Untreated

Untreated

Indiana is hit hard by the opioid epidemic. Medical experts say medicine is the most effective treatment. Why aren’t we using it?

Untreated

Indiana is hit hard by the opioid epidemic. Medical experts say medicine is the most effective treatment. Why aren’t we using it?

Dr. Nishanie Gunawardane — “call me Dr. G” — prescribes drugs to drug addicts.

Gunawardane is a psychiatrist who specializes in addiction. She was hired last August at Bloomington’s branch of Centerstone, a series of community-based healthcare providers treating mental illness and substance abuse.

There, Gunawardane works with recovering addicts who are overcome by opioids like heroin and oxycodone and prescribes them other drugs to help them through their addictions.

“It always puzzles me when people say you are replacing one drug with another,” Gunawardane said. “They are not replacing an addiction. They are taking a medication for an illness.”

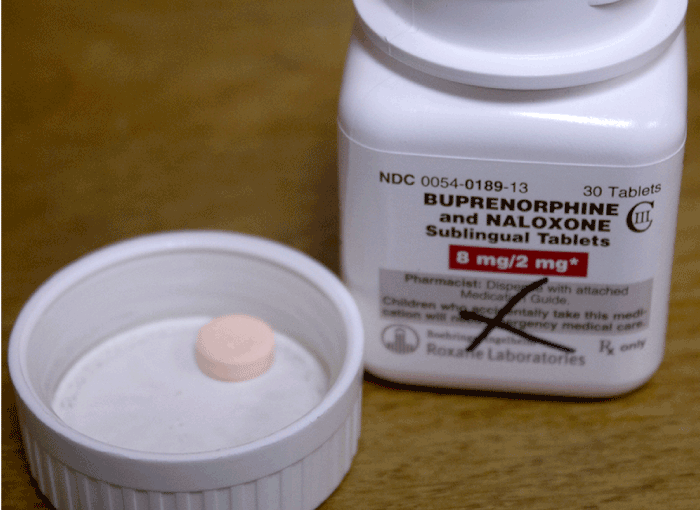

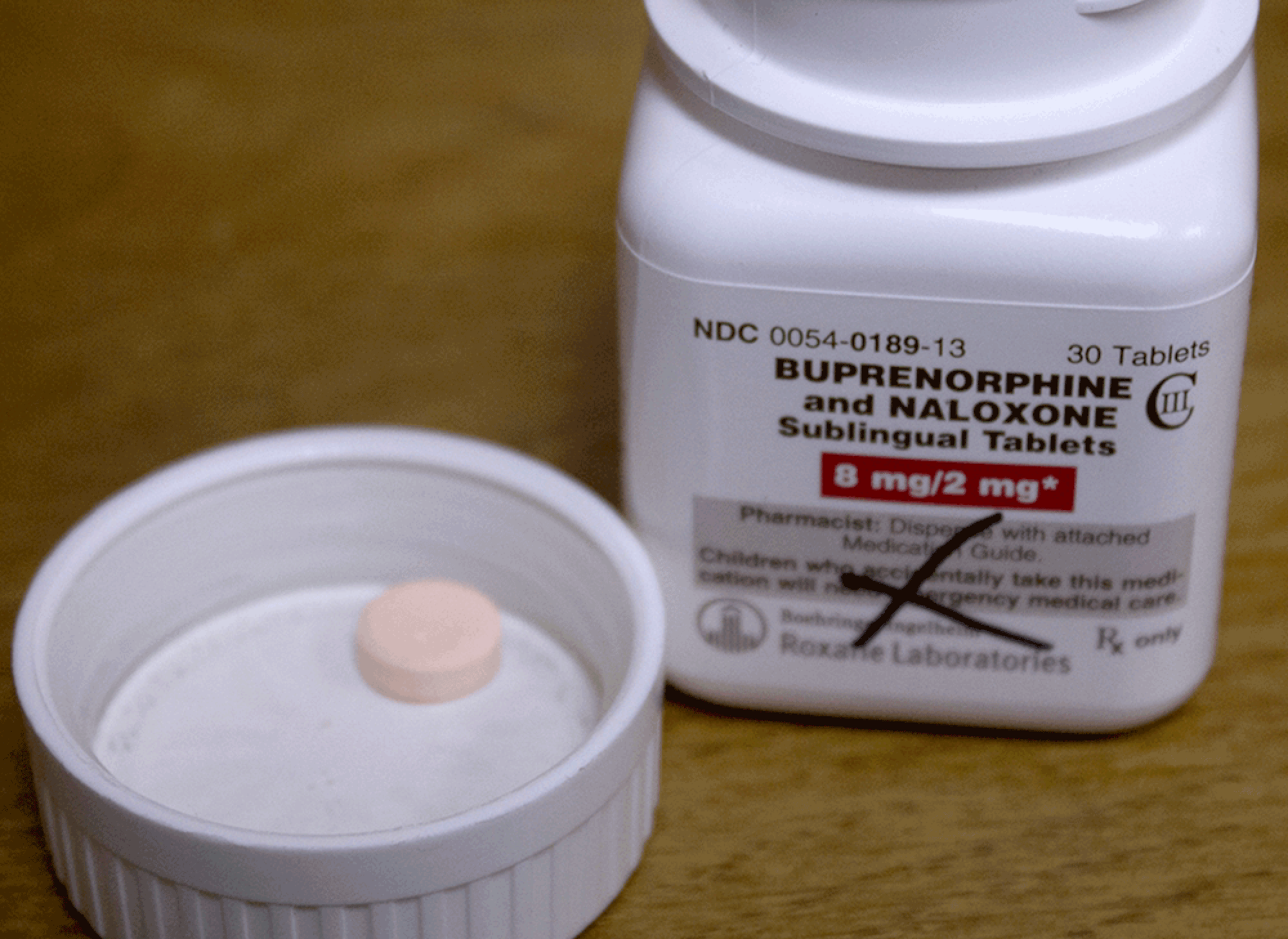

It’s called medication-assisted treatment, or MAT. Recovering addicts take drugs such as Suboxone, methadone and Vivitrol as a long-term means to treat their addiction.

Tom, one of Gunawardane’s patients, came to Centerstone begging to be put on Suboxone. Because of his illegal drug use, the Indiana Daily Student will not include Tom’s last name.

“This drug, it helps me focus on being a normal human being,” Tom, 51, said. “It feels weird to get up in the morning now and be able to shave and shower.”

Before, he would pop pain pills or snort heroin just to get out of bed.

About 2 million Americans were addicted to opioids in 2014, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association.

