Thursday, Sept. 21 — This is the last in a four-part series about IU's system of sexual assault investigations. For more information about this series, click here. If you believe you have experienced sexual assault or have an ongoing case and need support, click here for a list of resources. Contact our investigations team if you have further questions or would like to share your story.

***

Sexual violence haunts college campuses across the country. At IU, the damage is inescapable.

In the past couple of weeks, at least three campus rapes have been reported in places where IU students should feel safe. One was reported in Wright Quad, another in Read Center. At Briscoe Quad, a freshman told police she was raped by someone she had met at a party. Another young woman reported a fourth incident, this one off campus, saying a stranger had grabbed her from behind and climbed on top of her on North Walnut Street.

IU is fighting back. The flyers, the banners, the attempts to educate students on consent — all of it matters. But a yearlong investigation by the Indiana Daily Student makes it clear that the University’s attempt to investigate sexual assaults is deeply flawed.

The good news is that IU has the power to fix some of the problems right now.

Here is a list of the critiques cited most frequently and some possible solutions, including approaches already adopted at other Big Ten universities. Most of these proposals would cost almost no extra money and would not conflict with federal guidelines.

IU officials say they are constantly seeking to improve the system. They say they are particularly interested in hearing from students on how to do this.

This is a chance to prove it.

Not enough straight talk from the University. When asked about shortcomings in the system, administrators tend to retreat behind bureaucratic explanations of what policy allows. Some at IU argue that the University's system of investigating sexual assault is “educational,” not “punitive,” and that it teaches problem-solving and decision-making. Students who have suffered sexual assault — and students who have been accused of sexual assault — find this a condescending dodge that glosses over the real consequences of these cases.

Lead the conversation. Create forums for the campus community to share frustrations and suggestions. Find new ways to gather input from those who may not be comfortable speaking in public. Recognize that this is more than a learning experience for students. It is deeply personal. Stop hiding behind policy, and ask if it is time for those policies to change.

Not enough protection for students who report rape. No-contact and no-trespass orders issued by the University are loosely enforced at best, leaving those who have been assaulted vulnerable to harassment and retaliation. IU does not routinely share these orders with its own police department, leaving officers in the dark when students report that their attackers have shown up at their dorm. When students complain, the Office of Student Conduct often goes no further than issuing another warning that simply repeats what is already in the no-contact order. To make matters worse, these orders are only enforceable on campus and not elsewhere in the city.

Share information. When women run into their alleged attackers on campus, it can be hard to prove the contact was intentional. But several women told the IDS they had suffered clear violations, and the University did next to nothing. A few simple changes in the system would help. Create a database that shares all no-contact and no-trespass orders with the IU Police Department. Update the intake protocol at the Office of Student Conduct so that every time a student reports a sexual assault, someone from the Maurer School of Law’s Protective Order Project is on hand to help the student obtain a legal protective order.

IU punishes students who do not cooperate with the system. Investigators in the Office of Student Conduct place holds on the student accounts of potential witnesses and those accused in sexual assault cases. These holds prevent students — even those eager to help in the process — from registering for classes, requesting transcripts and even graduating. The University does not place these holds on the accounts of those who report sexual assault. Even so, the holds are another burden for these women, leaving them feeling guilty for dragging others into such complications.

Stop using the holds. Other universities such as Ball State University, do not use this method of compulsion because they worry that holds will alienate students who might otherwise comply with investigators’ requests. IU should drop the practice, too, especially if its officials are sincere when they insist that their system is not intended to be punitive.

The University keeps evidence secret. Students are usually not allowed to review their own case files until shortly before their hearings. Women who have reported sexual assault are left with no idea of what the accused and others are claiming. Men facing expulsion have no idea how to prepare for their hearings. Either side can ask a lawyer to review their cases, but by the time the files are opened, it can be too late for a lawyer to truly help. IU officials insist that the restrictions they impose allow investigators to work more efficiently.

Open the files to those with the most at stake. When fairness is so essential to both sides, both the accused and their accusers need to know the facts from day one. These students’ desire to keep up on their cases should not be considered an inconvenience. The credibility of any system — at a university or elsewhere — is built on transparency.

