As Charlotte Zietlow lay in hospice care, in the final days of her life, a nurse asked if there was anything she could do for her.

The nurse told Rebecca, Charlotte’s daughter, that her mother answered in a rasp:

“Absentee ballot.”

It was not long before Election Day, 2025. Charlotte’s party, the Democrats, won big in high-profile races across the country — though there weren’t any in Bloomington. People told her about the results even when she was no longer conscious. Rebecca believes she understood.

“I think that’s what many of us think: she was waiting for that,” Rebecca said.

Charlotte died the next day, Nov. 5. She was 91. The family hopes to have a celebration of life in April. One consideration is finding a place to fit everyone who’d attend.

Charlotte’s been named a community éminence grise, the grand dame of Monroe County politics and doyenne of Bloomington Democrats. Her political career started over 65 years ago. And in her last weeks — on her death bed — her commitment to politics and community never ceased.

The Indiana Daily Student, intending to profile Charlotte, spoke to her twice in October at her home. The following is a portrait of the Monroe County matriarch whose name is etched into Bloomington history.

•••

Born in 1934 in Milwaukee, Charlotte’s path to politics wasn’t direct; her Minnesota high school didn't even teach history, she said.

She’d get her political jump in Ann Arbor while at the University of Michigan, where she received her master’s degree in French and German literature and doctoral degree in linguistics. After connecting with what then-presidential candidate John F. Kennedy had to say, she started door knocking for him.

Many who answered said they wouldn’t vote for a Catholic. When Charlotte told them her father, a Lutheran minister, would vote for Kennedy, she was able to change some votes.

“I thought, ‘I have to keep going, and I have to keep talking,’” she said, “because not talking means nothing happens.”

It was in high school she met her husband, Paul. They didn’t date before they went to separate colleges, but the pair stayed in touch. Eventually, Paul asked Charlotte to visit him at Yale.

“I knew, and he knew, that we would be married and live happily ever after, just like that,” Charlotte said.

They were married 58 years until Paul’s death in 2015. Rebecca said Charlotte considered marrying Paul her greatest accomplishment.

They moved to Bloomington in 1964 when Paul was hired as an English professor at Indiana University. Charlotte, Paul and their children, Rebecca and Nathan, then lived in Czechoslovakia for about a year while Paul taught at a university there.

Charlotte saw the Czechoslovakian government restrict free speech and dissent. When she returned to Bloomington, she saw a city council openly ignoring the public at meetings. With those experiences in mind, she ran for Bloomington City Council in 1971. Charlotte and a cohort of other Democrats won, flipping Bloomington government from a red majority to a blue one. She was the first woman to become City Council president.

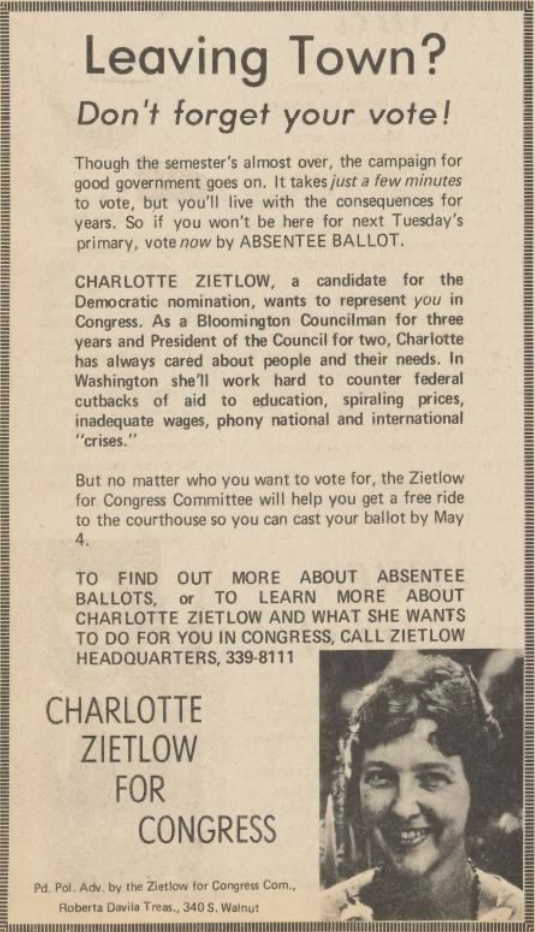

Page from IDS Archives

She embarked on a number of other political campaigns. Her U.S. House of Representatives runs in the 70s and Bloomington mayoral bids in 1975, 1987 and 1995 were unsuccessful, but she became the first woman to join the Monroe County Board of Commissioners in 1980.