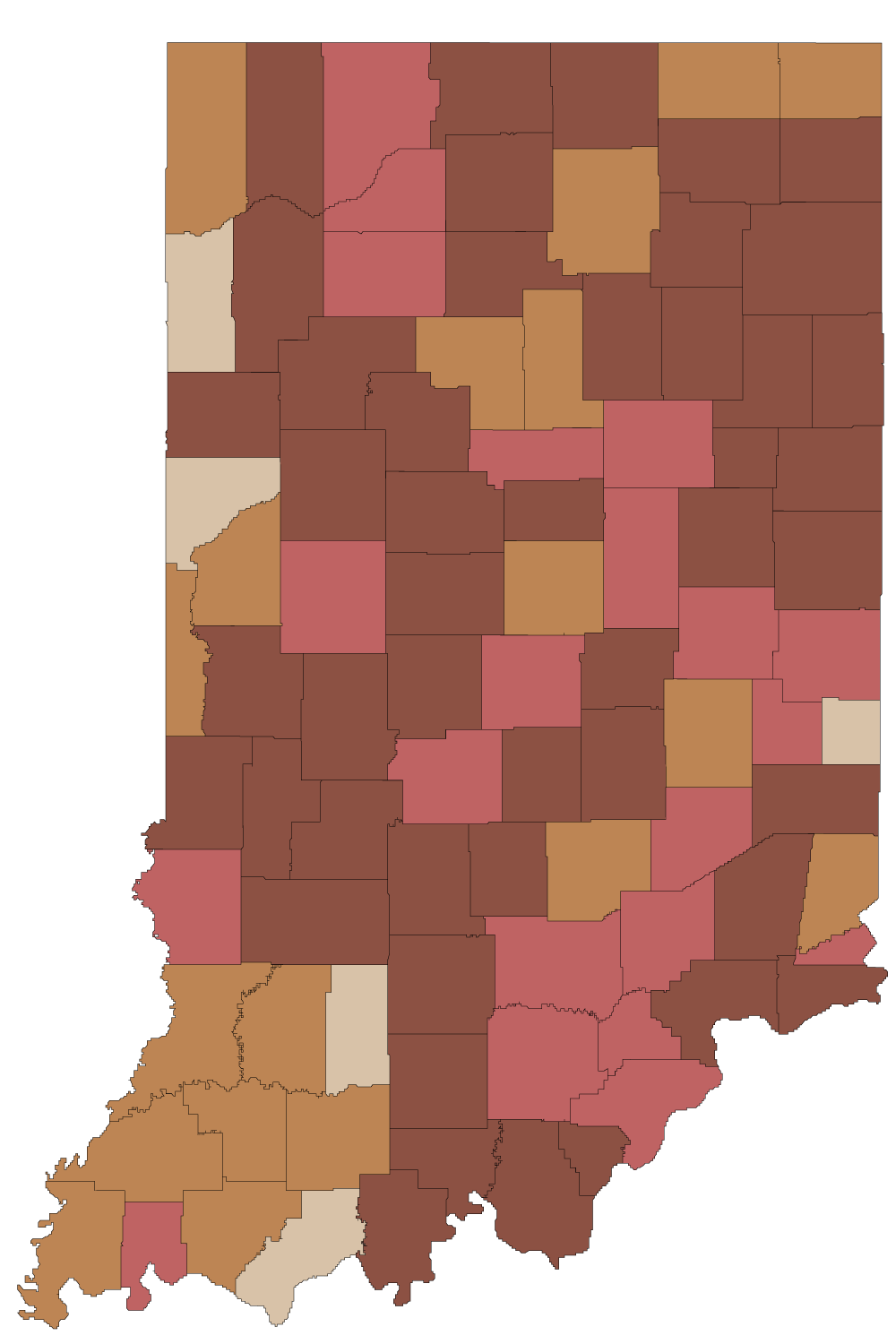

In Indiana, opioid-related deaths have soared — quadrupling in the last decade. According to the State Department of Health, 105 people died in 2004 and 420 died in 2014.

Methadone and the newer Suboxone are opioids. They work by using the same nerve cell opioid receptors that heroin or pain pills activate but don’t cause as strong an effect. Vivitrol works differently — instead of activating the receptor, it occupies and prevents any opioid effect. All three medications help prevent cravings, withdrawal and relapse.

They aren’t miracle medications that will work for everyone, Gunawardane is quick to say. They come with pros and cons.

MAT drugs are widely recommended by doctors and researchers as part of the standard of care for opioid addicts.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine and the American Medical Association have supported this combination of medicine and counseling for over a decade.

But around 90 percent of drug treatment facilities do not use MAT, and call their treatments “abstinence only.”

“Most people who are detoxing or enter into treatment without medicines tend to drop out and relapse and not improve,” said Dr. Marc Fishman, an addiction psychiatrist from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

He‘s just as frustrated as Gunawardane that MAT, which he calls a valuable tool, is underused when addicts are dying from their addictions.

“That tool raises objections in some traditional mindsets,” he said. “We should be using every tool in the tool chest.”

Prescription pain pills took the American pharmaceutical world by storm in the 1990s.

Encouraged by drug companies claiming painkillers such as Vicodin and OxyContin were non-addictive and told they were undertreating pain, doctors wrote prescription after prescription.

“How much does it hurt on a scale of 1 to 10?” they began to ask.

Doctors could dispense the painkillers with little oversight, easily giving out high doses of the addictive pills.

Bloomington is loaded with drugs, Tom said. He remembers first smoking pot as a 12-year-old. He added alcohol and cigarettes in high school and then moved on to pain pills.