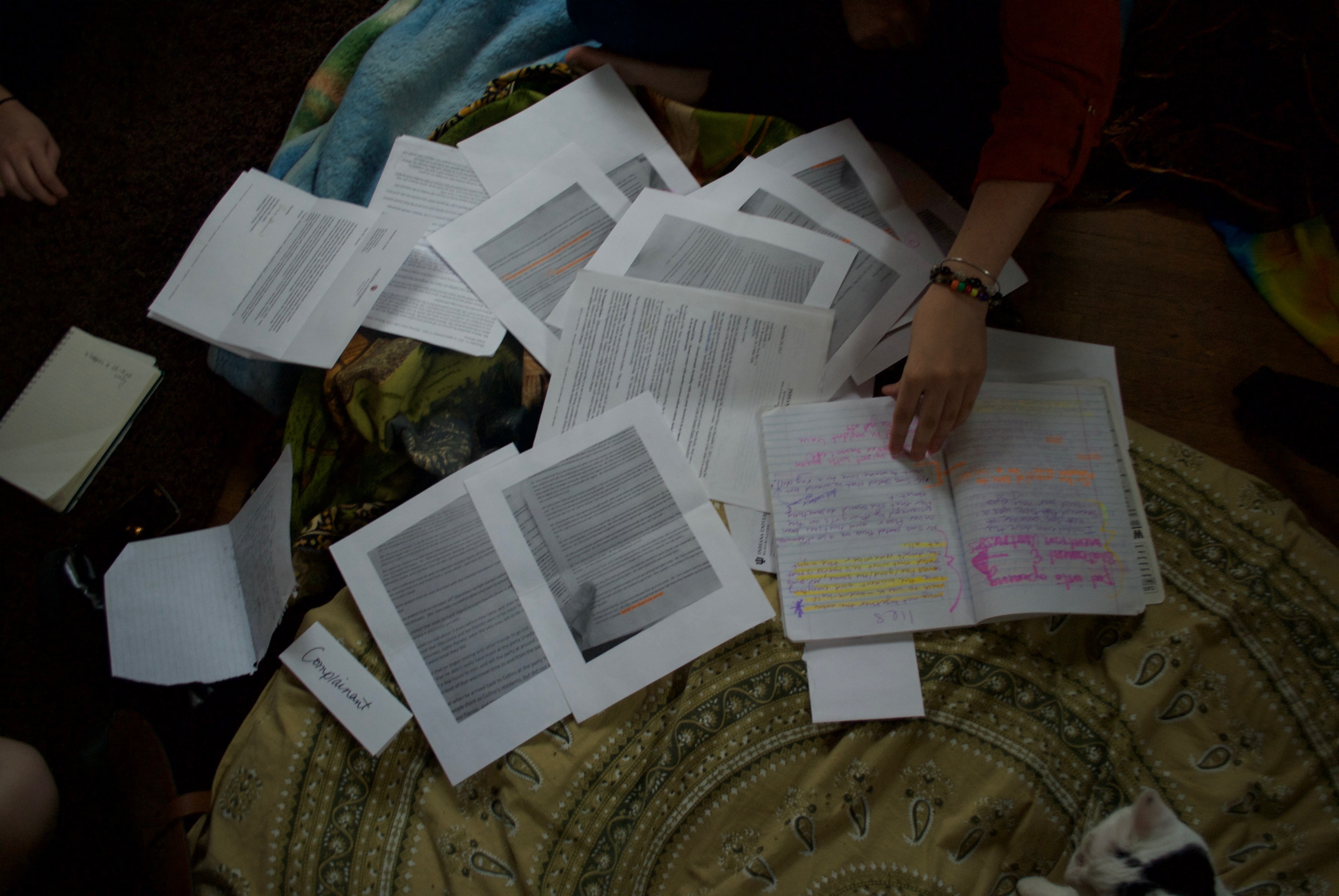

The University will not let students copy their own files. IU does not provide copies of investigative files to the involved parties unless compelled by a legal order, and it does not allow students or their lawyers to make copies of their own. They are allowed to take handwritten notes, but that is it — a challenge when some files run nearly 100 pages long.

IU points out that the files often contain information on several students, and that those students’ privacy is protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. Given that these are sexual assault cases, the officials worry that releasing files could allow medical records and other sensitive information to be posted online or shared among students who are not involved. They note that FERPA only requires universities to allow students to inspect their files, not copy them.

Do more than the minimum. The University does a disservice to students by insisting that it only has to meet the law’s minimum requirements. Is that really the position IU wants to take in such important cases? Other schools have no problem going above and beyond the FERPA minimum. The University of Minnesota provides redacted copies of these files. The University of Maryland releases the entire file to either the accused or their accusers, providing they sign a waiver. There is no reason IU cannot adopt a similar approach.

