‘Catastrophic’: The difficulty of addressing severe car crashes in Bloomington

City transportation employees have limited resources and face political challenges.

IDS file photo by Alex Deryn

Bloomington police cars and fire trucks surround a car crash site Aug. 11, 2020. Fatal crashes jumped in 2020 while total crashes fell, due to increased speeding during COVID-19 lockdowns.

A few weeks after Hank Duncan began his job as the Bloomington Bicycle and Pedestrian Coordinator on Oct. 31, 2022, he received an upsetting report at work. Just 200 feet from his house, there had been a car crash involving a pedestrian.

“It was catastrophic,” Duncan said. “Just thinking about the people who live there and the lack of proper infrastructure to protect those people, it's sickening. Seeing that every day on my way home, my way to work, I just think about that. It's truly awful.”

The crash was particularly relevant to Duncan, who works with the Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Commission to improve pedestrian infrastructure in the city. But Duncan said traffic safety efforts are inadequate to properly address crashes like the one that happened right by his house, both in Bloomington and across the country.

“It's such a big problem,” Duncan said. “There are people working on it, but it's not being worked on quickly enough.”

Advertisement

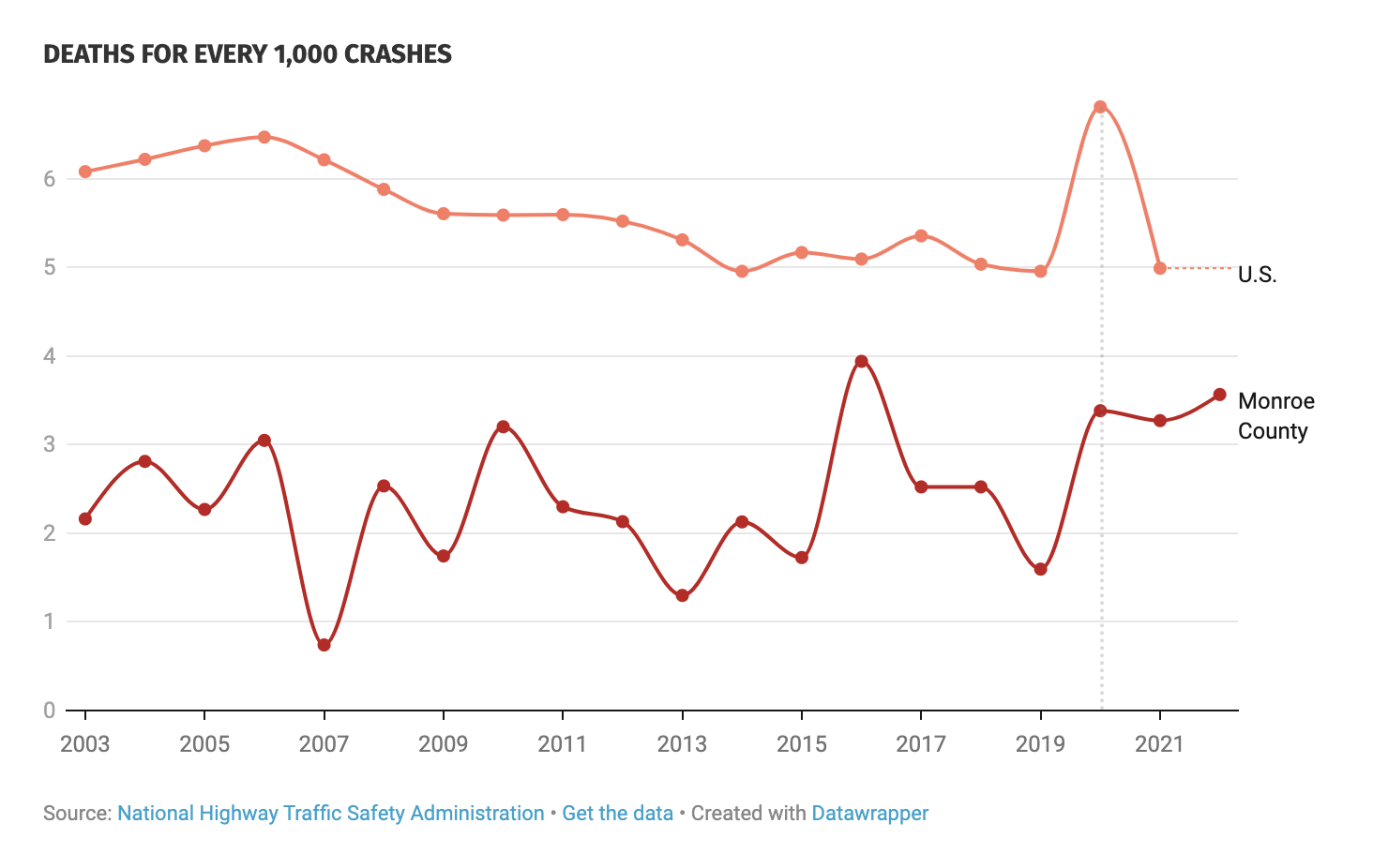

Severe car crashes, and especially those involving pedestrians or cyclists, have recently risen nationally. In 2020, crash deaths spiked even as total crashes dropped due to COVID-19 lockdowns. This trend has been attributed to more speeding that year, since roads were less crowded.

But experts are increasingly concerned about broader traffic infrastructure and car-focused culture in the United States. Crash deaths increased again in 2021 and 2022, and pedestrian deaths hit a 40-year high in 2021.

In 2020, fatal crashes rose even as total crashes dropped

Percent change from 2007

U.S. citizens in 2019 were more than twice as likely to die from car crashes compared with two dozen other high-income countries, according to research from the CDC.

“The U.S. could save more than 20,500 lives and about $280.5 million in annual medical costs (in 2019 USD) if we could reduce the population-based crash death rate to match the average rate of 28 other high-income countries,” the CDC report noted.

