The Little Sister

Haley Wilson started her freshman year only a few months after the murder of her older sister, Hannah Wilson. Haley wants to be strong. But when you're only 18 and your world has cracked open, how do you know what strong is?

The freshman sits in psychology class, hidden in the back row as always, relieved that no one knows who she is. She thinks about her big sister, also a psych major, who aced the last exam of her life in this building hours before she was abducted.

On the screen, the professor shows a photo of a man convicted of a different murder. By analyzing someone’s face, he says, one can predict if that person will kill.

Haley Wilson looks at the face on the screen. She thinks about the man accused of bludgeoning her sister to death in April. She doesn’t like to say his name, but she has seen his booking photo. She becomes too nervous to pay attention and mentally checks out of the lecture.

Some people tell Haley it’s been four months since the murder and she should move on. Others say it’s too soon and she should be too grief-stricken to start college. Haley floats in the middle. Some days she tries to make sense of something senseless. Other days, she does her best not to think about the murder at all.

* * *

Most freshmen, at the start of their first semester, wonder how they’re going to make it on their own. At IU, freshmen are given pointers on how to wash bright colored clothes in cold and make it to class on time. But there’s no handbook for what Haley Wilson is going through.

Last spring, during Little 500 weekend, her sister’s murder consumed the campus. Hannah, a 22-year-old senior, went missing in the early hours of April 24 after her friends had put her in a cab home from a bar. The next morning, her body was discovered in a grassy clearing in Brown County. Police arrested Daniel Messel, a 49-year-old Bloomington man, after they reported finding his cell phone next to the body and Hannah’s blood and hair inside his car. Charged with first-degree murder, Messel is in jail and is scheduled to go to trial this summer.

An introvert all her life, Haley is starting college in the shadow of a high-profile case. She said she wants her fellow students to remember Hannah’s murder, but she doesn’t want them to walk across campus in fear. She shies from the extra attention that comes with being Hannah’s sister. But when students make dead girl jokes in front of her, not knowing who she is, she fights the urge to call them out.

After reading and watching so many news stories about the case, Haley has grown to despise the word “slain.” It bothers her that journalists who never met Hannah reported about her life and death and bungled the most basic facts. It bothers her that anybody had to write about her sister at all.

Haley wears Hannah’s old clothes, walks by the house on Eighth Street where Hannah lived during her senior year and sleeps under a blanket made from Hannah’s old T-shirts. She understands she’ll eventually have to come to terms with Hannah’s death, but she isn’t ready. Haley still talks about Hannah in the present tense.

“We’re all so focused on who she is,” Haley said. “We never focus on what actually happened.”

But every day when Haley rides the A bus to class, the distractions disappear. She stares out the window and sees Foster Quad, where Hannah lived as a freshman. She sees the limestone buildings where she sat in class and dreamed about her future. Everything her sister once experienced rushes past.

“To me, she’s just on vacation.”

* * *

Before the murder, the sisters talked every day. Normally they FaceTimed late at night. But in those last few days, Haley was a counselor at Camp Tecumseh and didn’t have good cell reception, so they texted.

Hannah was busy that week in April, too. She was about to take the final exam that would complete her psychology degree. Hannah also worried about how to give equal attention to her divorced parents, Robin and Jeff Wilson, at graduation. Haley, then a senior at Fishers High School, was helping Hannah figure out which parent should organize the post-ceremony dinner and which parent would settle for lunch the following day.

That Thursday night, Haley sent her sister a picture from camp. Hannah didn’t respond. She was probably out celebrating with her friends, Haley figured, because it was the start of Little 500 weekend and the end of her college career.

The next day, Haley texted Hannah again around noon. When Hannah didn’t answer, Haley told herself her sister was probably sleeping late.

Haley got home from camp that afternoon and took a nap. She woke to a buzzing of missed calls and texts. Hannah’s friends wanted to know if Haley had heard from her sister. They had filed a missing person’s report, which confused Haley. “Missing” made no sense next to Hannah’s name.

Then her father called.

“They can’t find your sister.”

Jeff, a physician in an urgent care clinic in Indianapolis, had left work to drive to Bloomington.

