Paul Post rolls out of bed and stumbles in the dark to the bathroom, dodging his boots and a bulletproof vest on the floor. It’s 4:20 a.m. It takes him two alarms to get up.

He steps into his pants and boots. He checks the cylinder on his backup gun, a Smith & Wesson 638, and holsters it on his left ankle.

As he gets dressed, Paul sees a Bible quote from 2 Timothy 4:5 hanging above his gun cabinet: “Keep your head in all situations.”

A challenge coin, earned after completing hostage negotiation schooling, goes into Paul’s pants pockets, along with a handkerchief, leather gloves and two pocketknives.

Paul buckles himself into his duty belt and hooks on a flashlight and a portable radio. He checks that his Glock 17 is loaded, holsters it.

As he pulls out of the garage, he passes an American flag billowing from his porch.

On any given work day, he might give out a few tickets. He might be screamed at, spit on, punched or kicked.

A Christian since childhood, Paul has prayed every morning for safety, wisdom and peace since he became a police officer 17 years ago. Lately he’s especially prayed for wisdom in negotiating with the City of Bloomington as the president of the local chapter of the police union.

Advertisement

His coworkers – his friends – are counting on him to secure benefits for them. His wife is counting on him to set a good example for their two kids. The city’s team is counting on him to wrap up the negotiation quickly.

Paul is counting on himself to do a good job. All this struggle has to be worth it.

***

Paul Post speaks as head of the police union representing the bargaining unit at a city council meeting Sept. 18. The union pleaded its case to the council amid a long year and a half of negotiations.

The negotiations started in late July 2018, but Paul and other officers say the last good contract ended a decade ago.