Car crashes in Monroe County follow these troubling national trends, according to a new analysis by the Indiana Daily Student of all available local crash data from 2003 to 2022.

Fatal crashes in Monroe County generally follow recent national trends

Number of fatalities per every 1,000 crashes

This school year alone in Bloomington, at least two students have died in collisions between cars and scooters, along with at least three more people and multiple others who have suffered severe injuries from crashes. At least two cars have also crashed into buildings around Bloomington.

Bloomington has a wealth of passionate transportation advocates and dedicated city employees who told the IDS they are aware of and concerned by recent spikes in pedestrian crashes. But many of them, like Duncan, said things aren’t happening quickly enough as they deal with limited resources, funding issues and resident opposition to traffic safety projects.

“What do we prioritize?” Duncan said. “We only have enough funding for certain projects, so we can't fix everything all at once, and that hurts.”

Addressing severe crashes in Bloomington

Beth Rosenbarger, assistant director of the Bloomington Planning and Transportation Department, said she hopes the city will soon adopt a Vision Zero approach, which is a strategy to eliminate severe car crashes that cause fatalities or serious injuries.

Advertisement

“A lot of us on staff are very familiar with Vision Zero goals,” Rosenbarger said. “We want that as a goal. The question is, how do we set ourselves up to get there?”

Rosenbarger said there are several approaches known to reduce harm from vehicle collisions that could be implemented in Bloomington. One is reducing speed, the largest predictor of whether a crash is fatal.

We want (Vision Zero) as a goal. The question is, how do we set ourselves up to get there?

— Beth Rosenbarger

“Anywhere from 15 MPH to 25 MPH has great safety gains compared to 30, 35, 40,” she said.

Reducing speeding goes beyond changing posted speed limits, Rosenbarger said. Instead, changing how roads are designed, such as by making them narrower by adding a protected bike lane, would discourage speeding more effectively.

“We can't control individuals, sometimes the person is going to speed in a situation that doesn't even make sense,” she said. “What we can do is work to design streets where the overwhelming majority of the time, people are driving at lower speeds and that results in greater probability of safety.”