The Zietlows had two newspapers delivered to their home, Nathan said, and he’d often see his mom’s name in the stories. She was always busy. Politics was everywhere.

“That was the main dinner conversation, probably, you know, 95% of the time,” Nathan said.

Courtesy of Monroe County History Center

She made some of her most visible marks on the community while an elected official. She helped prevent the demolition of the Monroe County Courthouse. Amid a lawsuit over the county jail’s conditions, she spearheaded the creation of the current center now bearing her name. Alongside friend and fellow politician Marilyn Schultz, Charlotte opened the culinary ware store now called Goods for Cooks downtown.

She embedded herself in all corners of Bloomington’s community even beyond her time in office. United Way of Monroe County executive director. IU adjunct professor. Administrative staff positions at Planned Parenthood and Middle Way House. Member of boards, commissions, committees and councils. She wrote two books of her own, chronicling her political career. She was particularly proud of her years of service as Indiana State University trustee.

Her grandchildren were especially important to her, Nathan said. Charlotte’s resume is seven pages long. It lists each of her close family members by name, right below her awards.

•••

Charlotte was only at Bell Trace Senior Living Community for a few weeks, but the hat rack outside her door was a clear sign of her tenancy.

Yellow, tan, black and blue hats. A purple one sat above them all. That was Charlotte’s favorite color.

Inside the apartment, on an early October day, the then-90-year-old sat in a chair in her living room. She was dressed in her favorite color. A purple gown. Purple shawl. Purple glasses. Her walker was purple. So was her purse. There was even a purple bruise under her right eye. The color of royalty.

She’s busy this week. Why?

“Partly, I’m trying to stir some trouble up,” she said.

Charlotte was doing all she could to prevent the construction of a new Monroe County jail.

County officials were in the process of moving the jail and circuit court to a site between Bloomington and Ellettsville. It came after years of delays and over a decade of complaints about the jail’s conditions beginning with an American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana lawsuit.

With renewed pressure from the ACLU to press forward with construction on one end and unclear finances on the other, it was uncertain if it’d proceed as planned. Charlotte hoped it wouldn’t.

Her work on creating the Charlotte Zietlow Justice Center was a complicated process, she said, that shaped her perspective on what a jail should do: rehabilitate people.

The facility bearing her name is not serving its purposes, Charlotte said. But the proposed 400-to-500-bed facility with a price tag north of $220 million wasn’t the answer to her. She wanted to see the money spent in other ways, including on counseling, mental health services and work programs.

“We’re not doing anything to move people forward, and that’s what we should be thinking about,” Charlotte said.

Up through her time at Bell Trace, any given week was full for her. There was hardly an empty day in her calendar. “NAACP meeting — 6:30 Zoom.” “Rally against Racism 4:45.” Speech therapy without a set time. Meetings with Barb, Marty, Norm, Sandi.

Jack Forrest

The flurry of phone calls, visits and meetings continued. Four people had signed in downstairs to meet her Oct. 2 alone.

But much of her time and energy went toward the jail. She spoke to Jennifer Crossley, County Council president, in the weeks before the council would vote on whether to fund the property purchase for the jail. Jennifer sought her insight. Charlotte wanted to be involved.

“‘Tell me how I can help,’” she’d tell Jennifer.

•••

In a booth at the westside Bucceto’s Pizza Pasta, Dee Owens placed a folder labeled “Charlotte” in faded cursive letters on the table.

“I was lucky enough to have two mothers: a mother and a stepmother,” Dee said later. “And actually, I got an adopted mother, too. And that was Charlotte.”

The folder held a tidy, small stack of papers. One, an IDS clipping about Charlotte’s 1978 congressional bid, deemed her “a straightforward and articulate woman.” Another, a campaign flyer, read, “A woman’s place is in the House of Representatives.”

Dee knew Charlotte since 1974, her first run at Congress. Dee was a student at Indiana State University at the time, president of the school’s College Democrats. Charlotte lost that Democratic primary but won it four years later, becoming the party’s candidate for the 7th District in 1978.