Haley called her mother, a veterinarian in Noblesville, Indiana. Robin was on her way to Bloomington, too. Robin said she felt she was driving to Bloomington to find out her daughter was dead.

Haley was sure Hannah was fine, but she resolved to join her parents. Hannah would be devastated if her little sister wasn’t looking for her.

Haley drove down with her best friend Alexis Klein. In her mind, Haley saw herself finding Hannah and hugging her in the street.

Alexis was checking the social media updates on her phone. More and more “missing” posts appeared, and Haley grew anxious. By the time she hit the traffic in Martinsville, Indiana, she was getting calls from her mother, telling her to turn around and go home. Haley kept driving. What she did not know was that the police didn’t want her on the road. They preferred that Haley wait in Fishers for a police escort.

When she finally arrived at the police station, her father was waiting for her outside. In all her life, Haley had never seen him cry. Now, he was sobbing.

“It’s not good,” he said.

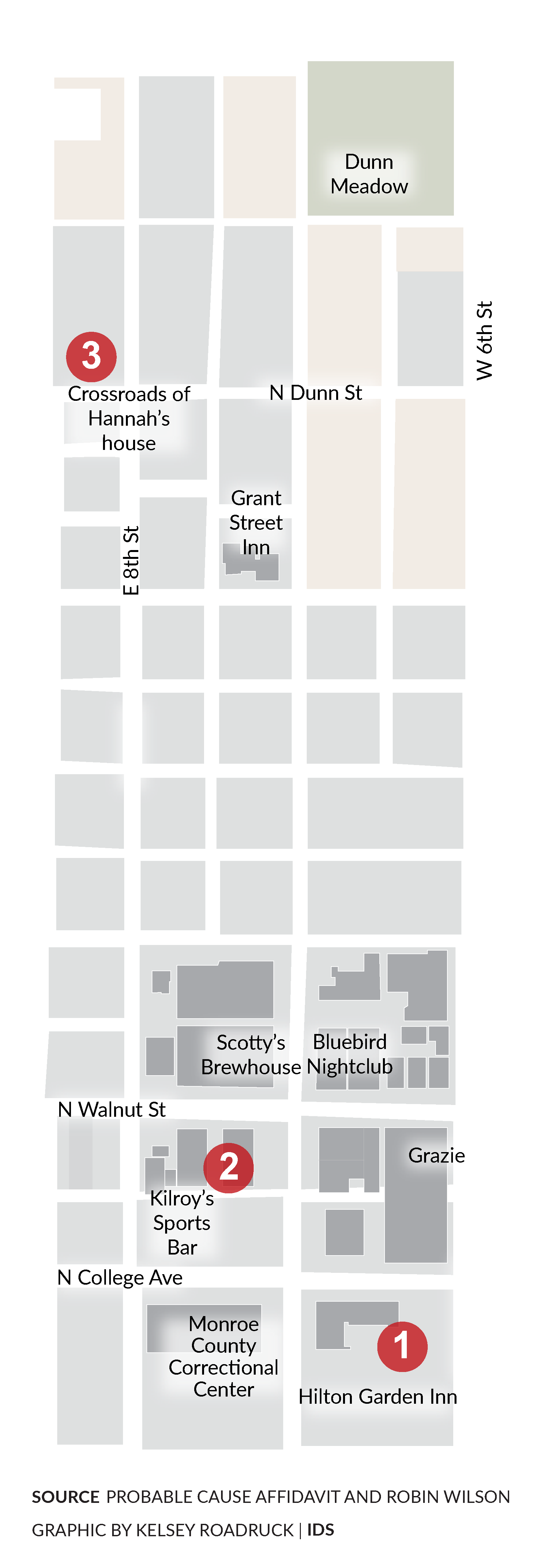

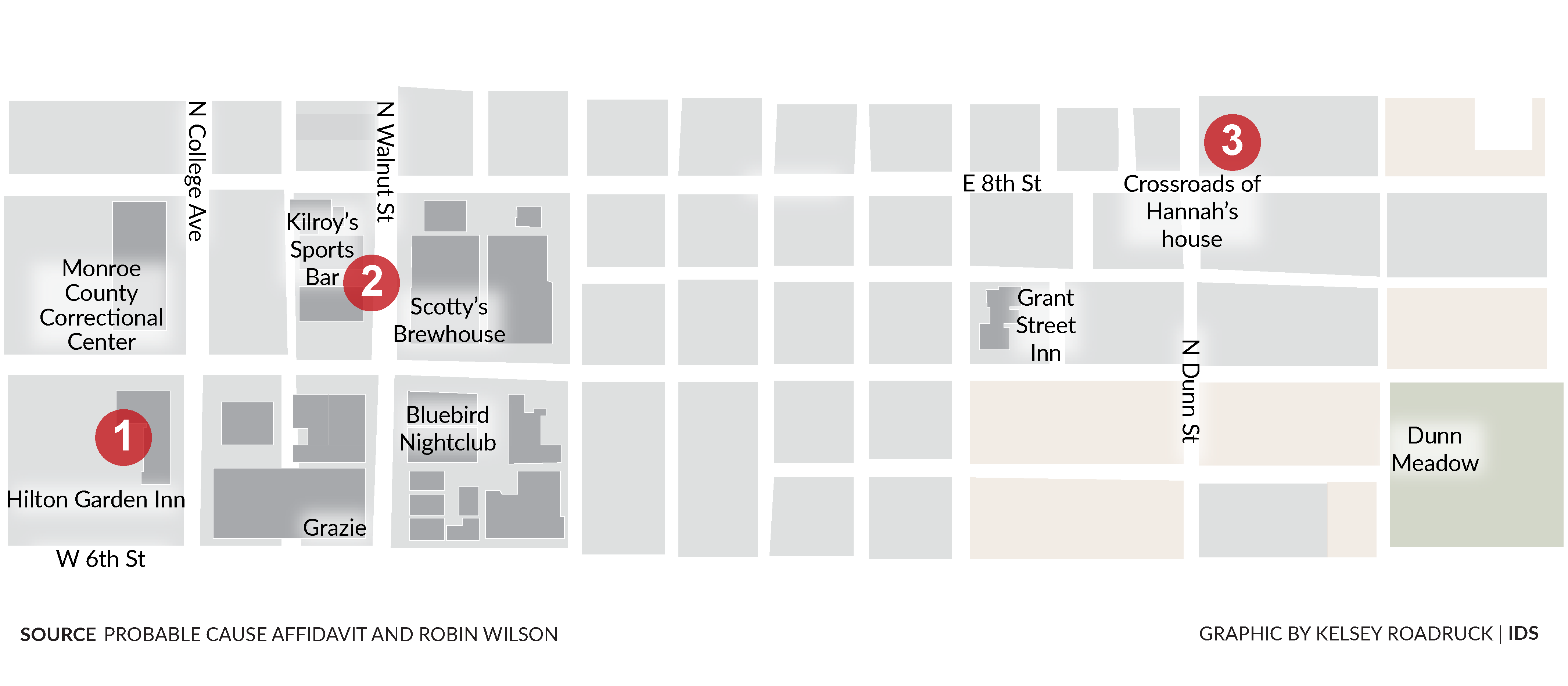

Hannah's Last Hours

The following maps a timeline of how and where Hannah spent the final few hours of her life. She remained within a half-mile radius of her Bloomington home and friends until she was abducted.

Chapter II

Haley had always been the quiet one.