The Bloomington Traffic Calming and Greenways Program follows this approach by implementing traffic calming infrastructure intended to slow drivers and encourage pedestrians and cyclists to travel along neighborhood greenways. This involves changing traffic infrastructure by narrowing roads or adding speed bumps or median barriers.

Zuzanna Kukawska | IDS

A bicyclist is seen on the Seventh and Longview Greenway May 5, 2023, crossing the intersection of Seventh Street and Indiana Avenue. This is one of the neighborhood greenways implemented by the city, meant to slow vehicle speeds and increase pedestrian and cyclist traffic.

Zuzanna Kukawska | IDS

A lime scooter and campus shuttle share the street May 5, 2023, on the Seventh and Longview Greenway. Some new neighborhood greenways projects have resulted in pushback from residents.

Zuzanna Kukawska | IDS

A lime scooter and campus shuttle share the street May 5, 2023, on the Seventh and Longview Greenway. Some new neighborhood greenways projects have resulted in pushback from residents.

Rosenbarger also said Vision Zero requires a proactive approach, not just choosing new projects as a reaction to fatal crashes that already happened. This can involve identifying problematic intersections and planning infrastructure changes before crashes occur.

But Rosenbarger added that proactive projects can receive the most pushback from residents, as some have trouble understanding the rationale behind changing an intersection, because they don’t have the urban planning or engineering expertise of the city staff.

Recently, a traffic calming project received pushback from residents in the Elm Heights neighborhood, one of the wealthiest areas in Bloomington.

“The people who push back on it kind of say they don't see the need for the project,” Rosenbarger said. “I think that's hard to wrap your mind around a proactive versus a reactive project.”

Rosenbarger said she is concerned about recent conflicts in the city council, mostly involving projects in the Elm Heights neighborhood, which are calling pre-approved traffic calming projects back into question.

Advertisement

“There is a challenging conversation about how much and how often we're asking people to show up, to keep answering the same questions and to keep asking for the same things,” Rosenbarger said.

Especially as residents from poorer neighborhoods are less likely to have the time or resources to attend public meetings and might not even know about those opportunities to have their voices heard, Rosenbarger said it becomes a large equity issue.

The challenge of making transportation equitable

In 2020, a volunteer analyzed public sidewalk data and found inequities in who was getting new sidewalks, single handedly changing the process city council uses to distribute sidewalk funding.

Mark Stosberg, the volunteer and then-president of the Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Commission, found that poorer areas were objectively in need of better sidewalks, including some where residents were walking on dirt next to a road to reach a bus stop. But these areas had not received funding from the existing Sidewalk Committee.

Stosberg said these disparities resulted from multiple factors including the number of complaints filed to decide where to allocate resources. He said he also analyzed the city’s complaint system and noticed stark differences in complaints coming from different neighborhoods.

Advertisement

He said some neighborhoods had an organized approach to get many people to complain about even small issues, while generally poorer neighborhoods rarely ever complained at public meetings, even if they had worse existing infrastructure.

“I just think either they didn't have time because they were busy working, or they just didn't think the system was built to work for them,” Stosberg said. “Why complain if it wouldn't make a difference?”

In the year after his report came out, Stosberg worked with city employees in the Planning and Transportation Department to provide more analysis and technical help to create a more evidence-based approach to funding sidewalks that kept socioeconomic factors in mind.

“Since then, the city staff resolved to use a more objective method,” Stosberg said.

Why complain if it wouldn't make a difference?

— Mark Stosberg

Rosenbarger, the associate director of the department, agreed that complaint-based urban planning often falls short of delivering equitable solutions for communities.

“People with children, people with jobs that aren't nine to five, people who are serving caretaking responsibilities, that is a lot of time out of your schedule,” Rosenbarger said. “There’s a large equity issue in terms of people's time and ability to participate.”

But Rosenbarger also pointed out that while data is an important tool to identify inequities, it’s only part of the story and can leave out important context.