It was then that Dee worked on her campaign, making phone calls alongside 10-15 other students. Charlotte endured sexist remarks — the “PhD housewife,” people’d call her — and ultimately lost the general election. But in Charlotte, Dee found inspiration.

“I just remember thinking that — if this lady can do that, so could I,” Dee said.

Around 20 years later, Regina Moore, another friend of Charlotte’s, became Bloomington’s city clerk. After she won re-election in 2003, she realized there wouldn’t be a single woman on the city council — for the first time since Charlotte had won her race.

Regina and Susan Sandberg, who’d lost a council bid that year, began reaching out to progressive Democratic women to do something. Dee, now in Bloomington, was one of them. Charlotte was a given. Regina, Susan and others formed the Democratic Women’s Caucus, a political action committee to recruit and fundraise for Democratic women in local office.

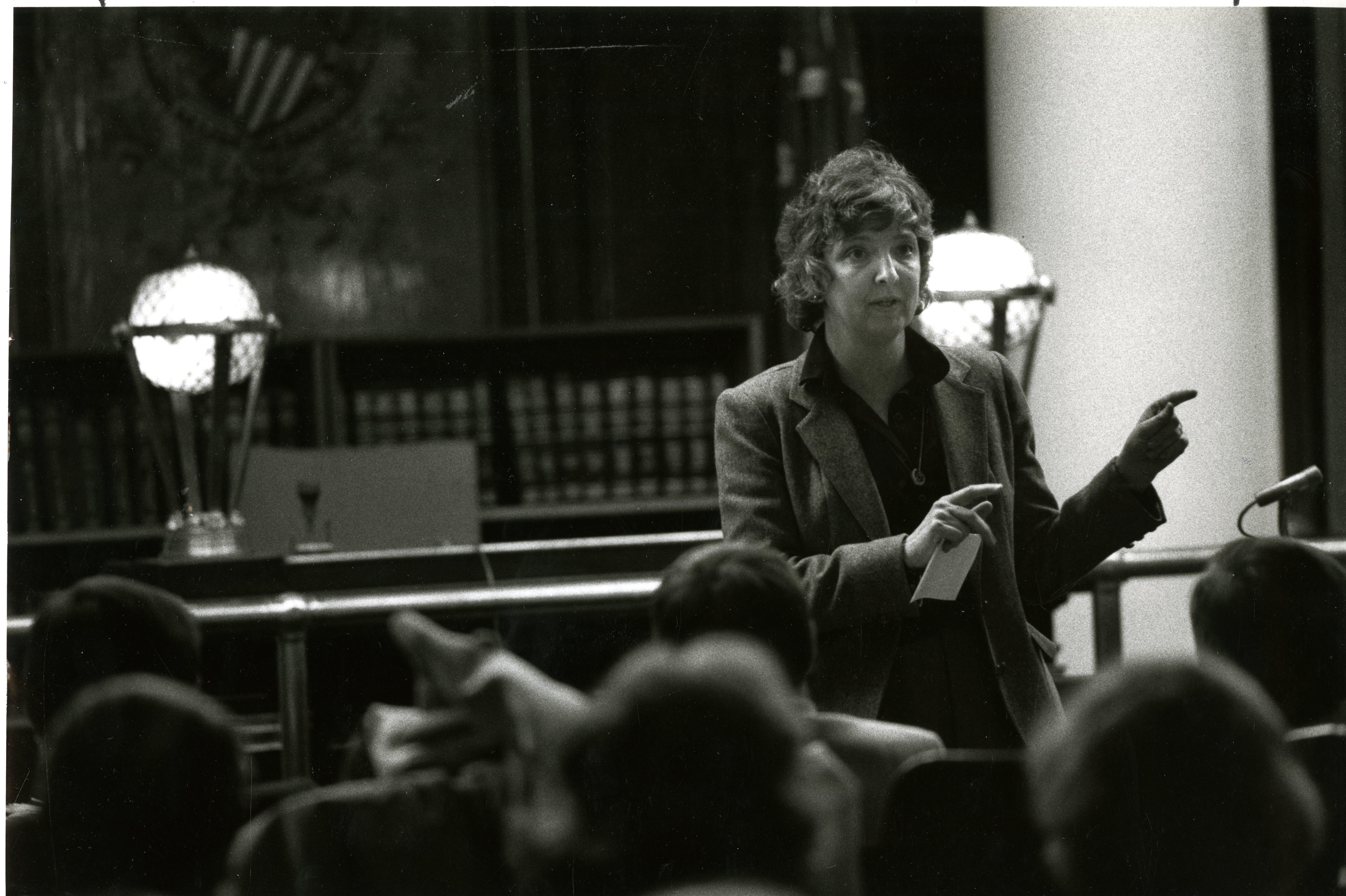

IDS file photo

Charlotte went to every single meeting. She’d call Dee, get lunch with Regina. She’d have book clubs, cook dinners. Politics was a constant in everything.

