take as long as two years, about 2,000 have been accepted.

The Batmans were among the first Syrian refugees to settle in Indiana. Since their arrival in November 2014, they had been navigating a world they barely understood: learning English, starting school and paying bills while the country decides what to do with them.

When they arrived, everything was new. Rakan knew his last name — Batman, like the superhero — was famous in America, but not much else.

The family had mapped out their future: apply for green cards, send Rama and Rakan to college, become American citizens, get the rest of their family out of Syria. Go back only after the war.

After American leaders turned their backs on refugees like them, that future felt uncertain.

***

Marwan worked in the back of Al-Rayan Restaurant, a Middle Eastern diner on the west side of Indianapolis. Slicing another piece of fat off a chicken kebab, he wiped away a line of sweat on his forehead. His thoughts traveled 6,000 miles away to his own restaurant in Syria, where he stood at the front, never hidden in a corner.

He was 47, a short man with gray hair and fingers scarred from an accident with a meat grinder. He smiled more often than not. He knew just a few words of English, but laughed at almost everything he heard anyway. For now, he was making just enough to keep his family going. But he swore he would be friends with President Obama before the year was out.

In Syria, he was owner, operator, host and head chef. In America, he was an $8.30-an-hour laborer, an inglorious step down that gnawed at him.

As he sliced off another piece of fat, Marwan sighed and started to sing, filling the empty restaurant with the off-key warbles of “Ebatly Gawab,” an old Syrian love song.

I have a God, who knows me…

From the pain he shields me…

I will be patient all the time, and endure my pain.

Marwan’s songs were his connection home. As he sang, the chaos around him faded away. He was back in Homs, the ancient city where life was “like a dream,” he said. He saw the small arenas where he once played soccer, his mother’s house, his own restaurant.

“Syria, Arabic restaurant, chef,” he said. His eyes flitted back and forth as he tried to find the words in English. He wanted to join Lona at her weekly English classes, but couldn’t afford the time away from work. For now, the restaurant would have to be his classroom. “Work good, money good,” he said, smiling at the memory. “And then…” He made a fist, lifted it high above his head and brought it crashing down on the cold metal table. The table wobbled.

An explosion. His restaurant destroyed, blown to rubble with the rest of the city. A comfortable life ripped off its foundations.

“And then…”

Then, he started over.

***

When the Syrian army arrived in Homs, the protesters welcomed them with flowers.

Peace, peace, they chanted. Army and people are one.

The soldiers answered with bullets. In 2011, Homs became the “cradle of the revolution,” and the ancient city transformed into a center of Syrian violence.

When summer came, Marwan and his brothers huddled in their mother’s home. They followed the news on a cell phone and played cards as bullets flew over their heads.

Outside, a dozen snipers sat on top of an ancient Syrian castle, rifles pointed at the street below. They shot immediately and indiscriminately, killing whoever set foot outside at night. “It was illegal for a human to move,” Marwan said.

As the sun fell one evening, Marwan slept in a front room. He awakened to the sound of sniper fire and bolted to the door, where he found Borhan, his older brother, about to step outside to find bread for the family.

Marwan grabbed his hand.

“Stop, don’t go!” he pleaded. “It’s not safe.”

Riding past on his bicycle, a neighbor noticed the door open and stopped to say hello. A sniper fired. The young newlywed fell to the street as Marwan pulled his brother inside.

Airstrikes from the Syrian regime became routine. Parents opened the door to find their children dead on the front stoop.

Marwan let winter come and go, and decided to flee in June 2012. Choosing the risk of daylight over the nighttime snipers, the family piled into a minivan and handed the driver $500 to take them into Lebanon.

In Lebanon, they floated through life for two years. Marwan couldn’t find work, so Lona sold her jewelry to pay for rent and food.

After three interviews with United Nations screeners, they were granted refugee status and assigned to the United States, where they would face what’s been called the world’s most thorough vetting process.

Marwan and Lona sat through three interviews with American officers, answering the same questions each time. No, they repeated, they weren’t planning a terrorist attack. They didn’t carry weapons. They weren’t planning to commit suicide.

“They asked how many breaths I took a day,” Marwan said, opening his eyes wide in exaggeration. “It’s harder for Syrians.”