For example, she said county car crash data can be useful to identify areas that are unsafe for cyclists by identifying intersections where past crashes happened. But she added that roads with no reported crashes could still need bike infrastructure, and they might not show up in the data because cyclists already avoid them due to feeling unsafe.

Rosenbarger said the city’s Transportation Plan serves as a guideline for which transportation projects to prioritize. According to the plan, city employees used technical metrics and feedback from residents and public officials collected over a series of public meetings to determine which projects to include, and the final version was approved by the city council in 2019.

Zuzanna Kukawska | IDS

The Elm Heights Neighborhood is seen May 5, 2023. The residents of Elm Heights, one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Bloomington, are often more likely to complain at public meetings than those from other neighborhoods, according to traffic officials and advocates.

But recently, the city council has taken unprecedented steps to gain control over specific traffic projects, proposing an ordinance which would require another round of city council approval on neighborhood greenways projects they already OKed in the 2019 plan. The ordinance is set to be voted on in the next council meeting on May 10. The projects receiving pushback have mostly involved the Elm Heights neighborhood.

Greg Alexander is a member of the Traffic Commission, an advisory group that hears complaints from residents and makes recommendations to the city council and Bloomington city employees on traffic safety. Alexander said he has been frustrated by the complaint-based approach of the council, particularly with the Elm Heights neighborhood.

Advertisement

Alexander said he thinks residents who complain about proposed traffic safety projects lack respect for experts in the city engineering and planning departments, which contributes to more pushback on the proposed projects.

For example, Alexander cited a dispute from January about a stop sign an Elm Heights resident wanted installed. In a break from typical procedure, the resident, Stephanie Hatton, was given unlimited time at a city council meeting to present on the stop sign request, which was ultimately installed against initial recommendations from the city Engineering Department and the Traffic Commission.

Zuzanna Kukawska | IDS

A new stop sign is seen May 5, 2023, at the intersection of Maxwel Lane and Sheridan Drive. The stop sign was pushed through by residents of the Elm Heights neighborhood in an unorthodox process that went against recommendations from the city Traffic Commission and Engineering Department.

Councilmember Dave Rollo, who represents the Elm Heights neighborhood, has called for Alexander’s removal from the Traffic Commission multiple times, taking issue with tweets that Rollo said showed Alexander was biased against the Elm Heights neighborhood. Alexander remains on the Traffic Commission.

Andrew Cibor, Bloomington city engineer, was involved in the stop sign dispute. Cibor told the IDS that as a city official, he must balance both providing engineering expertise and fielding community concerns.

“If somebody has a question or wants to meet or wants to share a concern, they have every right to do so, and they should be treated respectfully,” Cibor said.

But he also said that dealing with complaints “also limits our ability as a professional staff to be more proactive.”

The role of county crash data in planning

Multiple city employees told the IDS they frequently refer to county crash data as part of their jobs in the Planning and Transportation Department. Despite its limitations, the crash data plays an important role in providing insights on transportation issues in the area, they said.

The public crash data has many inconsistencies and is difficult to work with. To help Bloomington residents view insights from the crash data and explore specific transportation issues in their neighborhoods, the IDS has published an analysis and interactive map of all 20 years of available data.

The public data posted on the Bloomington Open Data site does not include information about which crashes involved pedestrians or cyclists, even though pedestrian fatalities are one of the largest concerns of transportation advocates nationally. This is because the public datasets are compiled at the state level, city officials said, and don’t automatically include fields showing whether pedestrians or cyclists were involved.

The difficulty of extracting pedestrian and cyclist data from the state’s crash reporting system has frustrated city officials, including transportation technician Mike Stewart, who described their system as a black box. To make this data public, the IDS worked with city employees, including Stewart, to add this information to the datasets and map.

The IDS also put together a data dictionary of all the crash data, which includes details on fields that are unclear or might have caveats that aren’t explained in the public data website.

The code used to clean the public data, as well as source data and cleaned data files files for years 2003 to 2022 and a master file that combines all years, are available on a public IDS Github repository.

Like what you're reading?

Support independent, award-winning student journalism.

Donate.