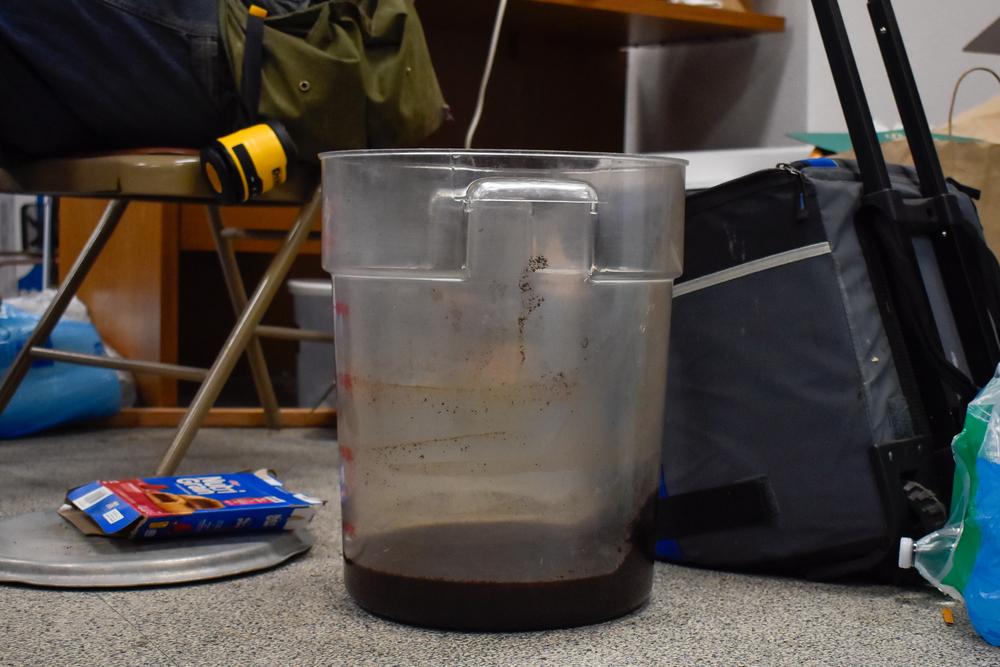

Caleb Hoagland gets in his car and drives the block from his house on Third and Grant streets to the field across from First United Methodist Church. Normally he would walk. But today he needs to transport a 20-liter pitcher of cold brew coffee.

It’s just before 8 a.m. Sunrise is approaching. People around Caleb — some coworkers, some waiting for breakfast to begin — compliment him on his woolen poncho, a cream color dappled with stitches of green and maroon.

“Thanks, it’s alpaca,” he replies. Sack lunches, granola bars, bananas and day-old cookies from Baked sit in separate boxes on a folding table just up a small slope in the field.

Breakfast is open to anyone who wants or needs it, but Bloomington’s homeless community is especially appreciative. There are no barriers to the breakfast. No code to scan or paper to fill out. No name to give or chance for a warrant to be scanned.

“Can I get another one of those?” a man asks after he finishes his first meal, gesturing to the sack meals.

“We’ve gotta save some for the others, maybe later,” a volunteer tells him.

Caleb’s coffee is put to good use. “It’s not warm coffee, but it’s coffee,” Caleb says to a volunteer. The Chobani pumpkin spice creamer next to the station empties within half an hour.

An hour or so into the meal, Caleb pulls out a stack of shiny green bus tickets. He hands them out to anyone who asks, chatting up patrons in a good mood.

He lived in Bloomington for a few scattered periods during his childhood and college. Now, he’s been here for three consecutive years, after he looked to dig his “spurs in.”

Even in such little time, decades-long volunteers say he’s leading the charge for homeless advocacy in the city.

“I'm the poorest I've ever been, but I get to go to bed and like ‘I fed people today, you know, and the day's not even over yet. Who knows, we might do some more good,’” Caleb said.

His official title is outreach director at First Christian Church in Bloomington, but he keeps himself busy. He helps run the Bloomington Severe Weather Emergency Shelter from November through April, when temperatures are below freezing.

Some days he carries clean syringes and hands them out. Some days he just provides companionship.

“Make it their effing home”

On the night of Sept. 26, Caleb saw videos of a group attacking a homeless man outside The Upstairs Pub on Kirkwood Avenue. He saw the video about five minutes after the attacks first happened. He called his pastor and said “I'm going to the church and I'm getting the first aid kit and I'm going down.”