In Lebanon, they were fingerprinted and photographed, given a full medical checkup, tested for infectious diseases and sent to a class on American culture. Their files were delivered to Homeland Security officials in the U.S., and they waited.

Then, in January 2014, Marwan’s phone rang. A U.N. worker told him that his family had been accepted into the United States and would move by the end of the year.

In Syria, they knew almost nothing of America. “America bad, Syria good,” is all anybody ever told them, Marwan remembered. Their knowledge was limited: Marwan liked cowboy movies, NBA basketball and reruns of “The Love Boat.”

They had never heard of Indiana.

Ten months later, they boarded a plane in Lebanon, carrying eight suitcases stuffed with clothes. They left everything else behind. “Our pictures,” Lona said. “Everything.”

After 17 hours of flights, the Batmans landed at Indianapolis International Airport in a chilling November rain. A volunteer worker met them at the airport with winter coats for the kids, who were dressed for the warmth of Lebanon.

As they pulled on coats and collected their bags, Marwan slipped through a door and stepped outside. He pulled a pack of cigarettes out of his pocket and lit one, shivering in the cold as their new life began.

***

“The governor of intolerance,” the newspapers called him. “Small-minded.” Accused of preying on fear for political gain.

“Pence seems determined to solidify our state’s reputation as unwelcoming bigots,” one editorial wrote.

After Pence’s announcement, the governor became a national target. In defense of his decision, Pence sent a letter to the state’s Representatives and Senators. Indiana would continue to accept refugees, he said — just not Syrians.

Critics questioned whether a governor has the power to block refugees from a state in the first place. The Refugee Act of 1980 gives no specific authority to states, and the Obama administration has called refugee resettlement a federal issue.

The ACLU filed a lawsuit against the governor on behalf of Exodus Refugee Immigration — the agency that helped the Batmans settle in Indiana. The group called Pence’s decision an “unconstitutional bluff” and told him Exodus would continue to bring Syrian refugees to Indiana.

“He does not have the power to pick and choose between which lawfully admitted refugees he is willing to accept,” the ACLU’s Judy Rabinovitz said in a statement. “Singling out Syrian refugees for exclusion from Indiana is not only ethically wrong, it is unconstitutional. Period.”