IU routinely destroys potentially crucial evidence. Attorneys who represent students accused of rape complain that the University discards video surveillance from the dorms and other campus buildings. IU only holds onto the videos for a month, but many cases stretch much longer. Until the students and their lawyers are allowed to review the files, they do not necessarily know what evidence will matter. Are the women looking for video that confirms that the man they have named did enter their dorm on the night in question? Are the men seeking video that shows they did not enter that dorm that night? Are lawyers looking for video that proves their client was elsewhere on campus when the assault occurred? By the time the different stakeholders are given access to the files and better understand the case, it can be too late.

Establish a protocol for preserving evidence. Emily Springston, IU’s Title IX coordinator, points out that not every video contains valuable evidence. Yet there is no way to know unless both sides have a chance to check. One of the first steps IU takes when opening a sexual assault investigation should be immediately requesting and setting aside any video potentially relevant to the case — including video from another location that might confirm the alibi of the accused.

The University puts students in the uncomfortable position of defending their own cases. These students — many who have never had to represent themselves in a formal hearing of any kind — complain that IU makes them play lawyer. University policy forces the actual lawyers in these situations into silence.

Explore other options. Some universities, including the University of Minnesota, the University of Iowa and the University of Wisconsin, allow attorneys to participate in hearings and represent their clients. At Iowa, the university will connect students with resources if they can't afford their own lawyer. Consider speaking with officials at these and other schools to see how different models work.

Those entrusted to decide these cases are underqualified. The three-member panels that hear sexual misconduct cases are made of IU employees. Few have legal experience, but the University believes its annual day-and-a-half-long training is qualification enough to hear evidence and place sanctions. With tricky evidence standards and the complications of defining what it means to give and receive consent, students and attorneys argue this training is not enough.

Get someone who is qualified. Consider inviting members of the legal community who are specially trained in the complexities of sexual assault cases to serve on hearing panels. George Mason University has done this using a three-member panel of retired judges. Simpler still: Recruit experienced professors from the Maurer School of Law or from IU’s Department of Criminal Justice to help decide cases.

IU controls every step of the process. The Office of Student Conduct investigates reports of sexual assault. University employees decide the cases and hand out punishments for students they believe have committed rape. And the dean of students reviews appeals. Attorneys argue it is unfair for every stage of these cases to be decided by employees whose paychecks are signed by IU.

Allow independent review. If the University’s system is as strong as it claims to be, its investigations and hearings should stand the test of external review. When a student appeals IU’s decision, let someone from outside of the University consider the appeal. The University of Michigan does this, allowing an attorney from outside its system to consider whether cases were heard appropriately.

Appeals are rarely granted, even when new evidence surfaces. The University only considers appeals claiming that IU did not follow its own policy — a policy some students and attorneys say is flawed to begin with — or that the University’s punishments are too harsh. Students are only allowed to appeal once within five days of receiving IU’s decision. In a system designed to provide expedient answers, the results of rape kits and DNA testing are rarely completed in time. While University officials say they will consider new evidence after the appeals window closes, one attorney was discouraged from sending forensic results, citing IU's lack of training for those who consider appeals.

Consider new evidence. Amend the sexual misconduct policy to accept appeals on a basis that new, factual information has become available after the University hearing. This protects both students who have reported and been accused of sexual assault. What if the DNA does not match a student suspended or expelled for sexual assault? What if such evidence proves a student did commit rape after IU’s system cleared the student and allowed him or her to return to classes? Further train appeals officers on forensic evidence standards.

It has seldom discussed the causes of five investigations opened by the federal Office of Civil Rights and the results of internal investigations into former employees, including that of former Office of Student Ethics director Jason Casares. After a ballet student reported being sexually assaulted by an IU Jacobs School of Music lecturer, the University waited six weeks to involve campus police in its investigation. Like in the case of Casares, the University conducted an internal investigation and refused to share its findings.

Light and Truth. Answer tough questions about why these federal investigations have been open for years and explain how IU plans to correct its mistakes. Speak openly about investigations of former employees, and be transparent about why they are no longer here. Invite those who have the most at stake — students, attorneys and other community leaders — to take an active role in fixing the system, and live up to IU’s motto of Lux et Veritas.