It would soon come out that the main target of the attack was Bobby Ballard, a homeless man who has spent a decade on the streets of Bloomington. Ballard was assaulted to the point of serious bodily injury. Onlookers took videos of the attack and posted them to social media sites, but few jumped in to defend Ballard.

Caleb arrived while tensions were still high. Ballard was missing three teeth but refused to be touched. Caleb gave him antibiotics and took care of the four other homeless people who had been also been targeted during the attacks.

Amber, one of the four, got spat on. Caleb took her and seven other homeless people in the area back to his house to protect them from the high tensions until the bars had their last call at 3:30 a.m.

The group of nine sat around Caleb’s living room eating Kroger Neapolitan ice cream sandwiches, which he purchased on sale for $1.99.

Police arrested four people in connection with the assault. The trials for the alleged attackers haven’t yet happened, but Caleb isn’t optimistic.

“I guarantee you it won't be as permanent as Bobby not having front fucking teeth,” he said.

Caleb makes it a habit to check the crime log on the Monroe County Sheriff's Office’s app every night before bed. He looks for names he knows and recognizes from his advocacy work. If he sees a name he knows, it usually comes with an accompanying trespassing charge.

He soon saw Ballard’s name on the app, two weeks after the publicized attack on Kirkwood, with a battery charge attached. Ballard has since been released and has returned to his typical routine.

Caleb fears this is just the start of heightened tensions between Bloomington and the homeless people living in it. He feels inaction in the city has caused people to dehumanize homeless people. To see them as “other.” And winter, the worst season to be living on the streets, is fast approaching.

“Everything sucks worse during the winter, and it's already sucking worse now,” he said. “I'm really nervous about this…People are gonna die because there's just, there's not enough shelter beds. Period. So even if everyone was at capacity, people are still gonna be out in the cold.”

Caleb thinks the “solution” to homelessness is simple — affordable housing. Everything else that is done to counteract the problem is just a Band-Aid, he said. Caleb also uses the term homeless, not unhoused, when talking about the people he works with.

“I love it when people push back and it's always like, Bloomington liberals that push back and say, ‘Oh well Bloomington's their home.’ Well then, make it their effing home,” Caleb said. “It’s not.”

“Still the weird, queer adopted kid”

Caleb was baptized at First United three years ago.

“I don't look like your mother's Methodist, now do I?” Caleb said while drinking brewed coffee out of a styrofoam Big Gulp gas station cup. When he has time, he makes rounds across Bloomington to pick up whatever businesses are willing to give — usually a free sleeve or two of cups for the free breakfasts or the winter shelter to shut him up.

He’s wearing faded blue overalls with two buttons reading “BIG MAC” keeping up the straps.

“I swear, I'm loud, I'm tattooed, I'm queer,” Caleb said. “I’m all of this and unapologetic about all of it.”

He’s got tattoos on every limb, some professionally done and some he did himself with stick-and-poke techniques.

Caleb was born to a 17-year-old mother in 1986. His great-grandparents raised him until his dad adopted him at age 7. That’s when he first moved to Bloomington.

His parents kicked him out when he was 16.

“I was a handful, for sure,” Caleb said. “But does any kid deserve to get kicked out? I don't know.”

He spent the next two years finishing high school two hours away from Bloomington in Plymouth, Indiana. He chose Plymouth High School because of its speech and debate program.

Then he graduated. He wasn’t ready for college, so he joined the army.

“I thought that this was like, would make it so I wasn't the weird queer adopted kid and we'd have something in common,” he said. “And I was still the weird queer adopted kid, I just now have a traumatic brain injury and PTSD.”

Caleb served two tours in Iraq from 2004-09.

The U.S. military’s official policy for LGBTQ+ members was “Don’t ask, don’t tell” during his service. Caleb was out anyway.

He served in the infantry and quickly rose in rank.

“I'm not gonna lead men based on a lie. And no one cared. It was not an issue anywhere in my unit,” Caleb said. “They cared that when we got shot at, I shot back; I got casualties out and I could do first aid. That's what mattered.”

It was hard for Caleb to adjust back to life outside a warzone. After returning for the last time from a 15-month deployment in 2009, a grocery trip for his mom proved too much.

“I walked and I turned down the aisle and I saw all the bread. And my brain couldn't comprehend what was happening,” Caleb said. “I was like, ‘That's so much bread.’”