“The drugs got stronger, and you need more of them,” he said.

He would spend $200 a day to get his pain pill fix.

“I remember getting a few people in a car and going all over Indiana,” Tom said. “Martinsville, places up in Indy, Bedford. We’d go doctor shopping.”

In 2012, physicians wrote 259 million opioid prescriptions, enough to give every American adult their own bottle of pills, according to ASAM.

A government crackdown on pill mills pushed more users to heroin, said Caleb Branam, supervisor of Centerstone’s Adult Recovery Program.

“So prescription opiates become less available, prices on the street go up, so what’s the next logical thing that’s cheap?” he said. “It’s heroin.”

Four in five new heroin users started out misusing prescription painkillers according to ASAM.

“For a long time, heroin was just like ‘Who uses heroin?’“ Branam said. “Whereas now it’s like ‘I know someone who is addicted or died of an overdose.’“

Heroin overdoses increased nationwide an average of 37 percent a year from 2010 to 2013.

In February, President Barack Obama called for Congress to approve more than $1 billion in funds to fight opioid abuse. The Obama administration wants $460 million to fund medication-assisted treatment, like Gunawardane prescribes.

Before he found treatment, he put his family through hell, Tom said.

“I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy.”

Drug treatment facilities tend to offer one option: abstinence.

This means they do not allow any medicines that contain an opiate ingredient.

“You would go and they sweat it out of you for a few days, and it never took with me,” Tom said. “You’d stay for 30, 40, 60 days. I’ve been through it six or seven times. I always went back to the opiates.”

Medication has traditionally not been part of the formula at these types of recovery centers. They aren’t required to have anyone with a medical background on staff and don’t have a huge reason to be reading studies on advances in medicine, said Basia Andraka-Christou, a law Ph.D. student writing her thesis on MAT.

Mark DeLong is executive director of Amethyst House, a United Way agency in Bloomington that provides inpatient and outpatient services for drug, alcohol and gambling addictions.

“We’re an abstinence-based program,” DeLong said. “While you are in the program, we are going to challenge you to be clean and sober.”

If someone wants to enter the program while taking Suboxone or methadone?

“We would not accept them.”

People get high on those drugs, he said.

“I know a lot of psychiatrists I’ve worked with in pharmaceuticals really want to say ‘Hey, it’s a good thing,’” said DeLong, who has been working in the field of substance abuse counseling for 25 years. “And I’m like, ‘Ok, it’s not the model we treat.’”

Amethyst House uses the 12-step program, Narcotics Anonymous (NA), which is analogous to the Alcohol Anonymous (AA) program. NA includes regular group meetings and emphasizes peer support.

The ability of a 12-step program alone to keep patients sober is difficult to gauge. Dr. Herbert Kleber, director of the Division on Substance Abuse at Columbia University and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, said the program may be as low as 10 percent effective.

“Of the 100 people who start AA January 1, by December 31 only about 9 or 10 are attending,” Kleber said.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse has said even fewer studies exist on the effectiveness of NA than AA.

MAT can complement 12-step programs, Gunawardane said. The standard of care emphasizes medicine should be accompanied by counseling and behavioral therapy.

“I would like patients who are new to recovery, who are still struggling, to be going to some sort of addiction groups,” Gunawardane said, and named NA, AA or Heroin Anonymous, in addition to Centerstone’s programs, as example.

When addicts leave abstinence-based treatment, they have lost their built-up tolerance to opioids. In other words, it would take a smaller amount of heroin or pain pills for them to overdose.