***

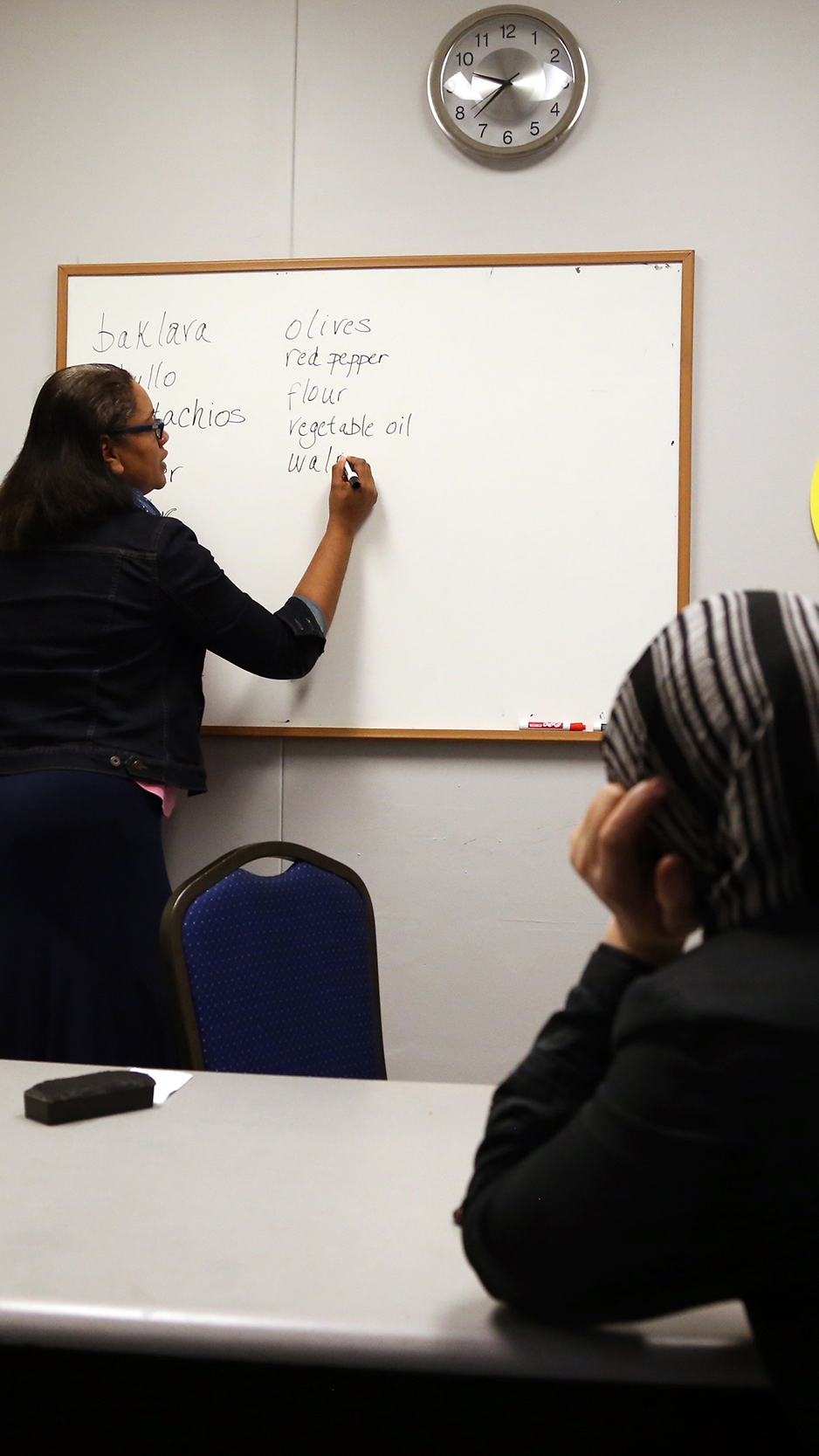

Squarely in the center of the hostility, the Batmans tried to shield themselves. Marwan continued to work six days a week. Lona went to English class every Saturday and studied on her own twice a day. They asked about getting their parents out of Syria but were told there’s little chance.