“That’s all there is,” Dee said.

Dee and Regina went to a Monroe County Democratic Party dinner weeks after Charlotte’s death. Dee couldn’t help but look around for Charlotte, expecting her to be there.

Regina was struck by the number of women up and down the program. Speakers, honorees, party leadership. She thought, for a moment, the work of the Democratic Women’s Caucus could be done.

“No, we’re not done, because obviously things will resume back to the way they were,” Regina said. “But I think that people are now, without even thinking about it, looking at women in a different way.”

The women at the dinner were standing on the shoulders of the women in politics that came before, Regina said. Charlotte was one of them.

•••

It was a different October day at Charlotte’s apartment. She’d been out at doctors’ offices. She was tired, deciding to skip an evening dinner event. But there was something she wouldn’t skip.

One of Charlotte’s caregivers helped her from the living room into the bedroom. Campaign posters for John F. Kennedy leaned against the wall.

She sat on a cushion in a chair in front of a computer, adjusting the height of the chair and desk until she could best see the screen: a video meeting to plan a panel opposing the new jail.

She was tired, but she spoke her mind. She was against having breakout sessions at the event. She wanted the audience to leave with a better understanding of what’s wrong with the jail project. She’d handle reaching out to the media, she said, as well as the Democratic Women’s Caucus. She raised her hand when she had something to say.

People listened when she talked.

Courtesy of Monroe County History Center

They listened when she came by her old store, current Goods for Cooks co-owner Sam Eibling said. Around three years ago, Charlotte came into the store looking for a five-holed zester for lemons from a specific vendor. The store wasn’t carrying it, so she requested they order it. They did.

“You order what Charlotte tells you to order,” Sam said.

She maintained the same respect in her old stomping grounds of local government, often acting as a sounding board or resource.

Steve Volan was a city councilmember when Charlotte invited him to lunch around 15 years ago. That began their friendship. She’d “summon” him to hear about the issues of the day. He’d seek her advice on another. They’d go out for dinner at Samira Restaurant or Sushi Bar. He edited her second book.

He said he was just one of many who considered her a friend or at least respected her — “and that includes no small number of Republicans.” She was like the Herman B Wells of the city, Steve said.

That community is what Charlotte loved so much about Bloomington, Rebecca said. After Paul’s death, she tried to get her mother to move closer to her. Charlotte wouldn’t leave.

Courtesy Photo

“I used to tease her and call her the ‘queen of Bloomington,’” Rebecca said.

It was openness — from speaking to anti-Catholic voters to earning respect across the aisle — that Charlotte said she wanted to be defined by.

“I’d like to be thought of as somebody who’s fair, open-minded and active and willing to go to bat for people as well as ideas,” Charlotte said. “That I’m strong and don’t shy away from controversy, but that I try to smooth it.”

•••

Charlotte was hospitalized after her physical condition worsened. She didn’t get to speak at the panel against the jail or attend another protest she’d planned to. Her wit stayed with her.

Just over a week before she died, the council took the jail site funding to a vote during an hours-long meeting with numerous public comments. Among the speakers was former Bloomington Mayor John Hamilton. Charlotte, as she put it, did not get along with him.

He took to public comment virtually to read a statement he and Charlotte had written together opposing the jail. He asked attendees to hear it in her voice.

“We two, John and Charlotte, haven’t always agreed during our combined nearly a century of activism and experience in local and state politics, but we do now,” the statement read in part.

The council went on to vote unanimously against funding the jail purchase — a victory for Charlotte and her fight.

Working with someone she’d butted heads with was one of Charlotte’s great strengths, Rebecca said. She didn’t know her mom had written the letter, but when she read about it in the obituaries, she loved it.

Her mom had a motto: “Nothing doesn’t matter.” That’s one of the legacies Rebecca hopes Charlotte leaves behind.

Every human interaction matters.

Like what you're reading?

Support independent, award-winning student journalism.

Donate.