“Time and time again what we have seen is that patients with opioid addictions are unable to stay clean,” Gunawardane said. “Rehab is a temporary measure. It’s part of a long process. Once they leave rehab, what are we doing to help them maintain?”

| Drugs | Oxycontin | Methadone | Suboxone | Vivitrol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pros | Easily treat acute pain | Cost effective addiction treatment | Has a ceiling effect | Any physician could prescribe |

| Cons | Addictive | Requires daily clinic visits | Has a street value | Expensive |

| Common dose | Oral multiple times a day | Oral daily | Oral daily | Injected monthly |

| Cost* | $2.96 - 16.56 | $0.07 - 0.76 | $3.20 - 5.18 | $1272.35 |

| FDA approved | 1995 | 1972 | 2002 | 2010 |

| Overdose reported | ||||

| Contains Opioid | ||||

| Prevents pleasurable high | ||||

| WHO essential medicine |

In March 2015, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared medication-assisted treatment the “most effective form of treatment for opioid use disorders.”

Until they hired Gunawardane last year, Centerstone only had a loose policy on MAT.

“We had something loose before in the sense that we knew that this was a movement across Indiana, but also we were probably going to see this across the nation,” Branam said. “We knew we’d see more people being put on MAT because of the opiate epidemic.”

In deciding how to incorporate medicine into their treatment program — which also involves the support of a recovery coach, group meetings and counseling — Branam said they tried not to reinvent the wheel.

Instead, they looked at what the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration had to say. The answer: coupling medicine with counseling.

“We have a ton of studies on its effectiveness,” Andraka-Christou said. “The people in the treatment centers just aren’t reading them.”

DeLong said Amethyst House would accept patients on Vivitrol, but not methadone and Suboxone.

These two are forms of opiates, the type of drug addicts are addicted to, and that’s the difference, DeLong said.

“When you say it’s a substitute, that’s true in a literal way,” Fishman said. “The criticism is would it somehow be philosophically better if people didn’t have to be on any type of drug as opposed to a drug that is helping them reduce cravings and health risks and live a normal life.”

Most people with opioid addiction do need some sort of MAT, Gunawardane said.

But the drugs themselves aren’t a one-size-fits-all miracle medicine either.

A lot of Gunawardane’s patients want them, but not everyone is ready for them, she said. Some, like Tom, even abused methadone and Suboxone on the street when they couldn’t find their drug of choice.

“Each of these three medications do have their place,” she said. “There are some patients that are very appropriate for one.”

For example, because Suboxone has a street value, it’s not ideal for a patient without a stable living situation.

Kleber was among the first doctors in the nation to prescribe Suboxone.

“I’ve been using it now for the last decade or so,” he said. “Is everyone a potential candidate? Of course not.”

Some people use it to detox, whereas others will sell it, or use it to get high, he said.

“But in my experience those who are using it under supervision are benefiting.”

For other heavily addicted patients, Suboxone wouldn’t be strong enough. Gunawardane tries to get them on methadone.

One big issue: the nearest methadone clinic is in Indianapolis, and the drug needs to be taken daily.

Because of its potential abuse, clinics aren’t allowed to give new patients multiple doses to take home. Her patients often don’t have a driving license or means to make the trip.

And they have to be on time. Driving there from Bloomington, “individuals would have to get up at 3, 4, 5 o’clock to be dosed,” Branam said.

“What we do here, we are very low barrier,” Chris Abert said, gesturing around the Indiana Recovery Alliance office.

Abert, co-founder of the IRA, aims to reduce the health risks associated with illegal drug use, whether that means providing clean needles or referrals to treatment.

The IRA’s silver outreach van is parked outside when he isn’t driving around delivering blankets, food and other supplies. Abert is also trained to teach others to use naloxone, a medication that can reverse an opioid overdose.

“We get people in the door and however long it takes, help them to reach high-barrier services.”

Any MAT is high barrier, Abert said. Access and cost issues prevent many addicts from even considering MAT.

“So if somebody came in and saw positive change as methadone, we would try to hook them up with Indianapolis Treatment Center, which is the closest place,” he said. “The question is, how do you get them up there every day?”

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services lists 289 physicians who have the required waiver to prescribe Suboxone in Indiana.

Five physicians on that list are Bloomington-based. Waitlists are common.

The number prescribing the drug on a regular basis could be even lower, Andraka-Christou, the Ph.D. student analyzing the underuse of MAT, said.

“I think the problem in Indiana or places like that is often you often don’t have enough physicians who are prescribing it or they live too far away,” Kleber said. “Or they don’t know how to use it.”