| School | Enrollment | Model type | Appeal | Investigative file | Adviser |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baylor | 16,959 | One or more investigators, which can be university employees or external consultants, submits findings to three-member panel of Baylor employees for in-person hearing. | Either student can submit a written appeal to the vice president of student life within three days of the hearing on grounds of procedural error or inappropriate sanctioning. | When investigation finishes, students can review preliminary investigative report and take five days to meet again with investigator or submit additional information. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| George Mason University | 34,000 | One or two investigators, which can be university employees or external consultants, create an investigative file and recommendation for three-member hearing panel of retired judges. | Either student can submit an appeal within five days of decision to a University appeals officer on grounds of new information, procedural irregularity, hearing officer bias or the severity of sanctioning. | Students are given five days to review a draft investigation report, meet with investigators and submit new evidence. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| Indiana University | 43,213 | Two investigators who are IU employees prepare investigation report for use in in-person hearing, led by three-member hearing panel of IU employees. | Either student can appeal within five days to the dean of students on basis of procedural error or inappropriate sanction. | After the investigation ends, students are given 10 days to review an investigation report and preliminary investigation report, and provide clarifying information to investigators. Only handwritten notes are allowed during in-office review. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. This person can be a university-provided student advocate or confidential victim advocate. |

| Michigan State University | 50,344 | A university investigator collects evidence and makes a finding to refer to three-member sanctioning panel made up of one student, one faculty and one staff member that convenes weekly. Students don't appear before panel. | Either student can file an appeal within 10 days for review by university administrator on grounds that finding had no basis in fact, there was a procedural error, or sanctioning was inappropriate. | After investigation concludes, either party can review preliminary investigation report and provide feedback before finalized and given to sanctioning panel. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| Northwestern University | 16,415 | A single investigator, either a Northwestern employee or trained external professional, collects evidence for three member hearing panel comprised of faculty and staff. The reporting student and accused student appear individually before panel. | Either student can appeal five days after learning outcome of case to a university administrator on grounds of new information, procedural error or inappropriate sanctioning. | Both students are provided the investigation report five days before panel. They can review the report and submit questions to be asked by the hearing panel within 72 hours of receiving the report. After hearing, records can only be reviewed in office with no copies allowed. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| Ohio State University | 59,482 | A university employee investigates and can bring charges to be heard by a board of between four and eight university faculty and staff. Both students are encouraged to attend hearing. | Either student can appeal to a university administrator within five days of being notified of a hearing result on basis of a procedural error, new evidence is available or the sanction is thought to be disproportionate. | A single record is kept of the hearing by the university and may be reviewed by either student if an appeal is filed. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| Pennsylvania State University | 47,261 | A university investigator compiles evidence in an investigative report to be given to another university employee, called a case manager, who can recommend charges and sanctions. These are then referred to a Title IX decision panel of staff and faculty. Both students can appeal before panel, but are never together in a room. Students can review others' statements through video of hearing. | Either student can request a sanction review or appeal within five days to a university employee on grounds a student was deprived of their rights, new evidence is presented or sanctioning was not justified. Appeals can be referred to a new hearing board or Title IX panel. | Both students are given a five day review and response period of the investigator's draft packet containing witness statements, evidence, etc. | Students can select any person or attorney, including trained university personnel, to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| Purdue University | 40,451 | A university investigator compiles report and findings for one of three administrators to review with a three-member panel of university faculty and staff. Students may give a brief statement to this panel before it decides if a policy was broken. If so, this is forwarded to another administrator to determine sanctions. | Either student can file a written appeal to the university's vice president for ethics and compliance within 10 days. | Students can review a preliminary investigation report for seven days and respond in writing. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| Rutgers University | 50,146 | One investigator or a team of investigators submit an investigation report to a Title IX coordinator who determines if a policy was violated. The Title IX coordinator passes the report to a student affairs officer who, after contacting the accused student, can refer the case to one hearing officer who collects written statements and decides responsibility and sanctions. | Either student can appeal within five days to a student affairs administrator on a basis that the conclusion reached wasn't supported by facts of the case, there was a procedural error, new information was found or the sanction was disproportionate. | Students are guaranteed one copy of the investigation report and a review of any information to be used in hearing with redactions of names or identifying information. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| Stanford University | 16,336 | One investigator determines if a charge should be brought. The case is then referred to a three-member hearing panel of university faculty, staff and graduate students, which hears from student separately. Although, students may listen to one another's testimony via phone or Skype. The panel then meets a second time with no students present to determine sanctions. | Either student can submit an appeal within 10 days to an appeals officer who consults with the university Title IX coordinator on a basis of a procedural error, new evidence becoming available or a question of whether decisions and sanctions were reasonable. | Students can review file electronically when a decision is made about whether or not to bring a charge. Students can also review redacted evidence logs and request an evidentiary specialist review. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. The University also provides nine hours of legal consultation from a list of approved lawyers at no cost to the students. |