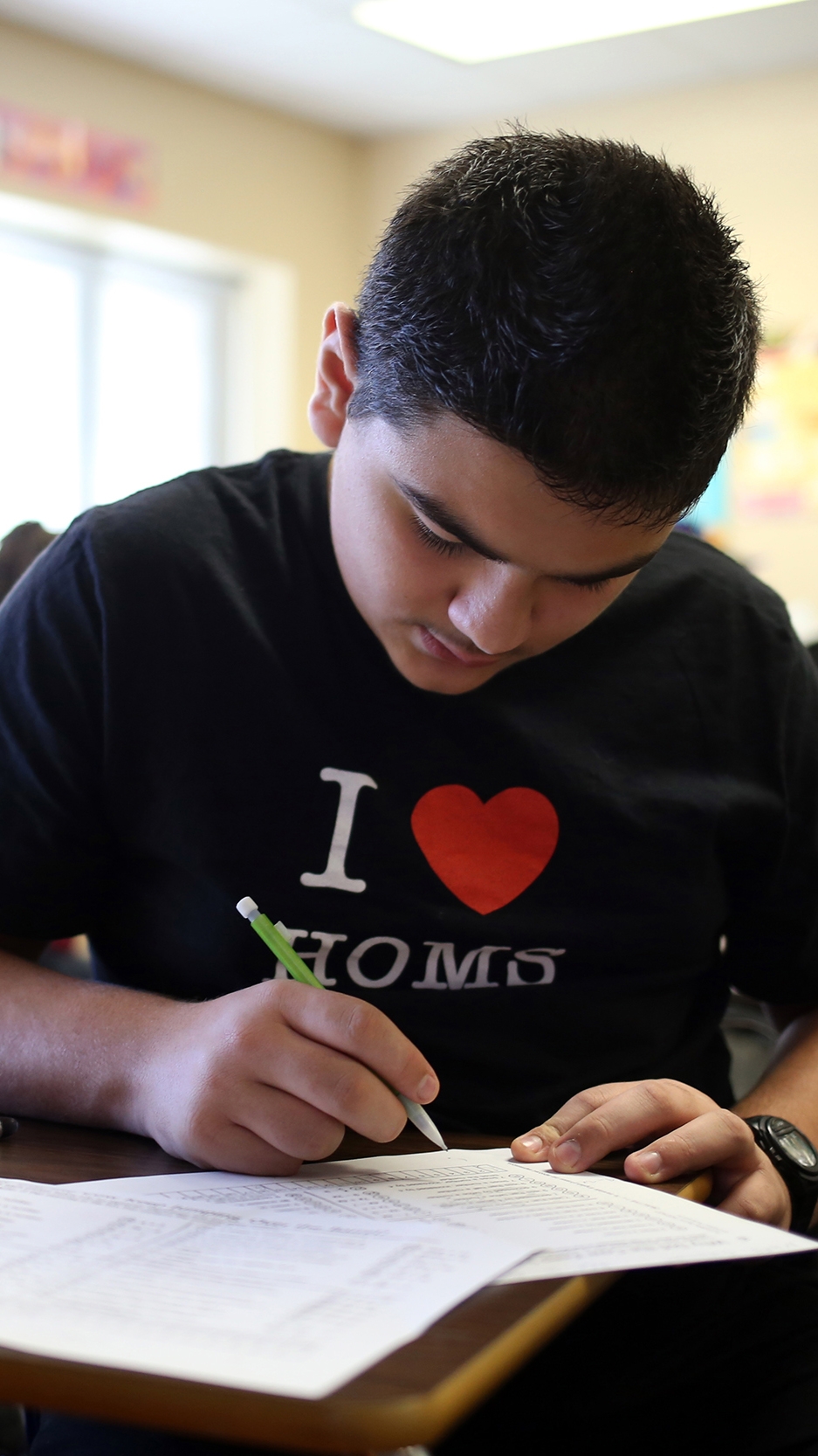

Rakan, the seventh-grader, has kept to himself since the announcement. He didn’t speak up when his teachers discussed the Paris attacks, and lowered his eyes when classmates talked about ISIS.

“I was scared,” he said. “Maybe they call the government.”

One recent Monday morning, Rakan limped through the hallways of Belzer Middle School. His 13-year-old hips were sore, he said. The day before, he felt like running, so he did, dashing off in his jeans and not stopping for four hours.

As he headed for first-period algebra, he walked side-by-side with Faris, his best friend and the school’s only other Arabic-speaking student. The school gave them identical schedules, and the two of them spend most of their school days in a silence that breaks only when a teacher asks Rakan to translate for Faris or a classmate shows off the Arabic words Rakan taught them.

As they walked with their heads down, a short boy rushed in front of Rakan and turned to face him. The boy, one of Rakan’s few friends at Belzer, worked to keep himself from laughing as he took a deep breath.

“Go fuck yourself!” he screamed in Arabic. Rakan smiled wide and raised his hand for a high-five. He’s taught them how to say “hello,” too, he promised.

In every class, he sits near the teacher’s desk. He understands about half of what they say and falls behind his classmates almost immediately. One teacher said his job is just to get Rakan talking, and any material he learns is a bonus.

So Rakan coasted through his school day, seven hours of head nods and smiles. He finished less than half of a worksheet asking him to translate English sentences into mathematical expressions. It took him a dozen tries and almost 10 minutes to count $2.77 of American money. In a lesson on the history of Islam, a teacher flashed a picture of Abraham on the screen, and Rakan laughed. “Abraham doesn’t look like that,” he said, pointing at the photo of an old white man with a long beard.

A language arts teacher pulled Rakan and Faris into the hallway to practice reading aloud. The boys stared at creased copies of “A Long Walk to Water,” a novel about Salva, an 11-year-old Sudanese refugee.

“We talked about refugees last time,” the teacher told Rakan. “Salva is a refugee. Do you remember why?”

Rakan didn’t look up from the book. “Because he had to leave Sudan.”

“Do you know why?”

Now he lifted his eyes. “War.”

Rakan didn’t stop at his locker as he rushed out the door. It has sat empty for months. Somebody gave him the combination a long time ago, but he forgot and wasn’t sure how to ask for it again.