Suboxone can be an extraordinarily useful medication, Kleber said. But like other medications, it’s not a miracle drug. The standards of medicine-assisted treatment require counseling as well.

“You need therapy too,” Kleber said. “You need a therapist who knows what the hell they are doing.”

But psychiatrists are hesitant, Gunawardane says. With training and a waiver, a doctor can prescribe Suboxone to 30 patients the first year, then 100 after.

“They are very underused,” she said. “I think that physicians have a huge fear that if they start prescribing Suboxone they are going to have a whole bunch of people with addictions lining up at their door.”

In reality, it wouldn’t drastically change a psychiatrist’s patient population because at least 30 percent of patients in their office have addiction issues, Gunawardane said.

Last week at The National Rx Drug Abuse & Heroin Summit, the Obama administration proposed increasing the patient limit for qualified physicians to 200 patients in hopes it would increase access.

Gunawardane is allowed to prescribe to 100 patients, but she said she doesn’t want to. It wouldn’t allow her to give the individual attention to each patient, which she can with the 43 she currently prescribes Suboxone.

“It requires a certain amount of work in terms of following up,” she said. “If you just want to write a ‘scrip a month and send them out the door, that’s doable. If you are going to do actual addictions treatment, it’s a lot more work.”

At Centerstone, Branam keeps a list of the 15 approved outside providers they will also work with.

“It’s been slow to grow,” he said. “It’s not like new people are popping up prescribing MAT.”

But the list itself illustrates one of opponent’s greatest concerns about Suboxone. One of the doctors on the list, Dr. Larry Ley of Noblesville, Indiana, was arrested on felony drug charges two years ago.

Prosecutors claim Ley wrote more than 28,000 prescriptions for Suboxone from 2011 to 2013 and pocketed around $240,000. He also treated approximately 3,675 patients during that time, court documents allege, well over the 100 patient legal limit.

“I was not aware of this news,” Branam said in an email. “Thank you for bringing it to my attention.”

Carol has spent more than $250,000 trying to get her son help for his prescription pill addiction. The IDS agreed to not include her last name because of her son’s association with illegal drug use.

He tried a hospital in Indianapolis and treatment centers in Indiana and Tennessee.

Once, he stayed clean for two years. He relapsed when a pain clinic put him on pain pills for back problems.

Other times, he stayed clean for a few months after treatment. Sometimes, just for days.

When her son was on Suboxone he hated it, Carol said. The doctor would change his dosage on a whim.

He was required to attend 30 minutes of group therapy and 15 minutes of individual therapy with the doctor once a month. It felt like a minimum, Carol said.

He did like the peace of mind that came with injections of Vivitrol, which prevented him from getting high if he tried to use again. But for $1,000 a month, he decided to stop in February after just two injections.

“If you’re like us, you’ll do anything to save your son,” Carol said. “People just can’t afford it. They can’t afford the counseling that goes along with it.”

Medicine and counseling may be the standard of care, but that’s just a slogan to her. “The ideal standard of care is a lot different than reality,” Carol said.

This month, Centerstone began a group of medicine-assisted treatment only patients. In other group therapy, stigma discourages them from talking comfortably about being on medicine, Branam said.

With increased awareness about the different options, he hopes that attitude will change.

“When you start hearing ‘Oh, it’s different than methadone, it’s not like methadone,’” he said. “Suboxone has a ceiling effect. Vivitrol is injected, it doesn’t have a street value. When you start hearing those things, it can change your stance. It’s all about education.”

Tom has been taking Suboxone for eight months now. He takes three strips a day — before breakfast, after lunch, before bed.

“It just frees your mind up, from concentrating constantly on hunting drugs,” he said. “It kills the urges. I told Dr. G she is a godsend.”

He’s moved in with his ailing dad to take care of him and is rebuilding a relationship with his stepdaughter.

The doctors and researchers the IDS spoke with predicted the number of people on MAT will continue growing.

“They walk around and do their jobs and they are doctors and lawyers, teachers and nurses,“ Fishman said. “And nobody knows.”