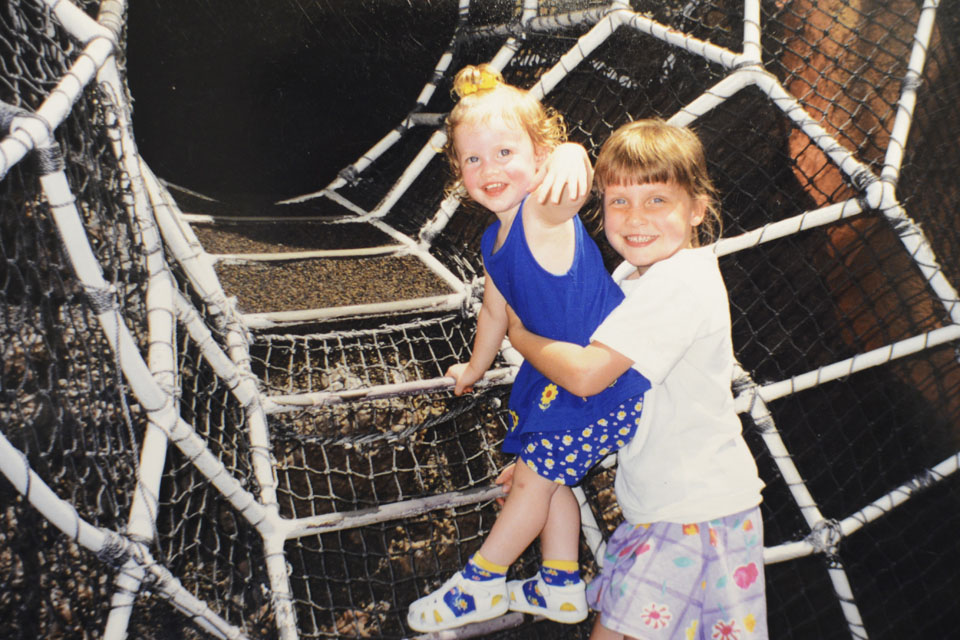

She didn’t say her first words until she was 3, her father remembers, not because she didn’t have anything to say, but because she didn’t need to talk. Hannah spoke for her.

Hannah was exuberant, loud and theatrical. Haley was reserved, cautious, shy. Hannah often directed the two of them in home movies, and she usually casted her little sister in the supporting role and herself as the star. Hannah would invent songs on the piano and get Haley to sing along. Once, Haley asked if she could make up her own song.

“Can I have a turn?”

“Ummmmm,” Hannah said. “No.”

In a video of that moment, you can hear their dad laughing.

After Hannah’s body was found, Haley talked to TV news crews about her sister.

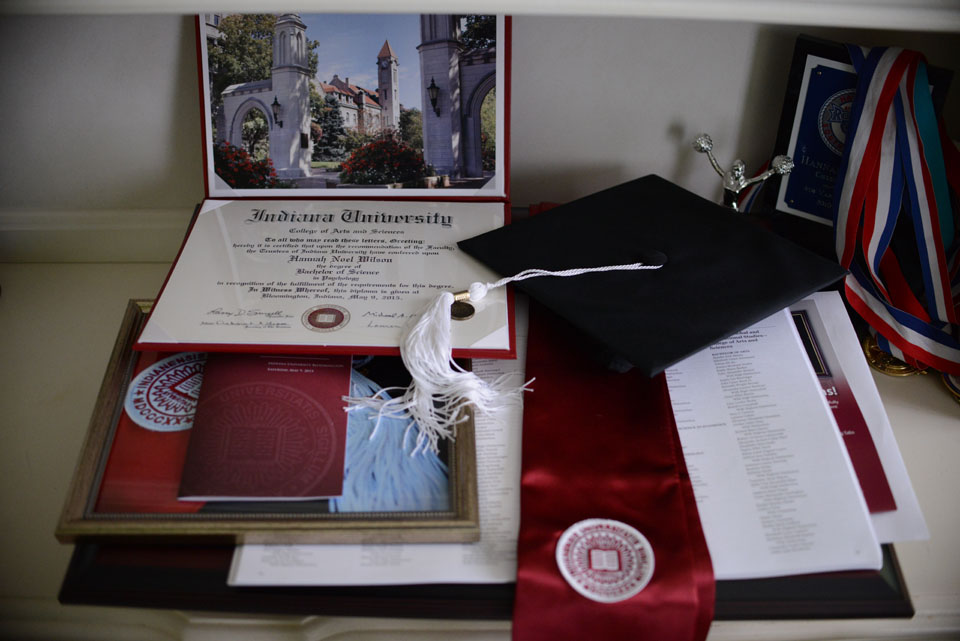

Posing for the iconic graduation photograph in her sister’s place, Haley held Hannah’s diploma and threw her graduation cap skyward in front of the Sample Gates.

There was never any question that Haley would start classes in August. People asked if she was scared to go to IU. She told them in Bloomington she knew she’d feel closer to Hannah. They asked Robin how she could send her daughter to the same campus where her other daughter had disappeared. But Robin didn’t want Hannah’s alleged killer keeping another Wilson girl from living her life.