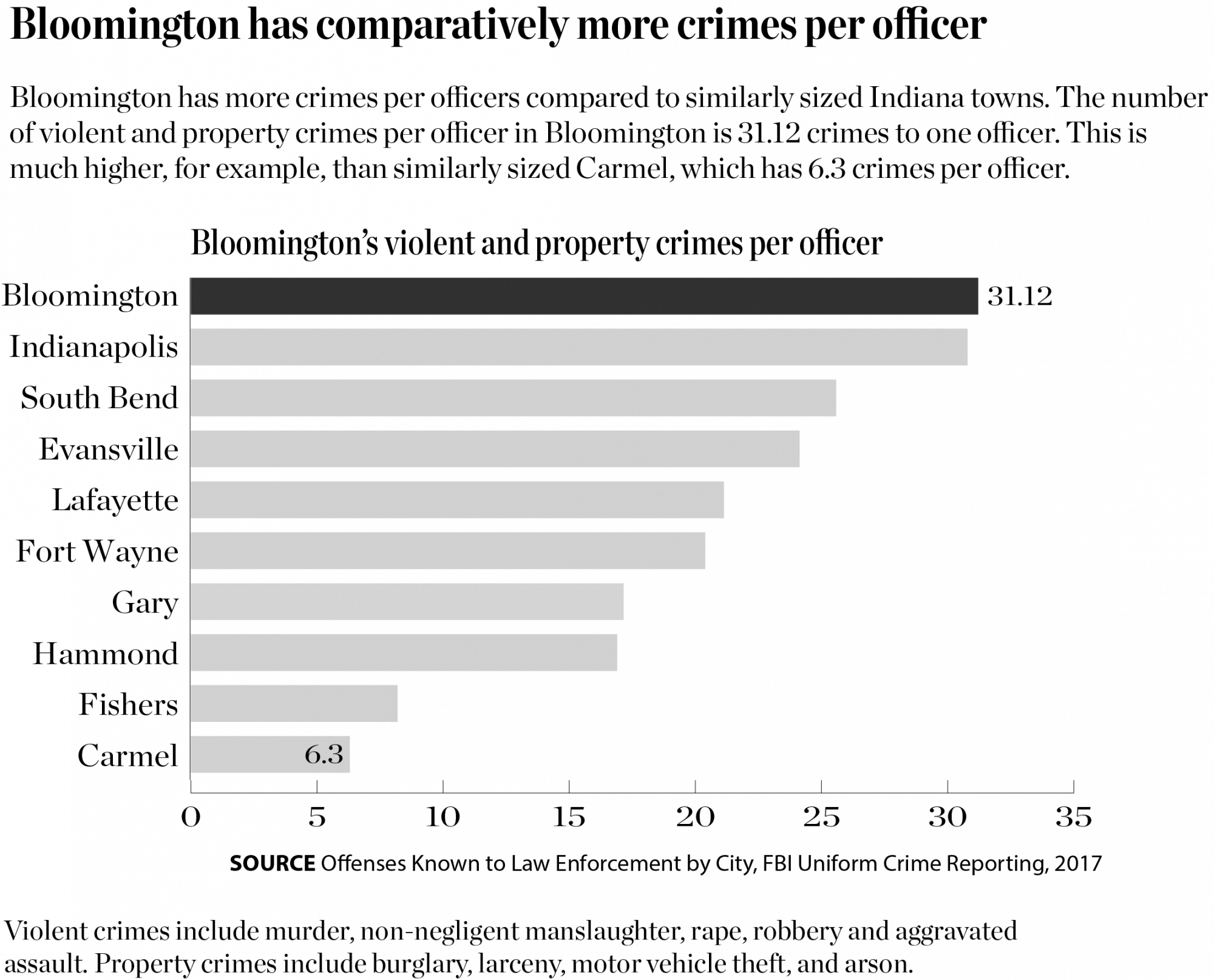

Paul and other members of the police bargaining unit have spoken at multiple city council meetings, offering statistics about being overworked and underpaid. A salary study from 2018 compared Bloomington Police Department to those of 19 other cities in the state.

On average, agencies had 1.7 police officers per 1,000 residents, according to the study. BPD had 1.2 when fully staffed with 103 officers. Detective Jeff Rodgers, the bargaining unit’s numbers guy, said the department hasn’t had a full staff in years. The department is at or below minimum staffing almost year-round. There are six positions open now.

Each shift should have about 15 to 20 patrol officers, Paul said. When a shift is understaffed and no officers choose to work overtime, an officer who worked the previous shift is expected to fill it. It’s mandatory if the shift is down two officers. In November, Rodgers said, officers had to pick up extra shifts at least 62 times.

One officer came to work sick and went to buy cold medicine during his shift. He was still taking it the next day.

One officer had to miss his brother’s wedding. His wife went alone.

One officer couldn’t take time off for his own wedding. He quit.

Paul’s family often celebrates Christmas twice. His wife takes the kids to see out-of-state family on Christmas Day, and they find time to have their own Christmas later. They aim to do it in January before the kids go back to school. But they’ve had Christmases in November, December, even February.

Kristy would tell the kids Santa came early or while they were gone. The kids didn’t question it much. “I tried to make things really special,” she said. “They are pretty gullible.”

Police gain national attention

The Black Lives Matter movement gained speed after the February 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin. According to a database The Washington Post maintains, at least 850 people have been shot and killed by police this year in the U.S. The database has data from 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015.

The City of Bloomington keeps public databases on officer involved shootings dating to 2016. The only record of one of these shootings was Oct. 3, 2017, in which a 31-year-old white man died.

A survey this year revealed about 37% of residents rated resident interaction with BPD as excellent or good.

Police departments across the country are seeing fewer applications, paired with more exits and retirements, according to a 2019 report by the Police Executive Research Forum. Chief Michael Diekhoff said the economy is doing well now, and government entities typically can’t compete with salaries and benefits offered in the private sector. Recent media coverage of law enforcement doesn’t help, he said.

Rodgers said Bloomington is the seventh-largest city in Indiana, but BPD ranks 66th in pay.