| University of Illinois | 44,880 | There are at least two investigators, with one taking lead and determining charges and recommending a finding of responsibility. A three-member panel comprised of university faculty, staff and students reviews investigation reports and interviews investigators to determine responsibility and sanctions. | Either student can appeal on basis of procedural unfairness, inappropriate sanctions or new information. Appeals are heard by a committee of two faculty members and one student. | Both students can review initial report from investigators and provide written response. Students then have five days to review a revised report. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| University of Iowa | 33,334 | One employee investigates and decides charges before presenting to a single hearing officer, who is selected from outside of the university based on law or previous hearing experience. Students can appear with advisers to bring evidence, provide statements and cross-examine witnesses. Hearing officer makes recommendations for sanctions to university president. | Either student can request a review within 10 days of decision. Reviews are heard by three-to-five member panel. | Any student charged with a student conduct violation is provided the hearing officer's written report. | Students are allowed no more than two representatives or attorneys who play active roles in the hearing. The university may assist a student in finding similar services if they can't find their own legal counsel. |

| University of Maryland | 37,000+ | One or more investigations, who could be university employees or external consultants, are assigned to each case. The report could then be referred a five-member standing review committee of faculty and students where both students appear in person. The committee then decides responsibility and directs the case to the director of student conduct who decides sanctions. | Either student can appeal within five days of decision on grounds of a procedural error, new evidence or a disproportionate sanction. Appeals are heard by a three-member appellate body consisting of at least one student. | Students can review draft investigation report within five days of its completion and suggest any additional information. Students are given a confidential copy of the final report. | Students are allowed one adviser, which can be an attorney, and one support person throughout the process. Both roles are non-participatory. |

| University of Michigan | 44,718 | A university investigator creates investigative report and determines findings for placement of sanctions by a three-member sanctioning board made up one student and two faculty or staff. The board meets weekly and will review investigative reports before placing a sanction. | Either student can provide a written appeal within seven days of sanctioning on grounds of procedural error, new information, or the finding or sanction was inappropriate. The appeal is heard by an external reviewer, typically an attorney from outside the university system. | Both students are sent a preliminary investigation report to which they can suggest additional information be added in a five-day review period. A final report will be provided to both students. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| University of Minnesota | 51,580 | A single university investigator creates a report including allegations, analysis and findings for additional staff review in which further investigation can be recommended. A Student Sexual Misconduct Subcommittee hearing of three to five panelists decides findings and possible sanctions. Students never appear at the same time before hearing panel. | Either student can appeal to an appeals officer within five days of receiving the university's decision. | Students are given a complete investigative file with names of witnesses redacted until the hearing, where a witness list and redaction key is provided. | Students can bring adviser, advocate, attorney or support person to investigative meetings. University offers advisers and lawyers can represent students. If this is the case, a university lawyer can represent the university in the hearing. |

| University of Nebraska | 25,897 | A single university investigator weighs evidence and decides if there's grounds for sanctioning. If suspension or expulsion is considered, a three-member university conduct board decides sanctions based on a hearing with both students present. | Either student can appeal in writing to an appeals officer within seven days of hearing on basis of procedural error or inappropriate sanctioning. | Both students can inspect all evidence and a list of witnesses prior to a hearing. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| University of Notre Dame | 12,292 | A university employee conducts an investigation and consults with two administrators to determine findings and sanctions. | Either student can appeal the recommended sanctions through an administrative review proceeding. Both students may attend in person or request to attend through electronic means. A three-member board of faculty and administrators will determine if a procedural error, new information or sufficient evidence supported the original finding. | Students are given seven days to view a preliminary investigative report and provide a response. Students will then be given five days to respond to any additional information added. A final report can be viewed in-office, with no photos or copies allowed. | Students can select any person or attorney to serve a non-speaking, support role. |

| University of Wisconsin | 43,338 | A university investigator compiles a report for the assistant dean of students to review and decide if policy was violated and what sanctions apply. | If no sanctions are brought, the student who reported assault can request a three-member review panel of students, staff and faculty within seven days of the dean's decision. The panel will review the investigation file and written statements to decide if a sanction should be placed. If the dean decides to bring sanctions, an accused student can request a hearing within 10 days of this decision. A three-member panel, with at least one student member, will oversee a hearing where both students can bring witnesses and question one another to determine if sanctions should stand or be changed. | Students are provided access or copies to investigative findings. | Students can bring any adviser, including an attorney, of choice through the university system. In most cases, advisers are non-participatory, but in some cases, advisers can assist in presenting information and questioning witnesses in hearings. |