“He doesn’t get to win again,” she said.

In June, Haley went to orientation. During a question-and-answer session, another incoming freshman asked if IU was safe. “Because of the murdered girl.”

Haley spoke up: “That’s my sister.”

The room fell into an awkward silence.

“And I don’t feel unsafe here,” Haley continued. “You shouldn’t either.”

All around her, she saw signs. She would be thinking about Hannah and a song Hannah loved would play on the radio. When she would talk about Hannah with her roommate, pictures and paintings fell off the walls of her dorm room.

On campus, Haley repeatedly heard students making jokes about “the dead girl.” They warned each other, “Don’t let someone get you.”

The callousness upset Haley. Still, she said she believed the jokes were a defense mechanism, and she felt bad others were frightened when she was not. The jokes made her wonder how she wanted to be treated. Did she want people to tiptoe?

She found solace in the messages Hannah left behind in her paintings. She often thought of the one Hannah had made for their grandfather, as he was helping their grandmother cope with Alzheimer’s. Hannah painted a Bob Marley quote:

“You never know how strong you are until being strong is the only choice you have…”

Chapter III

Two summers ago, Robin Wilson had a dream that Hannah was going to die before graduating. She pictured herself delivering the eulogy, as Hannah’s friends looked up at her from the front row.

Robin woke up and ran to her daughter’s room to make sure she was OK. When her mom shared the dream, Hannah laughed.

“I don’t want a stuffy funeral home,” Hannah said. “I want gerber daisies on my casket. And I want you to throw a party.”

On the Sunday after the murder, the Wilson family and Hannah’s Gamma Phi Beta sisters organized a concert at Dunnkirk nightclub. They ordered Peach Ciroc bottle service and danced.

At the funeral, her casket was draped in colorful gerber daisies.

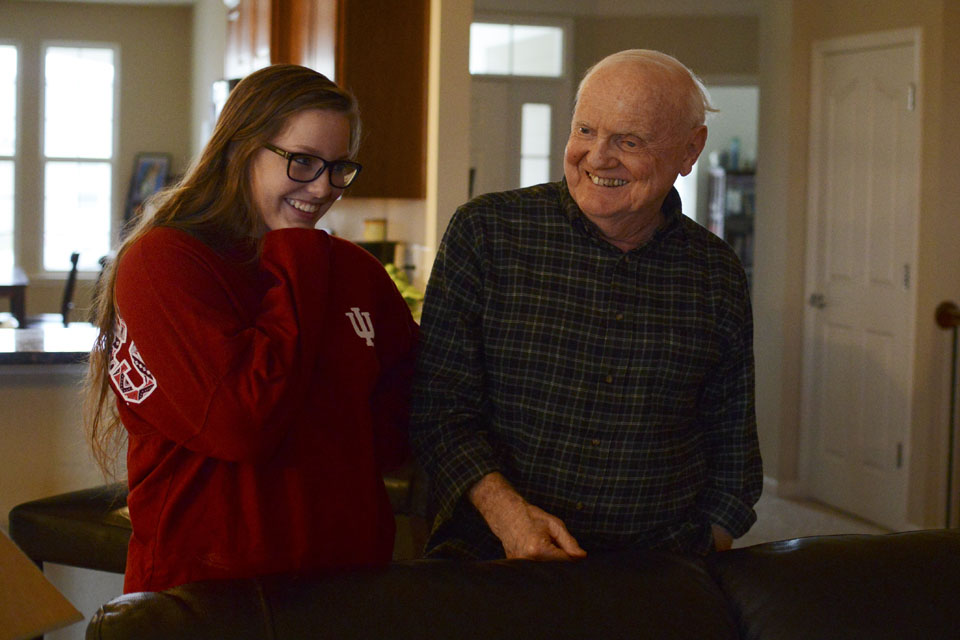

During Haley’s first semester at IU, Robin remembered how close the girls were despite their age difference. When Hannah came home from college, she would call out, “Hi, Mom,” and sprint upstairs to Haley’s room. For hours, Robin could hear them laughing.