With salaries like that, coupled with the national trend, the department can’t recruit new officers nor keep the ones it has, Rodgers said. Since 2016, at least 46 have left — twice the rate of the previous four years. Some retired, but most transferred to other agencies. One of the most recent officers to leave was a new recruit. BPD paid for him to go to the police academy, but he left for a higher-paying job.

Deputy Mayor Mick Renneisen said the bargaining unit’s numbers comparing BPD to other agencies look at base pay, and most officers make more than their base pay. A BPD officer can earn more money for working overtime, having a certain level of education, getting extra training, having a specialty assignment and more. Other agencies have similar opportunities, but pay structures vary. “It’s not an apples-to-apples comparison,” he said.

Paul said other agencies pay more as base pay and bonuses. He and many officers have outside part-time jobs to rake in extra cash. Paul’s side job is to do security checks at a church.

The city wants to give the chief more say in officers’ shifts, which will spread senior officers more evenly, Renneisen said. Diekhoff was a BPD patrol officer 32 years ago, and he said working with senior officers as a new officer was useful for him.

Bargaining unit members want officers to choose their shifts based on seniority. Paul said many officers choose shifts to maximize time with their families.

The conditions, negotiations and day-to-day police work create a stressed home life, Paul said. “The pressure from both sides wears you down.”

***

Paul Post talks to his wife Kristy before she has to leave to take their daughter Alli to cheer practice Nov. 4. Paul had spent the afternoon baking Kristy a birthday cake.

Kristy, Paul’s wife of 18 years, wakes up hours after Paul does. In the shower each morning, she prays.

It goes like this: “God, thank you for Paul. I ask you to protect him today. Give him the courage and strength he needs to make it home safely. Help him make wise decisions, be a leader and help those in need. Give him the knowledge, the best thing to do for each call, the words to say when he needs to speak and his ear when he needs to listen. Help him feel rested even though he is tired and help him feel loved, appreciated and supported even when he may not think that he is. Thank you for Paul and for the man, husband, father and officer he is. Please keep him safe and help him come home each night to Wyatt, Alli and me.”

Sometimes she asks herself: “How can I send him out there every day?”

Kristy and Paul met on the first night of freshman orientation at Anderson University in 1997.

The next day, Kristy’s boyfriend from home called her to break things off. Paul called her afterward, and he could tell she was upset. Paul invited her to the lobby of his dorm building to talk. As Kristy talked, Paul listened. “Don’t worry,” he said. “It’s his loss.”

Advertisement

They started dating that fall. Paul worked security, and he’d take her on late-night dates driving her around in the security golf cart.

Dating Paul made Kristy aware of the dangers around her. He would only hold her right hand with his left, in case he needed to get to his gun.

As she and Paul got more serious, she worried about being a police officer’s wife. “I don’t know if I can do this,” she remembers thinking.

Kristy did what many girls would’ve done. She consulted her mom. Her mom told her, “No one’s guaranteed anything.”

Her mom would know. Kristy’s dad, a preacher, died of cancer when Kristy was 11.

“I can’t live in fear,” Kristy said.

Today, Kristy has embraced her role as an officer’s wife. She painted the dining room bright blue — “police officer blue.”

Paul, Kristy, Alli and Wyatt Post pray before dinner at their home in Bloomington. Their dining room is just one room decorated with law enforcement-themed memorabilia.

Their seventh-grade daughter Alli sits at the dining room table working on decimals, fractions and percentages.

On the wall behind her is a poem. It starts like this: “My daddy is a policeman who works hard night and day. ‘Lord, please bring him home to me,’ I ask every time I pray.”

“As a policeman, he protects and serves, hardly ever given the respect he deserves...”

Paul is off today, so he’s packing her lunch.

Alli’s favorite thing about her dad being a police officer is bragging to people at school.

“I say, ‘You wanna rob a bank? Well, my dad’s a police officer.’”

When Alli finishes her homework, she goes to the backyard to play with the family’s new puppy, a mix of Australian blue heeler and jack russell terrier.