***

***

Nothing in the Batmans’ apartment matched. The walls were sparse, the furniture donated. Marwan’s wages and a small package of government benefits didn’t allow for much decoration.

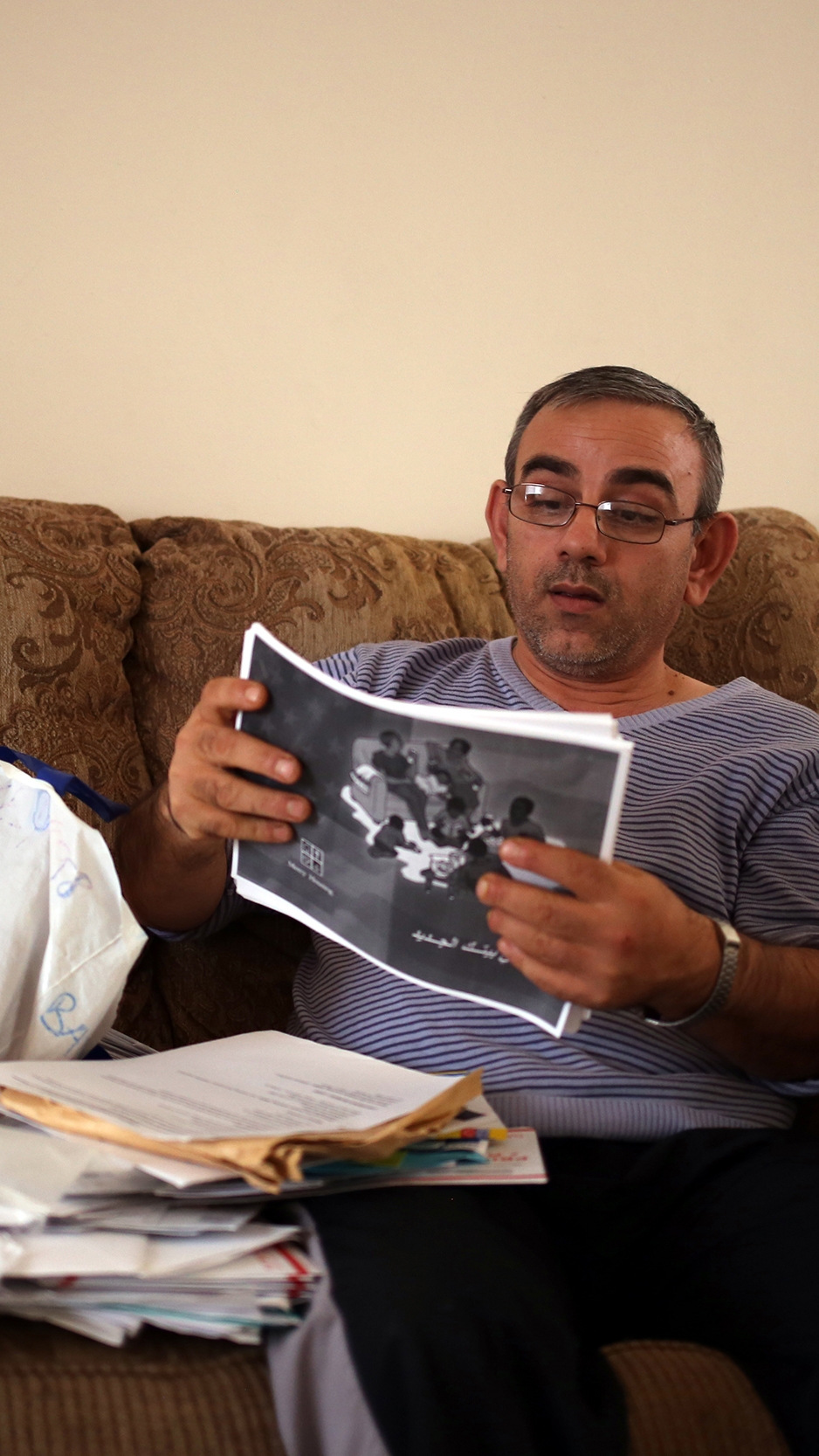

Marwan pulled the drawstrings on a bulging plastic bag and dumped half of it onto the couch. Three years of paperwork came spilling out.