“They had their own sister language that I didn’t know,” Robin said in November.

Robin is proud of Haley for attending IU, but she sees Haley’s determined stoicism as a way to avoid facing the horror of what happened. Robin worries that the raw pain will catch up with her younger daughter. When Robin grieves in front of Haley, her daughter tells her Hannah wouldn’t want them to be sad. Robin doesn’t agree.

“Of course Hannah wants us to be happy,” the mother says. “But Hannah wants to know that we miss her terribly.”

When Robin feels like crying, she cries. She often visits the grassy clearing in Brown County where Hannah’s body was found. That’s the place where she feels the most connected to Hannah’s spirit.

One day, Robin asked Haley to join her in a visit to the clearing. Haley agreed on the condition that her mother would not talk about how Hannah died. She didn’t want to know the gruesome details.

They drove east from Bloomington to Plum Creek Road, a 20-some minute drive that made Haley sick as she thought about her sister’s last moments.

Her mother turned off the road and stopped at a small patch of wildflowers. Neighbors of the site had placed a white cross and a Tibetan prayer flag.

Haley took it all in. Then she was ready to leave.

“If I could choose, I would never go back there again,” Haley said. “I didn’t find it peaceful.”

Chapter IV

That fall, a coach offered Haley a spot on the IU All Girls Cheerleading team.

She hesitated, even though she had cheered competitively since elementary school. But Robin reminded Haley that cheering could help shape her own identity. Haley needed a sports physical first. She went to IU Health and filled out the forms, which asked about family deaths.

Older sister, Haley wrote, age 22, murder.

She gave the forms to the woman at the front desk, who looked them over and asked how her sister had died.

Haley looked at her blankly. Hadn’t she read the forms?

“She was murdered,” Haley said.

“Stupid me,” the woman said.

Yes, stupid you.

“Well, it’s been four months,” the woman said, attempting to gloss over her mistake. “Aren’t you over it by now?”

Haley liked to cheer because it got her out of her room and kept her busy. At practice, people don’t associate her with Hannah. IU Coach Julie Horine knew Haley from high school competitive cheerleading and said she didn’t invite her onto the team out of charity.

“We like Haley to be Haley,” she said.

During the Ohio State football game in October, Haley was distracted. Two student deaths at IU had rattled campus and broken her stoicism. Yaolin Wang had been murdered earlier in the week. The night before the game, the body of missing student Joseph Smedley had been recovered in Griffy Lake. His death was later ruled a suicide. The news upset Haley so much that she cried for hours.

The next day, as she cheered on the field, she could not stop thinking about the families of the two dead students. She had come so far in six months, and they were back to square one.

A few nights later, Haley was riding the bus when she passed a vigil in Dunn Meadow for Wang and Smedley. Haley had not planned on attending since she was studying for midterms. But she remembered all those who once supported her. She got off the bus.

Standing in the field among students holding candles, she felt a crippling guilt. Hannah’s vigil had overflowed Alumni Hall. This crowd was noticeably smaller. Like many others, she wondered if it was because Wang was a Chinese student and Smedley was black. Haley didn’t want to think that people had connected with Hannah because she was a white girl from Fishers.

These thoughts haunted her. But the vigil has also opened her up. For so long, she had avoided thinking about death. Haley sent Smedley’s sister a message on Facebook. She told the sister that many people had probably reached out and offered their support, but as someone who actually knew what she was going through, Haley was there for her. And after six months, Haley was OK, and she would be OK, too.

Chapter V

Like his younger daughter, Jeff Wilson prefers to focus on happier memories of Hannah. He and Haley like to watch the videos Hannah made and directed when the girls were young. They laugh over how Hannah would become furious when Haley forgot her lines.

He wonders if it’s good for Haley to mirror his approach, since she’s a more emotional person than he is. He wants to make sure she feels comfortable to seek therapy if she needs it.

“I don’t really cry,” Jeff said. “Haley doesn’t like to, but when she does, she really lets go and it comes out uncontrollably.”

The morning after IU’s Homecoming, he was playing drums in a musical duo named for Hannah on the back patio of the Gamma Phi house. Haley was there too, but she was nervous. It had been a while since Haley last cried, and she knew many of her sister’s close friends would be stopping by. She was worried they would get emotional, and then she would, too. She was determined not to lose control.