Then a box hit the floor and Caleb hit the ground. He was back in Iraq. He started crying in the middle of Kroger.

He found ways to cope. Caleb got in a routine of getting his groceries at 2 or 3 a.m. at Kroger. He would wear headphones and listen to gangster rap — lots of Freddie Gibbs, especially “Str8 Killa No Filla.”

“I was young, I was poor, a bunch of my friends had been getting shot,” Caleb said. “I could relate.”

His nocturnal shopping routine lasted about four years — as long as his original enlistment contract.

COVID-19 flipped a switch for him. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs — which provides the free health care he’s entitled to — expanded eligibility for non-VA mental health treatments.

His PTSD hadn’t improved. He had just taken a new job as a wine expert, but between the pandemic and downsizing, he knew he was going to get laid off. He quit instead and booked 10 months of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, a treatment known for its ability to effectively treat severe trauma, including PTSD.

It’s been four years since the treatment, and Caleb still feels the positive effects of it, though he’s likely due for more soon.

“There's still rough days,” Caleb said. “That's where I just give myself grace and a bottle of whiskey and cry a lot.”

“Sometimes it's easier just to get called a motherfucker.”

The sun is up at Sunday breakfast. About 20 people who have already received breakfast eat, sitting on the sidewalk against the chain-link fence or across the street against First United’s walls.

One woman starts to enter the gate. She’s accompanied by a black and white medium-sized mutt named Sophie. Caleb tells her animals can’t come inside the fence per the church’s rules.

“That dog’s my life,” Red, the woman, says to Caleb. She leaves down the block, dog in tow, out of sight.

Caleb doesn’t dislike dogs. He knows Red and has bought her dog, Sophie, food many times or held her leash on occasions like these. But First United asked that no dogs come onto the field because of potential parasites they could carry.

Caleb knows Red’s having a hard day. She probably just woke up. She’s one of the many homeless women who choose to sleep on the street rather than in a shelter.

“You have to think of it from a de-escalation standpoint. So, just let her go off and storm off,” Caleb said. “You have to kind of think about those things when you're trying to de-escalate or solve situations. So sometimes it's easier just to get called a motherfucker.”

He’ll find her later and give her food. He’s used to it; people lash out at him all the time. He’s been called a lot of words.

Motherfucker.

Bastard.

Dick.

But he said nobody has ever called him a “faggot.”

“They all know I'm queer,” Caleb said. “But that's never been an issue.”

It’s not personal and he knows it. Being sworn at has somehow always been an occupational hazard for Caleb.

“Between my mother and the United States Army, I'm the Michael Phelps of getting yelled at,” Caleb said.

“A chaos goblin, trauma junkie”

Caleb returned to Bloomington for Indiana University. He earned free college after enlisting and wanted to study political science.

“I wanted to focus on international political economies, so I went from Iraq to a lecture hall of 300 18-year-olds talking about Iraq,” Caleb said. “And it was brutal.”

He carried a gun with him at all times. He’d wake up and do perimeter checks.

“I was a mess,” Caleb said. “I was like Lieutenant fucking Dan.”

But today, Caleb has managed to find a silver lining with his PTSD — nothing phases him at all.

“For a long time people would be like, ‘How's your day going?’ I'd be like, ‘No one shot at me, must be a good day,’” he said.

It makes him good at his job. The shelter only had one drug-related emergency last year and he was able to get the person the help she needed.

Caleb has become an expert at dealing with other people’s crises. The tattoos on his right calf are proof. Most of them weren’t done by trained artists; they were given by his friends or others in crisis.

It started two years ago, when Caleb’s now-good friend Katie was having a mental health crisis.

“I could not cheer this person up, I could not get through to them,” Caleb said.

Then he had an idea.

“How about you tattoo me?” he asked.

Five minutes later, Katie was holding a needle. Soon after, Caleb’s leg was adorned with a smiley-face tattoo.

“I'm a chaos goblin, trauma junkie,” Caleb said. “This is where I'm comfortable in a crisis, but other people aren't.”

Caleb thinks the real harm in any crisis is the lack of power and control the person feels.

“So you just say, ‘Hey, here's a tattoo needle. Go at it. You're putting something on me that's gonna be on me until the day I die,’” he said. “And it just stops the crisis right there.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correct Caleb’s mother’s age.

Like what you're reading?

Support independent, award-winning student journalism.

Donate.