Unopened envelopes from official-looking addresses. Forms — some filled out, others left blank. A scan of four stents in Marwan’s heart. Medical records. Immigration paperwork. Bills. Almost everything in English.

“Paper, paper, paper, paper,” Marwan said, eyes bulging as he filed through. He held a housing brochure at an arm’s length, then realized it was upside-down. He flipped it over.

He needed their doctor’s name. All six of the Batmans needed vaccinations, and time was running out to get them. Their final green-card interview was less than three weeks away.

If Marwan didn’t get his family’s paperwork filed by then, they would become unauthorized aliens in the U.S. Refugees can’t be deported, but they would lose their rights in the country, including Marwan’s right to work. Everything would unravel in a moment.

He found a prescription he thought might have the doctor’s name on it. “Dr. Waller,” he read aloud. “Family doctor? I don’t know.” His wife didn’t remember, either.

He put the prescription on the table and turned back to the pile. Eventually, he found Dr. Waller’s name again, on a diagram of Marwan’s heart.

“Heart doctor,” Marwan said, pointing at the surgical scar on his chest. “Very nice.”

Very nice, but not the right doctor. Marwan shuffled the prescription back into the pile and kept looking.

***

Marwan, Lona and Rama crowded around a small desk at Exodus Refugee Immigration, shifting in their cold wooden chairs. Behind the desk, Megan Hochbein flicked on her computer and pulled out a thick file.

“So,” she said through an interpreter, “We are filing for green cards today.”

Lona pulled out a notebook. Marwan fiddled with a pack of cigarettes in his pocket. Rama sent one last text. The other three children were left at home — she was the only one old enough to fill out her own application.

“There’s going to be a lot of paperwork,” Hochbein said. “At one point, there’s going to be a long list of kind of awkward questions we need to ask.”

She ran through a list of questions, reading each one in English before an interpreter relayed them in Arabic.

She asked if they’ve ever prostituted themselves; if they’ve trafficked drugs into the U.S.; if they’ve participated in a genocide; if they intend on practicing polygamy, which made Marwan giggle.

“Have you ever engaged in, conspired to engage in, or do you intend to engage in, or have you ever solicited membership or funds for, or have you through any means ever assisted or provided any type of material support to any person or organization that has ever engaged, or conspired to engage in, sabotage, kidnapping, political assassination, hijacking or any other form of terrorist activity?”

All three shook their heads.

Marwan only answered yes three times. His family is on food stamps. Yes, he served in the military, he said. Yes, he received military training. Two years of required service in the Syrian air force, well before the war.

“I was a bus driver,” he said. “I was trained how to assemble and clean the weapons, but I never used it.” He explained that he spent most of his service time playing on and coaching the soccer team.

As the pile of finished forms stacked up, the meeting stretched into its third hour.

“I’m sorry; it takes forever,” Hochbein said. “All of these papers.”

While the government processed their applications, they would be called in for fingerprinting, additional interviews and, possibly, more paperwork.

Hochbein explained it could be as long as seven months before a decision was made on the Batmans’ applications, and approval wasn’t a certainty — even with clean records and a smooth application process.

“It’s not a guarantee,” she said.

When she heard they might be rejected, even after all they’d been through, Lona’s eyes went wide.

***

***

That day, as the Batmans signed more papers and answered more questions, the national debate over the fate of Syrian refugees showed no signs of settling.

Every Republican presidential candidate opposed accepting Muslim Syrians into the United States – all but two were against accepting Syrians entirely. Islamophobia was the strongest it had been since 9/11.

Another family of Syrians was scheduled to fly into Indianapolis on Monday. Catholic Charities of Indianapolis had considered defying Pence’s wishes and bringing them to Indiana anyway, so Pence met privately with the Archbishop. No exceptions, the governor said. The Archbishop said he’d consider it.

Tensions swirled around them, and the Batmans tried not to notice. They preferred to stay on the path. They were building an American life bit-by-bit.

Outside Exodus, they headed for the family’s donated Chrysler and strapped in. Marwan turned the key, and the CD player started up automatically. He tapped their home address into the car’s navigation system. Above them, an almost-full moon floated in an empty sky.

Marwan lit another cigarette and pointed the car toward home. Before they left the parking lot, he was singing again.