A few hours went by and her sister’s friends showed up, and through it all, Haley kept her smile. Then the guitarist strummed the opening to “See You Again” by Wiz Khalifa. In Hannah’s final days alive, she had listened to it over and over. She knew all the words. Hannah was always touched by music with lyrics about losing someone, Jeff said. Now everyone on the patio sang along.

It’s been a long day without you, my friend

And I’ll tell you all about it when I see you again

The other young women, most of them crying, formed a line and wrapped their arms around one another’s shoulders. Jeff left his post at the drums and joined them. Haley held back, sitting by herself and mumbling the lyrics. She had made it to this day, all the way to October, six months after the murder.

We’ve come a long way from where we began

Oh, I’ll tell you all about it when I see you again.

Haley felt compelled to stand. She left the table and joined arms with the group. She bit her lip and looked at the ground, and began to sing.

How can we not talk about family when family’s all that we got?

Everything I went through, you were standing there by my side,

And now you gon' be with me for the last ride.

Leaning against her friends and Hannah’s, she finally broke down.

“I wasn’t even crying because of Hannah,” Haley said later. “I forgot how terrible it is not having anyone older to look up to.”

Chapter VI

The rest of the semester went by quickly. Haley went to class and kept up her GPA. She started cheering at basketball games. She and her roommate binge-watched Grey’s Anatomy and America’s Next Top Model.

In the weeks before Thanksgiving, Haley worried about the holidays. She and Hannah had always gotten through them together, going from Dad’s house to Mom’s, fielding questions about what they wanted to do with their lives. Now Haley was on her own.

Before dinner at her mom’s house, they all held hands. Tears flowed. Someone said, “And cheers to Hannah, too.”

A second later, a camera flew off the kitchen table and hit a wall. The paint is still chipped.

OK, Haley told herself, There she is.

* * *

Most freshmen, at the end of their first semester, look back and wonder how they could have changed so much so quickly.

When Haley finished her finals in December, she knew she had changed. She didn’t know how much had come from grieving and how much was just growing up. In her first months at IU, she had felt herself becoming more compassionate, more open. She had found a voice. She had stopped hiding.

She hadn’t sought counseling yet, but knew that day lay ahead. She still talked about Hannah in the present tense, but was allowing herself to contemplate a future without her sister.

“Graduation,” she said one day in her dorm room. “That’s what’s going to be hard.”

That’s when Haley will have no choice but to confront what’s happened, when she’s walking across the stage to pick up her diploma. She will wear Hannah’s red graduation sash and flip the tassel over Hannah’s graduation cap. They sit on Hannah’s desk at home, waiting.

After she graduates, Haley will start her career. Maybe she’ll work with autistic children. To do that work, she’ll probably have to go to grad school. Then she’ll find the right guy, and Hannah won’t be at the wedding.

When Haley has children, she will tell them about the older sister who taught her everything. She’ll show them the pictures now hanging in her dorm room, pictures of two sisters on the cusp of adulthood. But by then, Haley will look different. Their aunt won’t.

“In 20 years, I’m not going to look how I look right now,” Haley said. “And she — that’s the only face I’ll remember. One day all the pictures will be...old.”

During winter break, Haley turned 19.

“I don’t like that,” she said. “I wish I could just stay this age and stay in this memory. One day I’ll be 22, and she’ll still be 22.”

Hannah will be that age forever, always the senior on the verge of starting her life. Haley said she hates that. She hates thinking about all the things she’ll do that Hannah will never experience. She hates that she’ll go through them without Hannah. She’ll have to teach herself what to do, who to be, how to say goodbye.

No matter what, Haley said she believes Hannah will find a way to be at her side. She will always be the little sister.

About this story

This project is based on five months of reporting. Hannah Alani, Haley Ward and Kelsey Roadruck followed Haley Wilson through her first semester at IU. They attended her classes, rode her bus, hung out in her dorm room and watched her cheer. The reporters witnessed many of the scenes in the story and based the rest on interviews with Haley, her family and friends, as well as court documents.