The Posts are still debating what to call him.

Wyatt, a high school freshman, wants to give him a police dog's name – Major, Sarge or Sniper. Alli is fighting for Oliver, Murphy or Meatball.

The dog had come with the name Wilbur.

“I vote Wilbur,” Paul says with a laugh.

***

The police officers need to be reasonable, the city’s negotiation team said. They need to think about equity with other city employees.

Paul said police officers can’t be compared to most other city employees.

Paul’s been screamed at, spit on, punched, kicked. He’s been exposed to another officer’s pepper spray. He’s cleaned up urine and puke. (There’s a reason the back seats of patrol cars are hard plastic.)

He’s performed CPR on a dying baby.

Paul was first to respond to a call that a baby wasn’t breathing. He rushed to a decrepit house that was serving as an at-home daycare. The woman in charge fled because there was a warrant for her arrest in another state. When Paul got there, a man was hysterical and yelling. Paul did CPR on the baby until the fire department arrived. He carried the little body to the ambulance. Paul can tell you exactly where the house is. He drives past it sometimes.

He’s watched a car crash victim take her last breath.

There was a little red car on Country Club Drive. “I can see the car,” Paul said. The driver was impaled on the steering column. The driver was talking, but Paul knew she wouldn’t be talking for much longer. Paul reassured her the ambulance was coming. She died as she was being removed from the steering column. Crushed chest cavity. Internal bleeding.

He’s lowered people who hanged themselves down into body bags.

One was a college student who hanged herself from her bedroom ceiling fan. Her roommates had a party that weekend. They were in the midst of a fight. They assumed she was home and didn’t want to come out of her room. It turned out, they were home with her corpse all weekend, and the only thing separating them from her body was the girl’s bedroom door.

One was a man who had rigged a noose using a tall tree branch. The man had climbed onto the roof of his detached garage and jumped. Paul found him swinging.

Advertisement

One was a man who hanged himself in a tree next to State Road 37, now I-69. The man hung there for two or three days before someone reported it. Paul still can’t believe no one noticed him. He said cutting him down was hard. “He was a big guy.”

Despite all of this, Paul believes he was meant to be a cop.

“That’s cliché, I know,” he said. “Everybody says that about their job. But not everybody could do this job.”

***

The police scanner traffic crackled around 2 a.m. Oct. 13, the early Sunday morning of IU Homecoming weekend.

“I got shots fired,” a man said calmly, as if this wasn’t the 314th call about incidents involving weapons in 2019. “It’s gonna be in the area of South Grant Street, Smith. All advised.”

Then, a string of voices.

“I looked everywhere, I got nothing.”

“Coming in at South Grant. I still got shots fired!”

“I got one female shot. We’re at the corner of Smith and Grant.”

“We got two down.”

Jacob Woods works night shifts, 9:30 p.m. to 6 a.m. He was one of about 20 officers, some off-duty, who responded to the shooting. Thirty shots were fired, and two people were injured.

Woods was at home for his hourlong dinner break when the call came in. It took him about 10 minutes to get to the scene, but he said it felt like forever. By the time he arrived, the shooting was over. But Woods described the scene as chaos.

Hundreds of people poured out of the house, leaving their bottles and plastic cups in the street. Someone who lives nearby woke up to the noise and said she heard a girl scream, “Everyone’s dead! Everyone’s dead!” Ubers and Lyfts were trying to pick people up from the scene. Some drivers canceled their rides or refused to service the area.

“I got more people running to the south up here,” an officer said over the scanner. “Get some units to Second Street.”

“We have a large scene. We need some additional aid. Contact IUPD to start setting up perimeter.”

“We’re getting weighed down. Shooter’s possibly on Second Street, somewhere between Lincoln and Grant.”

An officer said something about a man shot in the buttocks. “Affirmative,” another officer confirmed.

“North! Second Street! Coming through!”

“Stand by, he’s armed. I saw he was armed!”

“I need guys in containment. Give me cover!”

“...had a pistol on his right side… I don’t know if he threw it or not. I don’t have eyes on him…”

It’s easy to run out of manpower during the night shift, Woods said, because night shift officers respond to so many incidents while they’re happening.

If there aren’t enough officers, responding to a call can be unsafe for them, Paul said. It can take up to four officers to safely search a small building, such as the Starbucks on Indiana Avenue. For larger, multi-story buildings, four officers might be fine to start with, but more would be needed to secure the outside and each floor. BPD doesn’t always have these kinds of resources.

“All it takes is one big incident,” Paul said.

***

Leading the union and its bargaining team has come at a cost, Paul said.

In mid-April, tensions peaked in the negotiations. The city declared an impasse and got a mediator involved. Paul spoke at a city council meeting for the first time May 1.

Later in May, Paul was removed from his specialty, crisis negotiation.

Paul said Diekhoff reprimanded him for speaking as a BPD officer at a police union event honoring fallen officers of Monroe County. Paul believes he made it clear he was working the event as a union member. He thinks the chief’s actions violated the city’s nonharassment policy protecting union workers.

The officer and the chief differ over the details, but in the end, Diekhoff told Paul he couldn’t trust him to make good decisions, Paul said. The chief forbade him to speak to the public outside of his patrol duties.

Paul later got a change of pay notice. His specialty bonus was cut.

Paul appealed, citing eight policy violations. Ultimately, the mayor upheld Paul’s removal from the negotiation team but overturned the public speaking ban.

Diekhoff said the situation was a personnel issue and declined to comment on the details of it. Paul’s removal had nothing to do with any of his union work, Diekhoff said.

Paul calls it an obvious retaliation for his union work.

***

In April of 2018, Paul began keeping track of how much time he’s devoted to unpaid work for the police union. He said it’s close to 300 hours.

Kristy said she can see the toll it’s taken on Paul. He doesn’t spend as much time with the kids as he did before, and his patience is just a little thinner.

One night last month, Paul sat at the computer in the living room. He stopped typing every few minutes to yawn or rub his eyes.

No more than three feet away, Alli and Wyatt played with Wilbur.

“Don’t rile him up,” Paul groaned. He didn’t look away from the computer screen.

“We’re not riling!” Wyatt said.

Advertisement

Paul was about to send out an important email to the 67 voting members of the bargaining unit. Attached was the city’s most recent contract proposal. The contract needed 51% approval to pass. Paul worried it would be close.

The options were far from ideal.

If they voted for this contract, they’d make steep compromises on salary and shift selection.

If they voted no, they risked having no contract at all. That, they believed, would leave the city free to strip their benefits.

The city disputed that interpretation, but either way, time was running out, and this felt like the city’s last offer.

***

Paul Post sits, waiting for the salary ordinance to be discussed during a city council meeting Dec. 4. Paul had been working on the agreement with the city as head of the police union for more than a year.

The bargaining unit voted Nov. 14 to pass the city’s proposed contract, but Paul called it an act of self-preservation.

The city council approved it Dec. 4.

The city attorney said it’s a relief that the negotiations are over. He said both sides came to a fair agreement.

Paul sat stoically in the back of the chambers. He sat through another hour of the meeting, watching people debate tax revenue recommendations while his mind churned.

The negotiations may be over, but Paul and other union members still aren’t happy.

Paul’s only happy to be done with it.

He doesn’t know if it will fix the problems in the department, but he knows he and the team did their best.

Paul went home, where his kids were sleeping soundly and his wife was waiting up. He pulled into the garage and passed the American flag billowing from the porch.

Add your voice to the conversation. Write to us at letters@idsnews.com.

TOP PHOTO Paul Post stands in the kitchen of his home Nov. 21. Post has to arrive to the station by 5:30 a.m. for roll call at the Bloomington Police Station.

CORRECTION Previous photo captions misspelled the name of Alli Post. The IDS regrets this error.